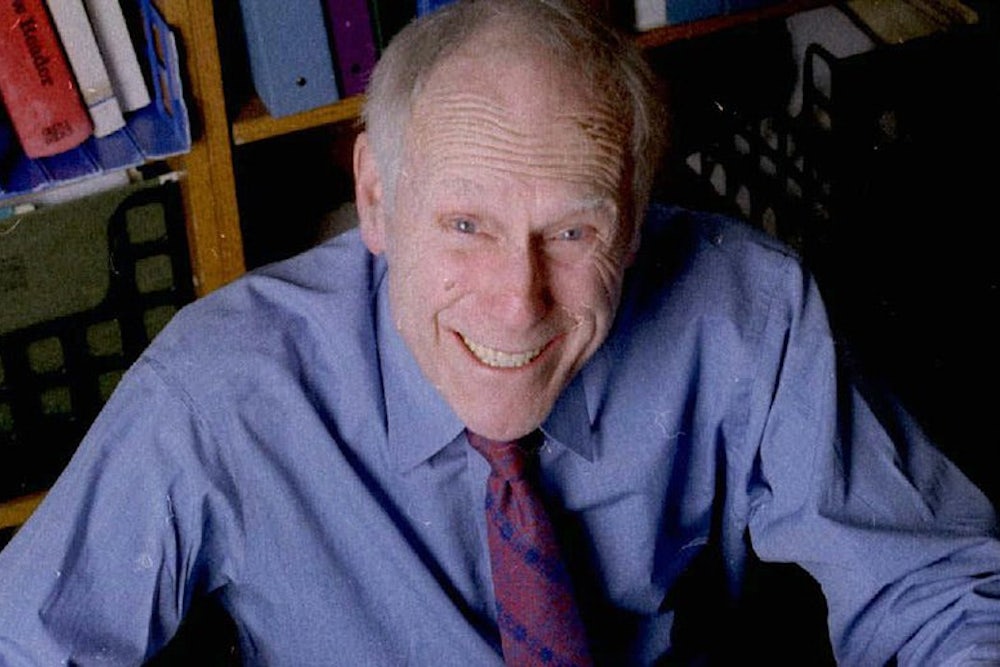

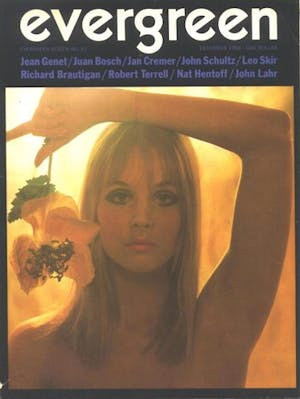

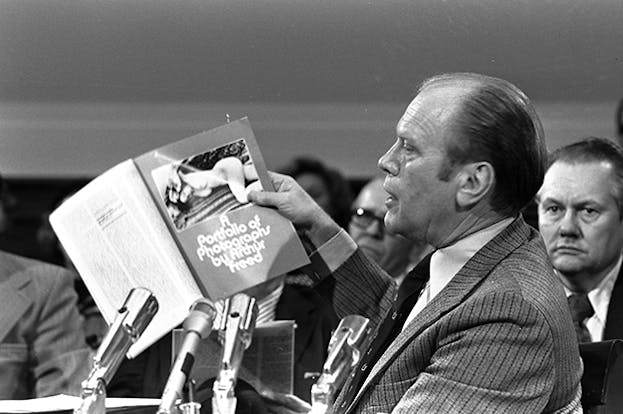

In 2012, when Barnet Lee Rosset, Jr. died, he left behind many nicknames: The Old Smut Peddler, The Last Maverick of Publishing, and The New York Anarchist, among others. To his friends he was Barney; to everyone else, he was the longtime publisher of Grove Press and later, the editor of the politically charged, “sex-positive” quarterly, the Evergreen Review. He drank rum and cokes exclusively and frequently. He fought obscenity charges in the United States Supreme Court and won, single-handedly bringing the words fuck and cunt to American letters.

“Barney was in publishing, but he was never part of the publishing establishment. He was south of 14th Street, he was in the Lower East Side, a fixture of the underground, a loose cannon,” Astrid Meyers Rosset, Barney’s fifth (and final) wife explained to me over tea one afternoon. I had reached out to her through a series of mutual friends, hoping she could tell me more about Barney, and about his final piece of work. She was kind, uninhibited, and she greeted me as if she’d met me before. We talked for three hours.

“Rosset wasn’t a conventional publisher, but he was respected in the industry,” she said. “No one wanted to do what he was doing but they wanted it done.” What Rosset was doing, of course, was taking the American government to court. Barney spent his career ruffling the feathers of conservative thought—he was known for his work, nurturing controversial new writers. But what is left out of Rosset’s obituaries is the mural he spent the last years of his life working on, a single painting—12 feet high, 22 feet long—that spans the entire length of his fourth-floor living room wall.

It’s brightly colored with acrylic paint, mostly blue, with ponds of gold and specks of red. In February of this year, Meyers Rosset opened the loft up to to the public for an evening to display Rosset’s wall. Staples in the literary scene, artists, and old friends of Rosset’s came to see the mural. If you get close enough, you can see the layers of paint, the toy soldiers bought nearby on Astor Place, glued to the wall, and cufflinks embedded in the paint as eyes. Rosset had a box filled with different things—flattened soup cans, pictures he had taken while in China with the photographic unit of the Army in World War II—he’d intended to put on the wall. He died before he could add them.

The 4th Avenue building where Rosset’s painting lives, will, like most turn-of-the-century East Village apartments, be demolished—and, when it goes, we’re liable to forget Rosset’s legacy. The question now becomes: How can we save the wall? Or rather: Why should we?

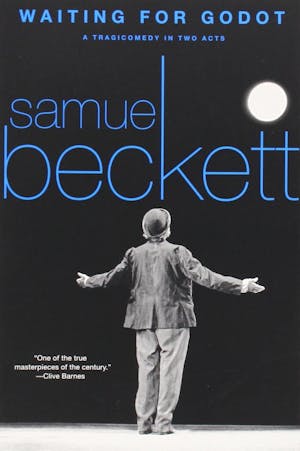

John Oakes, co-publisher of OR Books and a onetime employee at Grove Press, put Rosset’s impact in context in an email exchange I shared with him earlier this year. “He's influenced everyone's taste in contemporary fiction, whether they know it or not.” Oakes met Rosset in 1979, while doing his undergraduate thesis on Samuel Beckett. He corresponded with Beckett, through Rosset, his messenger, until Beckett’s death. Having known and worked with Rosset for nearly two decades, Oakes remembers him kindly. When asked if he credited Rosset with paving the way for the future of publishing, he responds: "That is the least of his contributions: he reshaped American culture."

Rosset wasn’t the first provocative literary publisher of the twentieth century—that honor belongs to either James Laughlin at New Directions or to Jack Kahane at Paris Obelisk Press—but he was inarguably the bravest. (When a book came along that might have caused New Directions legal trouble, Laughlin would reportedly say “Let Barney do it.”) Barney was on a mission to change American sensibility, to challenge ideas about art, to preserve democracy, to push beyond literary puritanism. He understood the need for controversy, and he knew how to generate it.

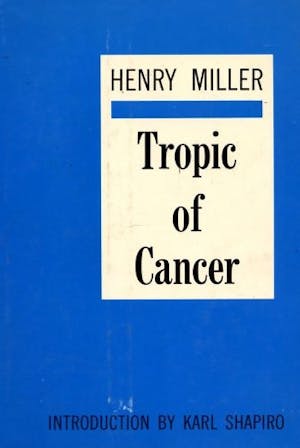

The titles Grove Press released are now synonymous with provocation and scandal—Waiting for Godot, Naked Lunch, and A Confederacy of Dunces among them—and the authors Rosset published were no less eminent, counting D. H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Samuel Beckett, William S. Burroughs, and Malcolm X in their ranks.

At the height of Rosset’s powers, he had sold 100,000 hardcover and one million paperback copies of the “smutty” Tropic of Cancer in the first year. For publishing the banned book, he faced death threats and more than 60 legal cases in 21 states. There were gunshots fired at his home, bombings and break-ins at the Grove Press offices. “It really frustrated him that no one else seemed to understand the urgency or importance of what he was fighting for,” Meyers said.

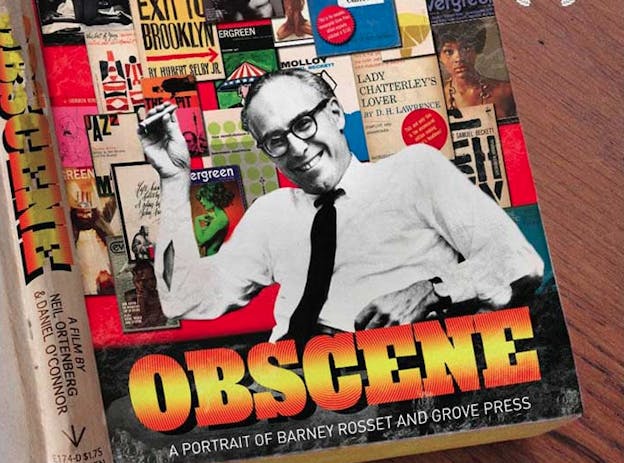

In 2007, five years before Barney’s death, filmmakers Daniel O'Connor and Neil Ortenberg released a documentary entitled Obscene, which cataloged the rise and fall of Barney’s publishing empire. “Neil knew not to show it to Barney before it was released, because Barney would want to change and direct it,” Astrid said. Instead, Barney watched himself star when everyone else did.

The last scene: Barney is slowly, and with difficulty, climbing up the stairs to his fourth-floor walk-up apartment. He looks frail. “There’s this sad music playing,” Astrid said. He’d lost Grove Press to bad business decisions (one of his nicknames was "The Worst, Most Fucked Up Businessman in America"), had married five times—he’d grown old. “He opens the door, he’s alone, and it’s done, that’s the end,” Astrid continued. “He didn’t like that.” The image suggests that Barney’s work was finished, himself a sad, broken man. But that wasn’t the whole story.

Three years after the documentary was released, Barney sold a large part of his archive to Columbia University. “[Columbia] came one day and took everything on this wall—books, binders, films," Astrid explained. “The next morning, Barney woke up, moved the empty bookcases away from the bottom, and he just started painting, he never said why,” she continued. “He had to fill that space. He had to fill that emptiness. He had to feel like change was still occurring, too.”

Astrid, however, never once asked what it all meant. “I wasn’t—given the experience I’ve had with him changing things all the time—surprised. And, he had painted somewhat before,” she said. In fact, he preferred to associate himself with painters, rather than writers. In 1949, his first wife, the painter Joan Mitchell, introduced him to her friends: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline. After Rosset and Mitchell divorced, he remained close to each of the artists.

When Sandy Gotham Meehan, a documentarian, and longtime friend of the Rossets came to visit Astrid just after Barney’s death, she saw the wall for the first time. “I was stunned to see the mural, blazing like a neon sign, along a long wall that had always been covered in books,” she said. Gotham Meehan met Barney years before, while working on a documentary about the publisher. That film never materialized, but the two remained close. “I had seen Obscene, and I was suddenly outraged about the ending of that film—showing him feeble and hobbling up the dark stairs looking sad and alone—when he was really going inside to work on this!” This wall, this mural, Astrid explained to Meehan, would soon be turned to rubble—the building had been sold. “I decided then and there to produce a short film, a visual poem. If it were to be destroyed, at least it would exist on film,” Meehan said.

A short it would have stayed, too, if Astrid hadn’t discovered a note Rosset had written to his friend George Plimpton—the original editor of The Paris Review—on the day he learned about Plimpton’s death. Plimpton, the uptown patrician, had been interviewing Rosset, the downtown pugnacious outré rebel, for a year for a New Yorker profile. Until then, George and Barney had never had much use for each other, but they had bonded in that year of interviews over ping pong matches at the 4th Avenue loft.

“I insisted Lorin [Stein, the current editor-in-chief of The Paris Review] come see the note, as well as the wall,” Meehan said. “When he walked in and saw the wall, his reaction was extraordinary. He stared at it for a while, calling it a ‘thing of beauty… and wonder.’ And I thought, this is a much bigger film.”

There is a wide speculation among those who were close to Rosset that the mural is, in effect, a visual autobiography. Some have called it “Barney’s universe,” or “an epic novel on a wall,” while others believe it was one last joke. Everyone, however, seems to agree that it’s an art critic’s worst nightmare. For an esteemed literary publisher to leave behind a final work so unpredictable—and so large—has understandably baffled those who survived him. David Rose, editor-in-chief of Lapham’s Quarterly, typifies most people’s reactions to the wall. “It’s the most unexpected thing I would have associated with Barney Rosset,” he said. “Of course he would do this, because it makes no fucking sense whatsoever.”

Lorin Stein, in his way, agreed. “Barney was one of the great libertine publishers, who also happened to have great taste,” he said. “I wouldn't have guessed that he'd spend the last years of his life working on a mural involving egg cartons and action figures—but I wouldn't guess that about anyone, really.”

Barney’s close friends carried their detritus four flights up to add to the wall. They brought SONY Walkman packaging, a Korean knife opener, anything made of Styrofoam. Astrid herself bought whatever Barney requested. She’d find him standing in front of the wall for hours, she said, “rearranging and re-painting.”

While interpreting Rosset’s last work may take a lifetime, preserving the wall feels like a more feasible task. Meehan’s documentary, Astrid hopes, will bring awareness to the last work Barney published. Who he was, what he did for American art and politics, and what he left behind: A final piece of art that will continue to divide and provoke, the way his books and his quarterly did for more than 30 years.

“In my early teens, I discovered that any book with Grove Press on its spine was a direct portal to everything my parents were trying to keep me from knowing. Between Grove books and the Evergreen Review, my generation was able to see the world in a different way, sometimes a disturbing way,” Meehan said. “Barney saved my intellectual life. So this film, entitled Barney’s Wall, for me is very personal,” she said. To her, Barney’s mural is a sort of Rorschach test for the intensely creative imagination. “The film is ultimately about Degas' line, ‘Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.’”

Barney didn’t seem concerned with the preservation of this mural, a précis of his legacy: He painted it directly on drywall, four floors up, in a turn-of-the-century East Village apartment, making it difficult (and expensive) to extract without damage. Even so, Meehan’s determination is unwavering. “We’re going to save that wall,” she said. But who will give it a new address?

At the moment, potential homes include The Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, the Astor Place subway station near Rosset’s apartment, and The Museum of Sex. San Quentin State Penitentiary, where a production of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot was once performed, has even been suggested. “Any of those would do,” Meehan said. “As long as it’s not destroyed.”

While saving the mural is the ultimate mission, allowing it to remind us of what Rosset left behind is far more important. “Long after the wall is dust, the cultural contributions—introducing us to Beckett, Genet, Burroughs, so many others—he made will live on,” John Oakes said. “Those actions are more influential, more lasting, than any wall.”

In that wall, there is Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Octavio Paz, Malcolm X, Jack Kerouac, Marguerite Duras, Hubert Selby, Jr., William S. Burroughs. It is fitting that the publisher who brought these people to the forefront of American culture spent his final years bringing them together again for one last performance.

The documentary, Barney’s Wall—co-produced by Sandy Gotham Meehan and Williams Cole—is currently in post-production, and will be submitted to film festivals around the world. The mural is housed at 61 4th Avenue, which is scheduled to be destroyed in June of this year.

An earlier version of this article stated that John Oakes said "The least of his contributions was reshaping American culture", when in fact he said "That is the least of his contributions: he reshaped American culture". It has been updated to reflect the correction.