Back in 2011, about a dozen Swarthmore students with little experience in advocacy launched the first college campaign to divest from fossil fuels after having learned about the strategy in their peace and conflict studies class. Weeks ago, the Swarthmore campaign suffered its largest setback to date. The school’s Board of Managers, worried about the return on investment for its $1.9 billion endowment, refused to divest from coal, oil, and gas companies.

Despite the losses, campaigns to divest from fossil fuels have only gained momentum. Today, about 230 organizations, including roughly 30 schools, have committed to divestment. In September, the environmental group 350.org estimated divested assets totaled $50 billion, and less than a year later, it expects the number to have doubled.

For all the movement’s achievements, academics, especially economists, remain split on whether divestment is a good use of resources. Critics don’t deny the costs of climate change but question activists’ priorities. “If you want to do something about climate change, then you have to do something about prices,” said Frank Wolak, an economist at Stanford University in California. “You are not going to solve the problem by beating up on companies.”

After all, there’s enough for climate activists to worry about already—like Congress’s refusal to pass a carbon tax and the too little, too late nature of the international climate deal coming together in 2015. In that sense, divestment is as symbolic as the campaign against the Keystone XL pipeline, which would carry tar sands oil through North America and contribute significantly to climate change, protesters say. Many of the same faces—including 350.org co-founder Bill McKibben—are behind both campaigns.

“We need to focus on actions that are going to make a real difference,” said Robert Stavins, an environmental economist at Harvard and a vocal critic who argues that advocates would do better focusing on an economy-wide carbon tax.

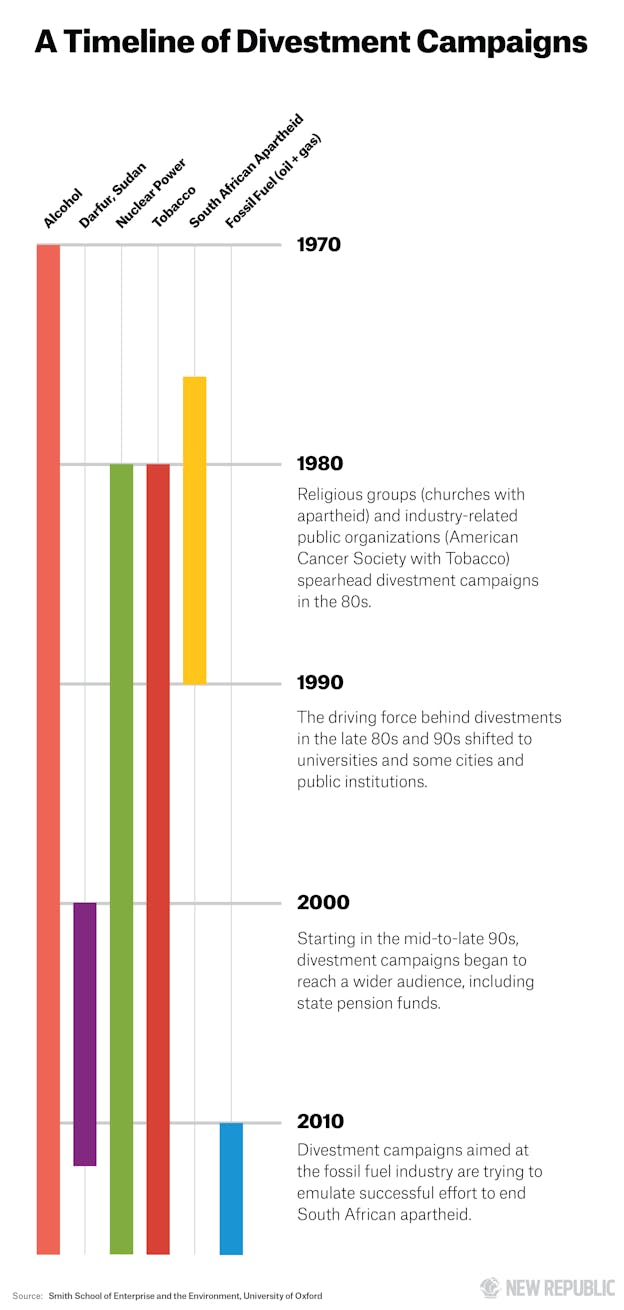

If divestment campaigners' only aim were to move markets, they’d have a point. It’s near-impossible to prove that divestment alone has ever had any financial bearing on their targets. Even the impact of divestment campaigns widely considered a success—like South Africa's apartheid in the 1980s and tobacco in the 1990s—is unclear.

Does that even matter?

Divestment is not a strategy in itself, but a useful tactic for driving home the message of the broader campaign: In the case of climate change, the message is how the world needs to transition away from fossil fuels, and relatively fast, if it hopes to combat global warming. In the 1970s and ’80s, divestment was the magnifying glass to focus attention on the United States government’s apathy toward apartheid and Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment in South Africa.

It took decades for the campaign to be taken seriously. By the ’80s, students were staging sit-ins on campuses and building shantytowns. Major schools—including the University of California, Yale University, and Harvard University—religious institutions, and corporations promised to fully or partially disinvest from South Africa. Getting the corporate world to sign on was a particular challenge, but General Motors and IBM withdrew from South Africa as well. “There was a real tension within the business ethics of what you do when you’re investing in a country whose laws are unethical,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison sociology professor Gay Seidman, an apartheid activist at Harvard at the time. “Most of the people working in the divestment movement through the 1970s and 1980s weren’t doing it to simply to get the institution to divest,” Seidman said. “It wasn’t about the institution; it was about a broader issue. We wanted people to think about apartheid.”

The tobacco divestment movement borrowed heavily from the apartheid movement, but the campaigns originated in distinct ways. Public health experts and doctors led the calls to divest pensions and university funds from Big Tobacco.

Both are considered a success—though not because they financially impacted their targets. They didn’t. Financial hardship was never the goal; the goal was political action.

A 1999 study, for instance, did not find that divestiture impacted South Africa's economy. The campaign's effect on Congress may be more difficult to measure, but public pressure did eventually result in political scrutiny and legislation. In 1986, Congress passed sanctions on South Africa. Though there were many moving pieces, within years apartheid ended and Nelson Mandela was released.

On tobacco, divestment helped to highlight the decades-old tactics the industry used to mislead consumers on the health impacts of smoking. The scrutiny paved way for new taxes, limits on smoking in public spaces, and other policies documented to change public behavior. The symbolic resonance of schools like Harvard, University of Michigan, and Stanford divesting was much more important than the amount of money pulled. Over the course of the campaign, only 80 funds ever divested (out of thousands of funds total), but this too was considered a success. By financial measures, the campaign was a failure—since the ’90s, tobacco companies’ stocks have only grown, a sign that divestment didn’t hurt the industry’s long-term success.

“This was never something that I thought was very important to tobacco control policy,” says University of Michigan Dean of Public Health Kenneth Warner, a tobacco health expert who sat on the school's committee to determine if it would divest. Policies, not divestment, have had the greatest impact on tobacco, such as raising taxes on cigarettes and banning smoking in public places.“It makes a statement and that’s the most important thing it does,” Warner said.

The fossil fuel campaign has borrowed heavily from the past, with its sit-ins and rhetoric about holding institutions to moral standards. Yet there are some key differences, namely the speed with which divestment has caught on in the U.S. and abroad. It has taken a matter of years, while for apartheid and tobacco it took a decade to get to this point. Social media has certainly played a role in the pace.

The victories at some schools, like Stanford University, surprised organizers themselves. Faculty were circulating a letter to send to administrators when Stanford announced it would divest from coal companies last year. “The fight is just as important as the win in a lot of ways,” McKibben told me. “Sometimes you can win almost too quickly in some of these battles. Instead, when you have to spend a few years fighting, then every freshman and faculty member and parishioner will come to know the story of why it’s so important.”

At MIT, which hasn’t relented, scientists have taken the lead in arguing that the school’s commitment to scientific integrity means it should commit to divest from companies advancing climate change denial. “You sit in the lab trying to make the world a better place,” PhD student and divestment activist Geoffery Supran said. “This is the institution [where] you came to do that. It’s very personal for us." Supran said MIT's activists are “specifically focused on the issue of: Is it okay for MIT and other universities to fund fossil fuel companies that we can prove" have funded disinformation about the climate. "That certainly is a narrative that has most caught the ear of the administration,” he said.

The climate movement in some ways has the most difficult goal: To convince people to divest from energy we rely on every day, from stocks that make up a massive part of the economy. They perform well, too. In absence of climate legislation, these stocks will continue to perform well, especially oil and gas. An average 10-year return on investment for oil and natural gas stocks at 11.5 percent, higher than the overall 5.6 percent returns on college endowments, according to the oil trade group American Petroleum Institute.

Any divestment campaign has its limits. The financial market globally is $212 trillion, while global university endowments only account for close to $450 billion. Of that endowment pot, fossil fuels probably make up somewhere between 2 to 5 percent (most endowments aren’t public). That’s still a big portion of the economy. Global university endowments, at $450 billion, are a small drop in the bucket of the global financial market. Their portfolios are typically invested somewhere between 3 to 5 percent in fossil fuel accounts—tiny in comparison to the industry’s $4.5 trillion total. Plenty of investors are willing to jump in when a university divests its stock.

Activists see these as straw-man arguments. What they’re doing doesn’t distract from the (slow-moving) national and international policy debates. If nothing else, they’ve attracted new allies to push for exactly these policies. “Nobody can deny it’s already changing people’s lives. It’s changing the lives of myself and tens of thousands of students,” Supran of MIT said, who’s decided to continue his climate change activism after graduation.

Endowment managers have their own concerns when they look at the campaign to divest. They worry that demands will spiral out of control, expecting divestment from other industries and countries. Since it can easily engage student bodies on college campuses, divestment has been a popular tactic for dozens of other campaigns, though they've achieved varying degrees of success. The most recent campaign to pop up on campuses has called for disinvestment from Israel. In the past, the targets were Darfur investments, as well as the guns, gaming, fast food, alcohol, and porn industries.

Yet, climate change is a slightly different kind of movement. The reasons divestment is an attractive option are exactly why climate change is so difficult to solve: It affects everyone, but over a long time period, and corporations today hold a disproportionate power over young people's future.

Not every divestment campaign reaches the critical mass necessary, attracting larger and larger institutions to the cause. A study on stranded assets (the idea that fossil fuel assets will lose value due to climate change policy and become “stranded”) from the University of Oxford noted that divestment's ability to stigmatize “poses the most far-reaching threat to fossil fuel companies.”

All signs point to the climate movement already hitting this stage.

“I think a tipping point may have been reached within the last six months,” University of Oxford economist Ben Caldecott, who has studied the impacts of divestment, told me. “It hasn't been one single event, but rather a series of announcements, coverage from respected investor commentators, and developments among central banks, as well as countless conversations with mainstream investors now suggesting they are now taking seriously the fact that environment-related risks are material financially and can strand assets.”

For McKibben, who’s credited for elevating divestment in a 2012 Rolling Stone article and accompanying “Do the Math” tour, that turning point came when the Rockefeller Foundation—the family the built its wealth with the oil industry but has since invested in finance—announced on the eve of the massive People’s Climate March in New York City last September that it would divest its $4 billion holdings from fossil fuel stocks. “That was huge,” McKibben said, for both symbolic and financial reasons.

Whatever the turning point was, it’s clear climate activists have already outpaced past campaigns.

Financial investors are beginning to look at the risk associated with fossil fuels, and some are backing away from coal, the dirtiest energy source. In May, Bank of America announced it will begin to pull coal investments, citing it as a risky investment. HSBC has likewise estimated that regulations on coal after 2020 could cut assets by up to 44 percent. The possibility that divestment could affect demand for coal has crept into Peabody Energy's SEC filings—a bare minimum level of acknowledgement that they’re concerned, but still a start.

McKibben pointed to Peabody Coal citing divestment briefly as a financial risk in an annual SEC report as evidence that the campaign is working. It’s clear “we’ve changed the way the financial industry is now thinking about fossil fuels.”

However, that sentiment needs qualification: Most investors aren’t driven by public campaigns, but they do look at the risk of the investment and the likelihood of future regulations. Conceivably in the near future, if policies curbing carbon regulation truly take hold, investments in fossil fuels might become what’s known as stranded assets. What’s advocacy’s role in all this? “The campaign is helping to accelerate that process,” Caldecott said.