The 2014 midterm was the election of fear, and offered a likely foreshadowing of the strategy the Republicans will use to try and win the White House in 2016. In the midterms, the GOP stacked up impressive victories by brilliantly stoking a nightmare vision of an America about to be overrun by Ebola patients, anchor babies, and ISIS assassins. In their quest to replace Barack Obama, Republican presidential hopefuls are making the starkest possible case that security is the primary issue, eclipsing all others.

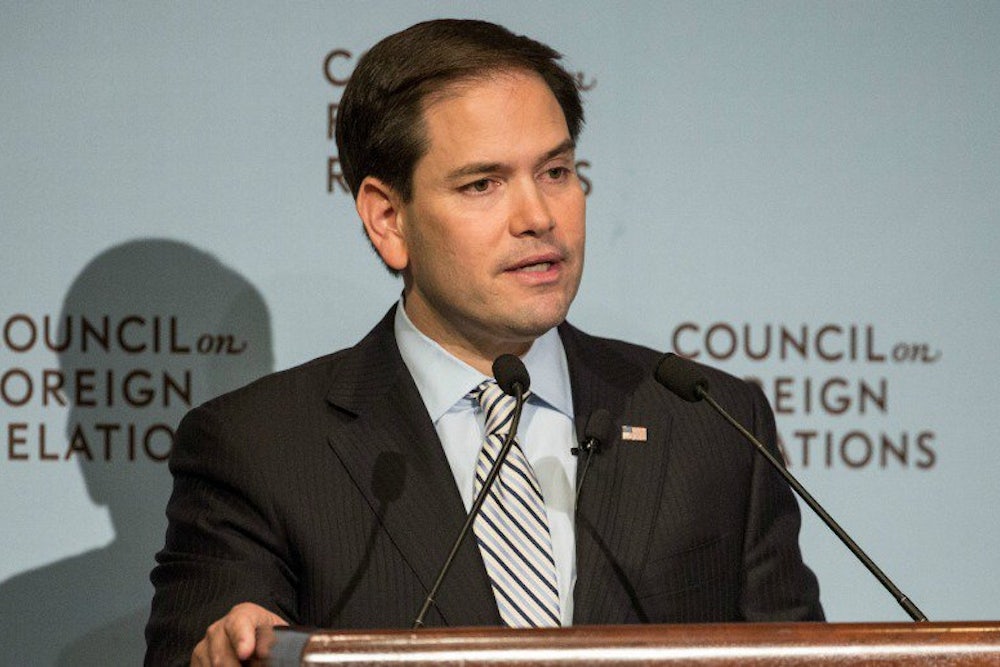

Yesterday, Marco Rubio announced the new theme of his campaign: “The fundamental problem we have in America is that nothing matters if we aren’t safe.” According to Rubio, “The world has never been more dangerous than it is today,” which means “the economic stuff” has to take a backseat to national security. Rubio’s emphasis on safety echoed a remark made by his rival Chris Christie the same day: “You can't enjoy your civil liberties if you're in a coffin.”

These statements are startling in the all-or-nothing choices they offer. Without security, “nothing matters.” If we don’t have security, we’ll be in a coffin. This black-and-white language negates the possibility that security is one value among others, that it needs to be balanced against competing values such as liberty or peace. It’s hard to imagine cruder appeals to fear.

And by appealing to fear in the name of security, they only ensure they’ll get less of what they say they want.

While some political leaders have relied on fear-mongering since time immemorial, the specific national security based anxiety voiced by Rubio and Christie has a particular lineage. According to George Mason historian Peter N. Stearns in his 2006 book American Fear, “American culture launched a really distinctive approach to fear only in the twentieth century: There was no long legacy of public fearfulness. Indeed, current standards are particularly striking in their contrast with nineteenth-century norms, which quite explicitly called on Americans, at least American men, to face fear directly and stare it down.”

Stearns locates the origins of fear culture in modern American politics in the Cold War. His argument is in keeping with findings of many historians that the very idea of “national security” as a pre-eminent goal crystallized in the early days of America’s rivalry with the Soviet Union, when Secretary of State Dean Acheson said it was necessary to “scare the hell out of the country” in order to shore up support for an anti-communist foreign policy.

In his 1974 work The Logic of World Power, historian Franz Schurmann argued the Cold War consensus was based on “a new ideology” and “the key word and concept in that new ideology was security.” For Schurmann, part of the power of the concept of security was that it encompassed domestic economics as well as foreign policy. Social Security, after all, was the cornerstone of the New Deal. The promise of “national security” as a foreign policy goal was that it would bring the same type of peace of mind that Social Security gave to citizens.

In practice, the excessive weight given to security produced not greater calm but more fear. The search for absolute security could brook no opposition, so the enemy became not just Stalin’s USSR but the idea of communism, leading to a global crusade abroad and an ideological purge at home. As the conservative foreign policy analyst Robert W. Tucker noted in his 1971 book The Radical Left and American Foreign Policy, “By interpreting security as a function not only of a balance between states but of the internal order maintained by states, the Truman Doctrine equated America’s security with interests that evidently went well beyond conventional security requirements.”

The hair-trigger overreactions of the early Cold War were revived after 9/11, when policymakers once again launched a global war on the grounds that it was needed to ensure security on the home front. The best articulation of the post-9/11 culture of fear—and the concomitant willingness to do almost anything to secure an impregnable level of safety or security—can be seen in the 1 percent doctrine as articulate by Vice President Dick Cheney: “If there's a 1 percent chance that Pakistani scientists are helping Al Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response.” In effect, Cheney was calling for the United States to become one giant safe space, even if it meant massively overreacting to threats abroad.

Because of the language of security originated in the New Deal, the earliest critics of this discourse came from the political right. Throughout the early Cold War, Ohio Senator Robert Taft, the stalwart of the Republican right, warned that America was becoming “a garrison state.” In his libertarian classic The Road to Serfdom (1944), F.A. Hayek argued that, “nothing is more fatal than the present fashion among intellectual leaders of extolling security at the expense of freedom. It is essential that we should relearn frankly to face the fact that freedom can be had only at a price and that as individuals we must be prepared to make severe material sacrifices to preserve our liberty.”

Hayek was of course writing about the economic realm, but his insistence that security needed to be balanced against liberty applies just as well to foreign policy. If Rubio and Christie had any interest in moving beyond the politics of fear, they could do well to read that earlier right-wing thinkers warned that the idolatry of security brings not safety but unending jitters and a loss of liberty.