I was eleven years old in 1994 when I started watching Late Show with David Letterman. My mother’s depression had gotten worse and her drinking more frequent. When I was younger, I tended toward Super Mario Brothers and The Baby-Sitters Club as distractions. Letterman was a different kind of outlet. His dry humor seemed to cover up a deeper unsettledness, both his and mine: He reveled, or wallowed, in the mediocrity of reality. On weeknights, I recorded the show for the next afternoon, and used it to tune my mother out on her bad days.

Eventually, the demons that ruled my mother won. On September 15, 1995, the day she was scheduled to appear in court for assaulting a police officer, she took her own life. It had not occurred to me that she would kill herself. Her anger while drinking was so outwardly focused, I had thought she might hurt one of us. It’s possible that she thought suicide was a way to ensure that she wouldn’t be a threat to us anymore. She may have felt she had run out of options, or chances.

Family and friends descended on our house in the weeks following, saying with stunned sincerity that we should call if there was anything they could do. Then, my father and I were alone together. Though we had spent plenty of time that way over the years—my mother was a waitress and worked dinner shifts—there seemed to be less to say now.

Enter David Letterman, reliably recorded on the VCR, ready to go while we ate dinner on TV tables. My father and I jumped back into our routines a week after my mother’s death: school, extracurriculars, and homework for me; long days at the auto repair shop for him. I cooked the starch and vegetable each night and he took care of the meat. We would have the usual exchange about our days. Letterman picked up where we left off. In an odd way, his embrace of dark absurdity was perfect for us: After all, what could be more of a non sequitur than the suicide of a 33-year-old wife and mother.

In May 1996, Letterman appeared on Larry King Live, and I called the show during the question-and-answer portion. After a slew of busy signals, I got through.

“Hi, um, Dave?” I asked. “I’m 13, and I’ve been watching your shows for two years and I’ve written letters to you. And I was just wondering…”

“You would like me to adopt you?” Dave interrupted.

“Yeah, that would be pretty cool!”

“All right, just send along the forms, we’ll have them notarized,” Dave replied.

“What’s your question?” Larry King interjected.

“I’m wondering if you can lower the age limit to come see the show,” I said. “I’ve written letters and they’ve sent me postcards saying you have to be sixteen.”

“Well, let me tell you something,” Dave said, leaning in. “The kind of show we do gets better and better every day. So, you’re actually in a good position because as good as the show is now, in three years, you won’t be able to stand it.”

As always, I was recording. It only took a few days for my tape to begin to wear out. I played it at school repeatedly. Everyone wanted to see David Letterman adopt me on television—or, I wanted everyone to see David Letterman adopt me on television. People started calling me “Jamie-Lee Letterman.”

Since I had gone from smarty student council rep to Girl Whose Mother Died earlier in the school year, I was determined to perpetuate my new identity as Dave’s daughter. Six months after my moment on Larry King Live, my neighbor Gail got tickets to see The Late Show. Before I had discovered that I needed to be 16, Gail had requested tickets. Like many of the adults in my life, she made sure I was keeping busy. But did the age requirement mean she had to find someone else?

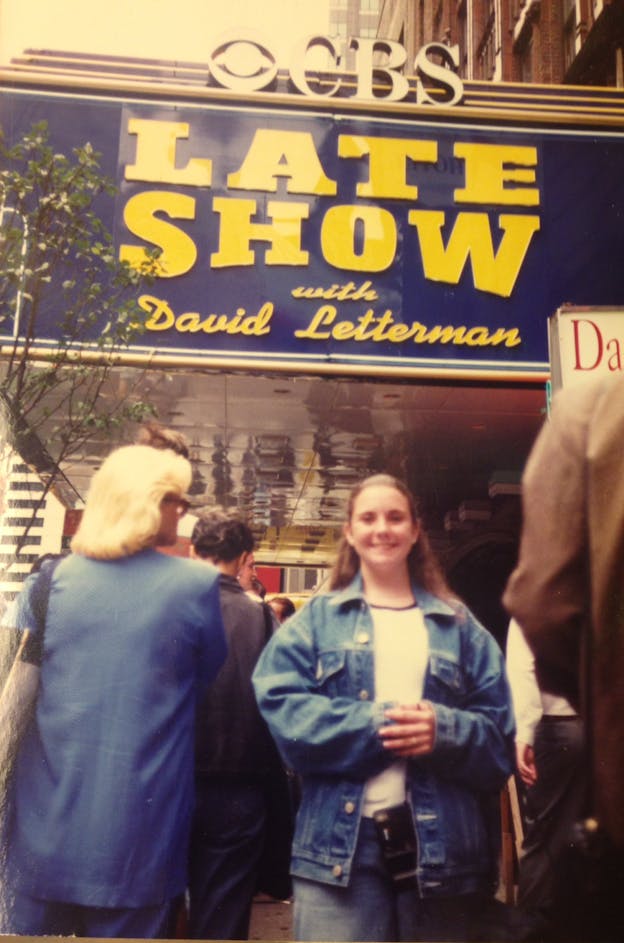

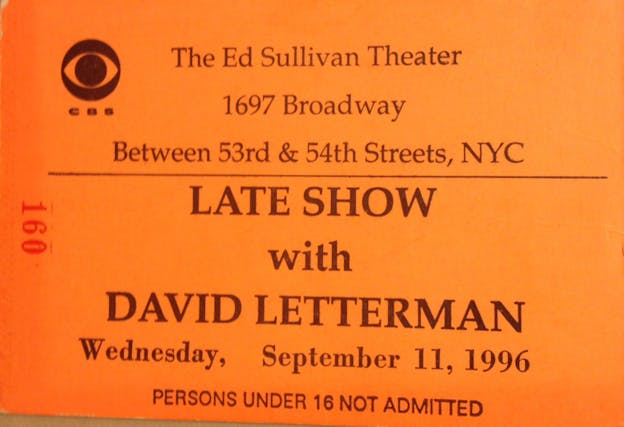

Absolutely not, I said. I asked my father for my birth certificate. Within a day, thanks to a matching font on Microsoft Office, a glue stick, and my school’s photocopier, I had a document that stated I was born in 1979, not 1982. The next week, I was in front of the Ed Sullivan Theatre on Broadway. Not surprisingly, no one asked about my age so the fake birth certificate remained in my pocket. Gail and I were seated in the fourth row. Beck’s “Where It’s At” blared.

Before long, Dave appeared for his warm up of questions and answers. My hand shot up. “Yes?” he said.

“Hi, Dave. I don’t know if you remember, but I talked to you on Larry King Live last spring. You said you were going to adopt me.”

He didn’t miss a beat. “Weren’t you the one that was too young to come to the show?”

“Uh, no.” I shook my head as I looked around faux-uncomfortably. I was now doing a bit of my own. I pointed at Dave. “But, you did tell me that you’d take care of the adoption paperwork.”

Dave laughed. “Sure, I’ve got the forms upstairs. What’s your name?”

“It’s Jamie-Lee.”

“Well, now it’s Jamie-Lee Letterman,” Dave replied. “If you’re going to be my daughter, you’ve got to do something for me, okay? You’ve got to MAKE DADDY PROUD!” Over the laughter, he yelled again. “MAKE DADDY PROUD!” With that, it was time to begin taping. Dave trotted backstage. The band struck up the theme song.

In the midst of the jokes about the Clinton-Dole presidential race, Letterman paused. “Ladies and Gentlemen, I’m a little nervous tonight because my new daughter is in the audience. Jamie-Lee, where are you, honey?” The cameras turned to me. I clapped and waved with both hands and bounced around, unable to control my excitement.

“Beautiful.” He blew me a kiss. “Now, study hard, get to bed early. MAKE DADDY PROUD!”

The audience roared.

By the time this VHS recording made the rounds at school, my new identity was complete. I wore my Late Show t-shirt so often that a friend once told me that she thought of the gray shirt with yellow and blue lettering as my uniform.

I continued to watch The Late Show regularly, but at some point, the VHS recording stopped and I settled for the occasional viewing. I tuned in for episodes I sensed would be notable: his first following 9/11, Darlene Love’s Christmastime appearances, “Guess Mom’s Pies” on Thanksgiving, or any time Regis, Robin Williams, or Richard Simmons showed up. I even went back to the Ed Sullivan theatre a few times over the years, though nothing happened on my subsequent visits. It wasn’t disappointing; instead, it felt like I was paying respects to my 13-year-old self who hit the Letterman jackpot when I so needed it. I’m not willing to say that my fandom faded as I grew older, but as the years passed, my grief over my mother’s death settled into its long-term form and I needed Dave less. Or, I knew he was there when I needed him, and that was enough.