The silence must have frightened Emily Wilsey. In the seven months since her husband had gone to war, Captain David Wilsey, a 30-year-old anesthesiologist with the 116th Evacuation Hospital, had never gone more than a day or two without sending her a letter. Every step of the frigid, mud-soaked, and bloody Allied advance across France and Germany, he had written to her of his experiences. But now, with victory assured and the newspapers declaring the war in Europe all but over, the letters had stopped.

His last letter, dated May 1, 1945, was sent from “Somewhere Else Yet Again, Germany.” He had written about how excited he was that his unit would get the chance that night to see The Keys of the Kingdom, a movie starring Gregory Peck. He marveled over how fast the latest issue of the Elko Daily Courier, the daily paper in their town in Nevada, had reached him. “The advance party is out to reconnoiter the new site we will move to in a day or two,” he added, making his first reference to the Dachau concentration camp. Dachau opened in 1933 and was initially used to house political prisoners. It later became a training facility for the SS, the elite Nazi military force responsible for planning and executing the “Final Solution,” or the annihilation of the Jews. An estimated 41,500 prisoners were murdered there. Some went to the gas chambers, or were shot or beaten to death; others expired from exposure or starvation, or died subsequent to medical experiments conducted by SS doctors. Dachau was the inaugural Nazi concentration camp and served as a model for their massive killing system. “The war could end any hour yet we keep moving, racing, working just as if it weren’t over,” he told her, closing the letter by writing, “I love you,” to his wife nine times in four long rows.

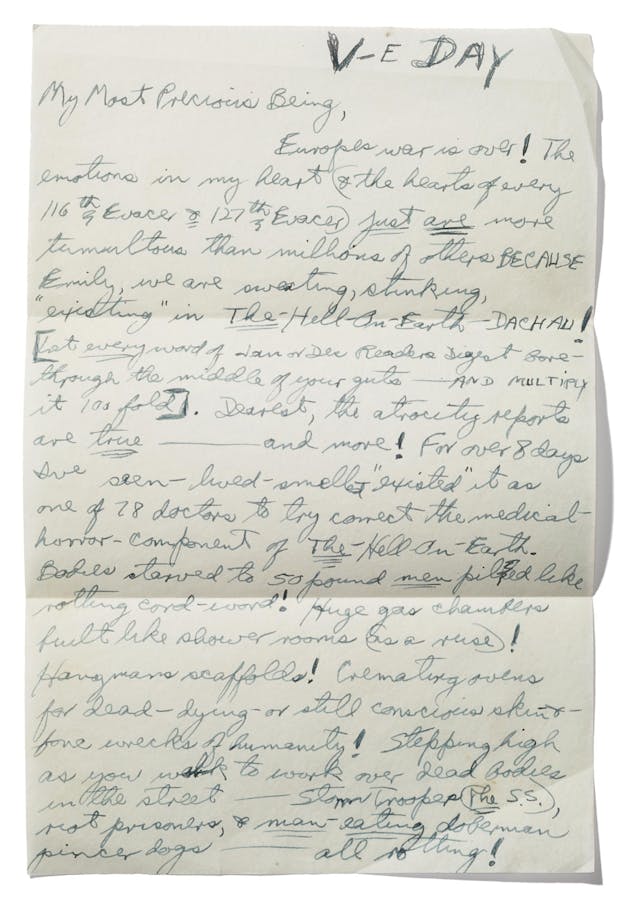

Then a week of uncharacteristic quiet. When the letters finally resumed, her loving, joking, open, and optimistic husband had been transformed by what was evidently the defining trauma of his life. On V-E Day, May 8, 1945, David Wilsey began a seven-page letter to his wife, addressing her as “My Most Precious Being”:

We roared through the gates of Dachau figurative “minutes” after its liberation while 40,000+ wrecks-of-humanity milled, tore, looted, screamed, cried as/like depraved beasts which the Nazi SS has made them. In those early “minutes,” I saw captured SS tortured against a wall [by U.S. soldiers] and then shot in what you Americans would call “cold blood”—but Emily! God forgive me if I say I saw it done without a single disturbed emotion BECAUSE THEY SO HAD-IT-COMING after what I had just seen and what every minute more I have been seeing of the SS beasts’ actions. . . . AND! To think this is only “The Queen Bee” camp—others are worse though much smaller and it is here the “policies” were worked out for the lesser camps. In fact, this Dachau is THE home of SS Bestiality—Himmler’s “laboratory” and hangout.

. . . It is not only structurally the equivalent of a city of 50,000 but it is the warehouse/supply point for hundreds of thousands more SS troopers. Thus I (yes, I!) and others have “liberated” (call it looted if you will) warehouses for three intensive days and five less intensive days. Dear, I just can’t even start to touch upon all that is stored here after years of Nazi looting the Continent of Europe.

If I turned you loose in the Chicago downtown Loop of five square miles, you would find every item there and here. Maybe I’m raised “different” but I’m still not a “good” looter. However, I have hundreds of smallish items that are of practical value. We regret only that we each don’t have one freight car apiece to go to the USA in—it’s PHENOMENAL/STUPENDOUS! I’ll only mention a few: a fine deer rifle, twin sweaters for you and I; silk smock for your house—”hasty” work; beautiful and expensive punching bag; I passed over most of the beautiful Dresden-ware; anesthesiology equipment; fine optical lens equipment (I missed the best); swords-tools-machinists apparatus; fountain pens; lotions; Swastika & SS banners to decorate our Rumpus Room, etc etc.

In that first letter and the many that followed, Emily Wilsey was an audience of one for an account of the end of the war in Europe that has never been a part of the accepted iconography of the Allied victors. In the respectful, carefully presented narratives found in Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation, the works of Steven Spielberg, plus countless other books, articles, museums, galleries, and radio shows, and much more, the American G.I. has been canonized as an altruistic and honorable moral opposite of our unspeakably cruel and vicious enemy.

Wilsey’s letters complicate that sanitized picture of the G.I., revealing him instead to be what he was in real life: undeniably heroic, courageous, dutiful, dedicated, brutal, vengeful, and ethically compromised. On May 22, Wilsey wrote to his wife:

Did I “confess” how PASSIVELY my canteen cup was used to pour icy riverwater down SSers half-naked backs as they stood for hours with a two-arm-up-Heil Hitler before being shot in cold blood? A truly bloodthirsty (I’d never seen it before) combat engineer from California asked to borrow my cup in performing his “preliminaries” to roaring his .45 automatic right into the face of 3 SSers. He was bloodthirsty and nothing else would have ever “satisfied” that boy for his brother’s death at the hands of the SS.

Reports of American soldiers killing as many as 50 fleeing or surrendering SS troops and other German POWs emerged not long after the liberation of the camp. In June 1945, the U.S. military issued a report titled “Investigation of Alleged Mistreatment of German Guards at Dachau,” which recommended courts-martial for several soldiers involved in the abuses. General George S. Patton dismissed the charges, and they were never adjudicated.

The violence has been described before in Holocaust and World War II literature, but typically as “heat-of-the-moment” violence, unthinking blows struck, in the words of one U.S. military judge-advocate, “in the light of the conditions which greeted the eyes of the first combat troops.” What sets Wilsey’s account apart, then, is that his unit didn’t arrive until three to four days after the camp was liberated. The combat engineer using his canteen was not a soldier on a battlefield but a grieving, shell-shocked veteran conducting an extralegal revenge execution.

Other letters Wilsey sent to his wife suggested the killings continued, even after V-E Day. “These incidents find no place that I know of in the popular American narrative of World War II and the Holocaust,” William Donahue, a professor of German studies at the Center for Jewish Studies at Duke University, told me. “To most people, this is a very different side of a piece of history we all thought we knew,” said Robert Abzug, author of a 1985 book on the Dachau liberation titled Inside the Vicious Heart: Americans and the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camps, which relied heavily on letters from U.S. soldiers.

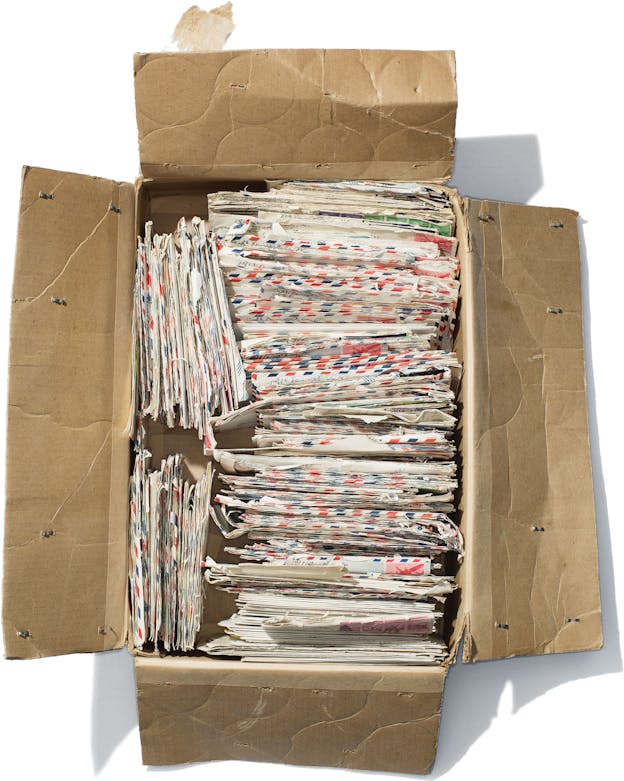

The Wilsey cache of letters is invaluable, and perhaps even unprecedented, because of its volume—hundreds of letters, sent over a span of nearly five years—and the bluntness of its depictions of the war. Along with the executions of SS soldiers, the letters described instances of heroism (“trying to save a good-looking German eight-year-old who had stepped on a mine with resultant nine holes in his intestines, half a foot off, and hundreds of minor fragments in his upper legs, arms and face”); withering criticism of Wilsey’s commanding officers (“such incompetent, unqualified, mentally inferior people”); racial bigotry (“the colored boys have been accepted ‘whole-heartedly’ (if not ravenously) by women-across-the-Atlantic”); and widespread looting of Nazi possessions, much of it, in all likelihood, previously looted by the Germans from their Untermensch victims across the continent.

Emily Wilsey’s replies to his letters did not survive the war. Troops on the front were ordered to destroy most mail. Their three children, in their sixties and seventies now, knew nothing of the letters until after her death in 2008, when they were cleaning the family home to prepare it for sale and discovered them in a trunk in the attic.

David Wilsey, who died in 1996, never spoke in detail of the war. “We never got to ask either of them questions,” said Clarice Wilsey, who now has the letters at her home in Eugene, Oregon. “That’s how they wanted it, I guess.”

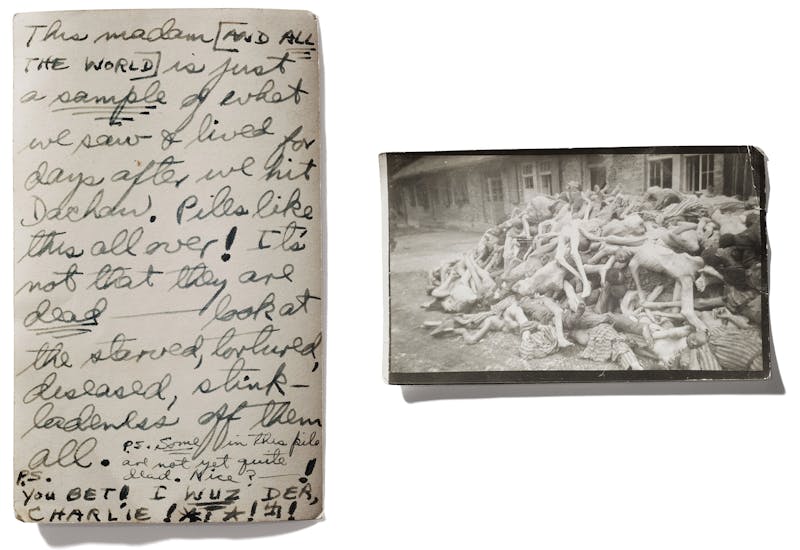

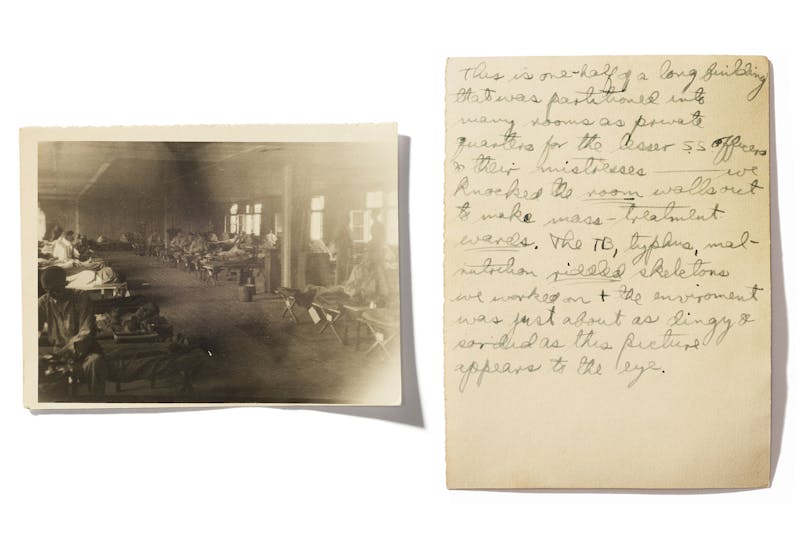

Clarice Wilsey trembled in the face of the anger she had incited in her father. It was 1953, she was six years old, and David Wilsey had recently relocated the family—Emily, Clarice, three-year-old Sharon, and nine-year-old Terry—to a new home in Spokane, Washington, where he had started an anesthesiology practice. Clarice was poking through a packing box left on the Formica kitchen table in the chaos of the family’s move. There she discovered a gruesome photo collection: black-and-white shots of emaciated, naked corpses, and a long room lined with beds of near-nude people being pored over by white-coated medics. He ripped them away from her. “Where did you find these?” he yelled when she showed him the photos. “You are not to see this. This is not for little girls!”

That moment, Clarice told me, was emblematic of her father’s many contradictions. He could be furious and protective, angry and loving, publicly outgoing but privately brooding. “When I was younger, he was very critical, very in my face, very controlling,” she said. “Yet now that I look back, I see in some ways he was doing that to protect me. He used to accuse us of being spoiled. Maybe to him, when he compared us to a child at Dachau, we were.”

Clarice’s younger sister, Sharon, described her father as an involved but intimidating man. She said that he taught the children to swim himself, but then would grade them on their progress, and not generously. (Clarice: “Most of the time I got a B- or a C+.”) He was not a man who expressed much satisfaction with his children. “I felt like at times I didn’t measure up to what he wanted,” Sharon said. “He was sitting on some anger.”

Clarice and her siblings were peripherally aware that their father had served in the Army and was involved in the liberation of Dachau. But Wilsey was never the sort to appear at Memorial Day parades wearing his dress uniform or the Bronze Star that he earned, according to his discharge papers, for overseeing more than 5,000 anesthesia procedures in Europe. (“Due to his efforts, no time was lost in awaiting anesthesia and seven operating tables functioned simultaneously,” the form reads.) The children were forbidden to look into the beaten-up green Army trunk Wilsey kept in the attic. None of them remember being told not to touch it, but, Sharon said, “it was always understood.”

The closest Wilsey ever came to discussing his experiences in Europe were his enraged responses when anyone appeared on the news to suggest the Holocaust had not happened. “You do not deny this. I saw it, I was there,” he’d say to no one in particular. “They can’t deny this.” Wilsey was deeply taken with Spielberg’s concentration camp film, Schindler’s List, and Clarice would occasionally use the movie as an opportunity to gently suggest he open the trunk. “He seemed to be considering it, but then he shut it down,” Clarice said. Even after Wilsey’s death, the trunk remained in the attic, untouched by edict of their aging mother. “This was a man with another side we were either explicitly or implicitly not permitted access to,” Clarice said.

It wasn’t until shortly after Emily died in 2008 that Clarice had a chance to look inside the trunk again. Sharon, Clarice, and Terry had gathered to empty the Spokane home and prepare it for sale, when Terry climbed into the attic to get things organized. And there was the trunk, wedged into a corner against the brick chimney, covered in a thick film of dust, buried between boxes of old sweaters and abandoned furniture that had accumulated over a half century. “To be honest, I really didn’t have a whole lot of curiosity about my father,” Terry told me in late April. “Still don’t, really.”

He was interested enough to call for Sharon to come to the hallway where the attic ladder hung. When she did, she was confronted by a large Nazi flag unfurled from the opening in the ceiling. The flag and another box had been inside the trunk. The swastika on the flag was larger than her head. “I’m going to be sick,” she cried as she raced down to the family room to fetch Clarice. “We just burst into tears,” Clarice said. “We didn’t know what to make of our father even having such a thing.”

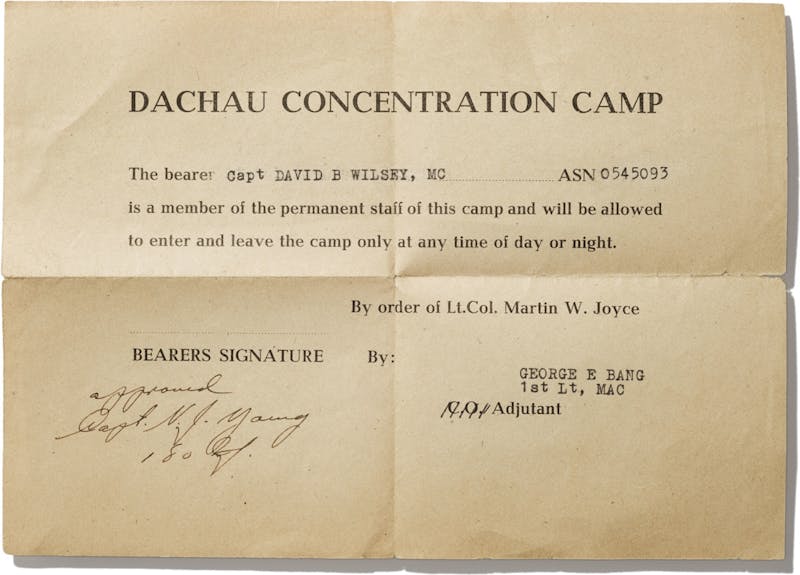

Terry maneuvered the trunk downstairs. They were in a hurry to finish with the house, so they didn’t look inside, and Clarice took the box home with her. She didn’t open it until a few months later, and inside, to her astonishment, she discovered the photos she had stumbled across 55 years earlier. Also there was her father’s Bronze Star, the faded yellow paper that served as his entry and exit pass at Dachau, a Red Cross armband, and an assortment of 1940s-era German and French money. Shards of broken glass, which may have been shattered medical microscope slides, littered the bottom of the box. Amid the detritus was the real find: the letters that David had sent to Emily more than six decades earlier, neatly organized in chronological order.

Even now, so many years later, Clarice said she felt anxious about reading the letters: Her father’s disapproval loomed over her. Still, she pulled out a few envelopes and began with one dated May 8, 1945, V-E Day:

Dearest, the atrocity reports are true—and more! For over 8 days, I’ve seen-lived-smelled-”existed” it as one of 28 doctors to try to correct the medical-horror component of THE-Hell-On-Earth. Bodies starved to 50-pound men piled like rotting cord-wood! Huge gas chambers built like shower rooms (as a ruse)! Hangmans scaffolds! Cremating ovens for dead-dying or still-conscious skin-and-bone wrecks of humanity! Stepping high as you walk to work over dead bodies in the street—Storm troopers (the SS), not prisoners, and man-eating Doberman pinscher dogs—all rotting!

Another letter recounted some of the atrocities of the camp, as told to Wilsey by a Dutch resistance fighter who had been captured in 1943:

A captured escapist was tied by the SS naked to a post, and three of these huge Dobermans (after four days of being starved) were turned loose on him while thousands of internees witnessed it all standing at attention. Hans withstood the calves torn off, withstood the thighs torn off, withstood the guts (yes, guts) turned out. But he turned his head and vomited when the Dobermans had torn the lungs and heart out. The first thing the liberated internees did was to shoot the Dobermans and their horrid handler.

Others revealed a deep, effusive, even sweet man, a man they hardly knew. Wilsey ended all his letters with “All my love, Dave” or, simply “AML.” In mid-July 1945, he wrote to Emily that the 116th was going home, but that he wouldn’t be with them. He’d been assigned to another unit. “You keep your head up, I’ll keep my head down, till we can daily live all our love,” he wrote. “I never saw my father be this loving to any of us, and least of all mother,” Terry told me. “It’s like a whole new version of him,” Clarice said.

The passages describing the atrocities he witnessed affected them the most. “I never cried so hard in my life because of the horror of what I was reading,” Clarice told me. “It just gave me a clarity about why he was so upset about the war.”

Despite those first moments of discovery in 2009, none of the Wilseys made an effort to dig into the box of letters in any depth. Clarice scanned a few to show archivists at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, in Skokie, and both have expressed interest in hosting the collection. But in the six years since they unearthed the cache, the vast majority remain unread by the family. “It’s just so overwhelming,” Clarice explained. “There’s so much.”

The tenor of Wilsey’s letters changed when he reached Dachau. He’d always been a somewhat critical person, but he balanced his acerbic side with a dry wit and the occasional joke. After only a few days at Dachau, his letters become unremittingly angry, embittered, and even paranoid. This transformation was the first signal—and a clue, really—to the man Wilsey’s children knew.

Of his commanding officer, he wrote:

one of the guilty, “caught” lazy officers of Pearl Harbor! You recall the condemnation that fell on the heads of those Honolulu Regular Army officers for too much luxury, ease, pleasure, comfort, unpreparedness, and lack of work. Well, he must have made a vow that never again would his Command even have the slightest chance of being observed to have-it-easy.

He had this to say about a colleague who confessed a wartime infidelity:

Em, I’m not a ranting Puritan preacher, a prude, a gossipmonger, or that general vein—but oh darlin’! ... You’d almost need someone to reconfirm the existence of marital fidelity’s existence in the world. … All outfits, including the 116th, have become so infidelitous it defies my adjectives to express it. ... I was so shocked/shaken/appalled that he would do such a thing that I just couldn’t get to sleep till 2 a.m. Granted! I could rationalize all night as to reasons why he betrayed his wife’s trust (liquor, war nerves, “escape.” Yes, it was Dachau escape—its psychic horror was a driving motive for escape of hundreds of Americans as much as anything) but I still would like to scream at him, “You damn fool; Look what you’ve done; it’s an irreversible something”!!

He criticized the military chaplain whose services he attended at Dachau:

Like so many chaplains, ours is just having a pleasurable-sightseeing (private jeep) looting/overseas interlude. In fact, in many ways he has almost assumed the “category” of a hypocrite—which has hand-in-hand brought with it a melerdramer in his sermons that I can hardly stand another Sunday. Yet back I go and sit there having my-own-service.

There was a lengthy screed about his black comrades-in-arms, which began with the always troubling disclaimer, “I am NOT prejudiced—whether you believe me or not”:

Racially and physical the negro male is 70+% a sexual athlete (to use sexologists’ phraseology). . . . As a result, the negro has had a 100% spree while overseas. . . . In fact, the British woman actually believes him to be an American-Indian, not realizing the marked racial, moral, endocrine and structural difference. . . . Now—we soldiers see/“see” an already developed “desire-for-white-meat” (intercourse with a white woman) in these negro soldiers; similar to an age-old American myth in certain white American men’s minds about sexual “super-ness” of the United States female octaroon.

Wilsey’s primary concern along these lines seemed to be that this interracial sexual profligacy might make its way back home:

I may be wrong, but it seems in my memory that you are normally, Christianly, and open-mindedly friendly with all Negros. My only thought (plus general rumors from state-side) is whether your normal, Christian, open-minded friendliness might be misconstrued by some post-overseas negro as being a “come on.” Now don’t get excited (or mad), dear. . . . (We do hear rumors (?) of an increase in white rapes by negros in the states—which would be most explainable via what we have seen for over a year(s) over here).

Wilsey even targeted the Dachau survivors:

After all our work in medical-filth, environmental-filth, and “psychic-filth” here at Dachau, there is a percentage of these patients (it would appall you) who are . . . not the least bit appreciative. . . . Why, Em, we could just scream!—and even God, I imagine, would say we were justified!

William Donahue from the Duke Center for Jewish Studies called Wilsey’s sentiments “unfortunately common for the day,” but also “helpful in challenging the typical narrative we trot out on these anniversaries about the Good Americans as the rescuers, liberators, and saviors. Many did brave and good things, to be sure, but they were also complex people with mixed motives—like all of us.”

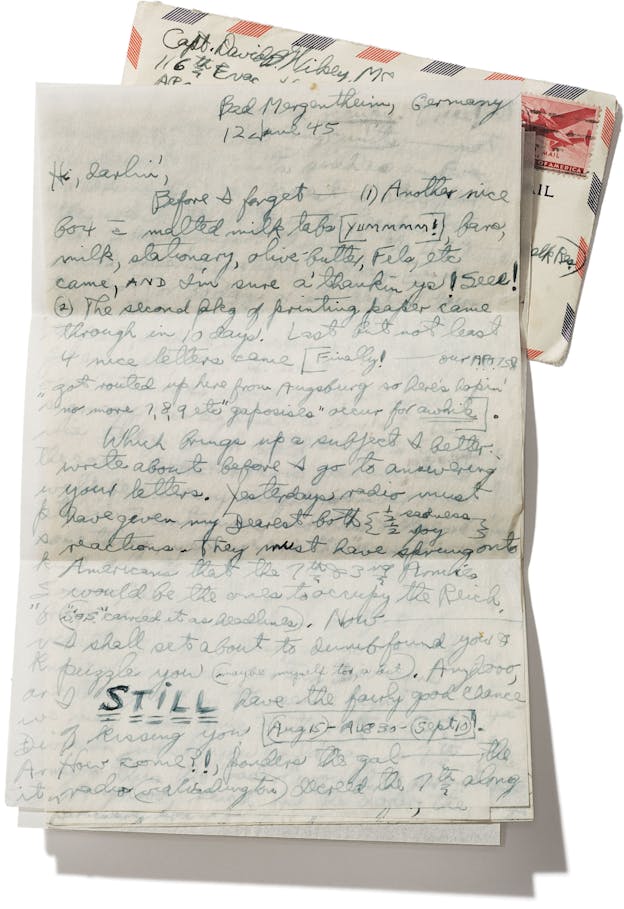

On June 2, the 116th Evacuation Hospital permanently departed Dachau “in a bouncing 6x6 truck,” heading to Bad Mergentheim, a small town about 160 miles northwest of the camp, for a period of R&R. Wilsey, instead of finding relief there, groused incessantly about how dull the setting was. He was grateful to have left “D—Damn Dastardly Dirty Dismal Den Dachau,” but only two days into his rest he was complaining that “most outfits have a decent, interesting place to do and see things—this place has nothing.”

Wilsey was aware, at least on some level, that something permanently altering had happened to him. On June 12, he wrote to his wife: “War and Dachau changes lots of things that you will have to just see for yourself.”

On Thanksgiving in 2009, Clarice, Sharon, and Terry Wilsey gathered at Clarice’s townhouse in Eugene, Oregon. It was the first time they had all been together since opening the trunk. Clarice again pulled out a few letters, and they sat around the table reading them. Clarice and Sharon wept. “He was an intense person, and it wasn’t an easy relationship,” Sharon said. “I felt kinda guilty that I didn’t make an attempt to be closer to him.” Terry, on the other hand, claimed that he doesn’t even remember the occasion. “I have never seen the letters,” he told me. “If someone had asked me an hour ago how many letters my dad had written to my mother, I wouldn’t have had the foggiest idea.” So unsentimental is he that he allowed the trunk to be sold at the estate sale for the Spokane house.

Wilsey’s children longed for an explanation for their father’s behavior their whole lives. And now, with the letters, they believe they had it. This was an experience both intensely satisfying and profoundly disorienting. Each one has reckoned with it in different ways.

Terry said he has little memory of his childhood, and preferred not to think much about it. “I wasn’t abused or anything else, but I just did not like [growing up],” he said. And yet Terry was a constant presence in the war letters. His father was overjoyed by every bit of information he received from Emily about their infant son, whom he affectionately nicknamed “Thump” because of how much he had kicked inside his mother’s womb. “Anyhooo,” he concluded an otherwise grim May 25 letter from Dachau, “rather than spout the truth for hours, let me close with a very pleasant thought—yet hard to express. Whenever I see ol’ Thump in a snapshot just a-workin’ away fixin’ or investigatin’ something, I just purr all over at his intelligent, cute, lovely, facial expressions. They are so nice. You must know and see better than I do.”

When Terry and I met in April, a stack of copies of his father’s letters sat on the table between us. He barely glanced at them. I tried to prod him by pointing out that he was a fixture in many of his father’s letters. He replied, “Am I?” and then changed the subject.

Sharon and Clarice hold equally conflicted views of their father and the meaning of his war correspondence. They were puzzled to discover the creativity, humor, and romanticism that Wilsey expressed in the letters toward their mother. To them, Wilsey was a deeply stern man who continually insulted their mother’s intelligence, and whose hair-trigger temper kept the household on edge. But the man who wrote all these letters was different. He was the sort of person who regularly sent their mother presents. He cracked jokes, praised Emily for her mothering skills during wartime, and most important, respected her enough to share his observations of the nature of people and war. In one letter, he wrote this apt coda for the Nazi regime:

Truth and totalitarianism just cannot coexist. One of the two has to die. For several hundred millions, totalitarianism did not die—so truth had to. And even the democracies have had to play that same way at times to help fight fire with fire. Even in the Army, bad results/happenings have innocently happened because of the democracies’ necessity for ignoring/suppressing the TRUTH. … So it results in my sitting in this world just screeeeaming sSShHHiiTT!

Sharon and Clarice never doubted their father’s love for them, and they were grateful that he was forward-thinking enough to insist they receive educations and pursue careers. (Sharon is an optician, Clarice a career counselor at a university.) But he had exacting standards and an often mercurial temper that made him nearly impossible to satisfy. The letters, Clarice told me, “helped me to realize that there was this dark, horrible experience he observed that he internalized and never processed. It probably contributed to his anger, his moodiness, his depression. I don’t know if it changes my memory, but it helps me to forgive him.”

Wilsey’s anxiety that people would not believe what he witnessed at Dachau began almost immediately, even before the end of the war. A week after leaving Dachau, on June 11, 1945, as the world’s attention moved to finishing the fight with Japan, Wilsey was already thinking of the legacy of the camps: “I know you ‘see’ and know it for what it was and that’s all I care. All I ask is that you instill it into as many thousand others as you can—till maybe we can get millions to ‘see’ it.” Two weeks later, he wrote her, “JUST JAM DOWN THEIR THROATS this sentence from unimpeachable sources: ‘When all other names are forgotten, Dachau will still be remembered.’”

In his lifetime, Wilsey was emotionally incapable or unwilling to revisit those memories. His daughters believe it’s now their responsibility to fulfill his mission. “Hearing about the uniqueness of these letters that he left behind,” Sharon said, “made me feel like, wow, even though he’s not here anymore, he’s still going to be able to speak for those people he served in Dachau.”

Correction: This article originally referred to the Dachau concentration camp as “KZ-Gedenkstätte-Dachau,” which is the name of the memorial located there.