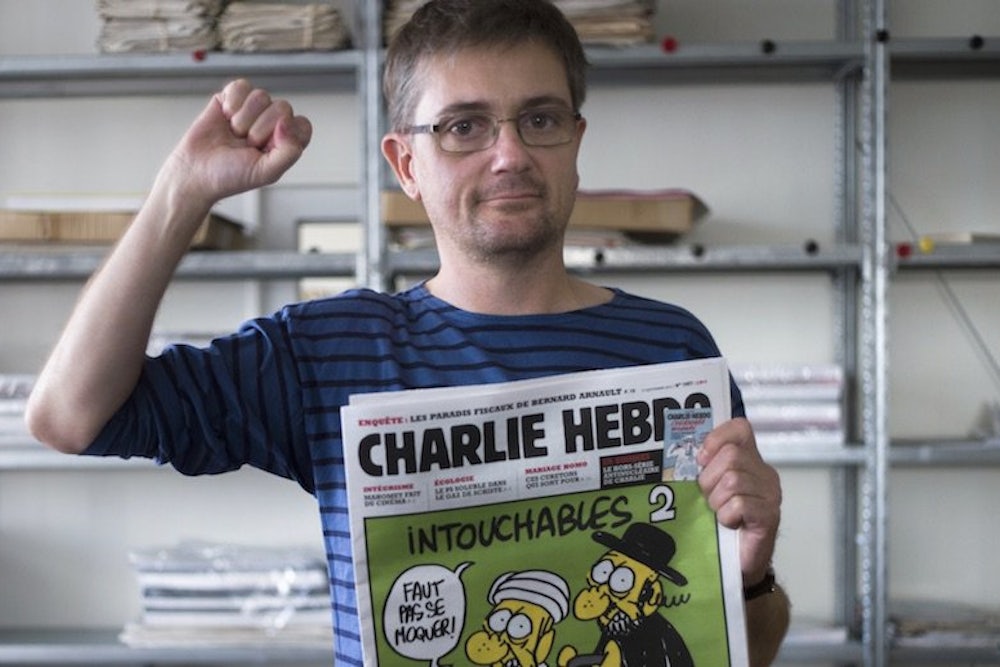

Over the last few weeks, the U.S. literary community has had an intense, divisive debate about a magazine that, until this year, almost no one in the English-speaking world had ever heard of, let alone read. The shouting match started after the PEN American Center decided to give the Freedom of Expression Courage Award to French weekly Charlie Hebdo, which suffered a terrorist attack on January 7 that left twelve dead.

In the wake of PEN’s award, two polarized camps have emerged. Opponents of the award—notably Francine Prose and Teju Cole—organized a boycott, on the grounds that Hebdo was a racist and Islamphobic publication which deserved free speech protection but not any prestigious laurels. In response, PEN and its allies have offered two major and contradictory arguments: that the award is for courage not content, but also that Hebdo cartoons in fact had an anti-racist intent.

Strangely, for a debate about a cartoon magazine, both sides of the Hebdo controversy ignore questions of visual style.

Implicit in the defense of Hebdo is the notion that cartoons that might seem racist to American eyes—notoriously, the depiction of the French Guiana–born Justice Minister Christiane Taubira as a monkey—are actually anti-racist when read with an awareness of context and intent. But this privileging of context and intent raises more questions than it answers, since it is entirely possible that a work of art with benign purposes might implicitly carry toxic messages. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was undeniably a novel with a strong progressive agenda: to discredit slavery. Yet it’s difficult to read the novel without cringing at the often patronizing way the slaves are portrayed, which is why “Uncle Tom” has become a byword for African-American subservience to white supremacy.

Intent is important, but not everything. Understanding the ruckus over Charlie Hebdo also requires awareness not just of the cartoons' goals, but of why their message often gets garbled—especially when images can be transmitted instantly around the world to societies unfamiliar with the particulars of French visual satire. The history of Charlie Hebdo can help explain both the magazine’s intent and also the cloud of hostility it generates.

Francoise Mouly, art editor at The New Yorker, is one of the few North Americans with a lifelong engagement with Charlie Hebdo. Mouly was radicalized as a teenager in her native Paris during the 1968 uprising. The anarchist monthly satirical magazine Hari-Kari, which spawned a weekly Hara-Kiri Hebdo in 1969, was a crucial part of Mouly’s political and aesthetic education. (Hara-Kiri Hebdo metamorphized into Charlie Hebdo in 1970). From the start, she found the cartoons in the magazine more interesting than the often wooly-minded articles.

“When I was young, I read Charlie Hebdo for the cartoons. I was shaped by their courage, and they had influence on me when I was a teenager—it was attached to history,” Mouly told The Washington Post. But being influenced by Hedbo doesn’t mean always liking it or being comfortable with its impudent humor: “When I was a kid, it made me terribly uncomfortable to read Charlie Hebdo. When I was a young woman, in the ’70s, they were taking on feminism. … Women were their main target. It was uncomfortable, not funny, raunchy and sexist stuff.”

On race and gender, Hebdo is very much a magazine of the 1960s counterculture, governed by a let-it-all-hang-out artistic strategy that often tries to combat prejudice by giving expression to it. The father of this approach was the comedian Lenny Bruce, who defended his use of the n-word on stage as a way of detoxifying the hateful power of the racist epithet. In his early 1960s routine “Are there any niggers here tonight?,” Bruce argued that “the word's suppression gives it the power, the violence, the viciousness. If President Kennedy got on television and said, 'Tonight I'd like to introduce the niggers in my cabinet,' and he yelled 'niggerniggerniggerniggerniggerniggernigger' at every nigger he saw, 'boogeyboogeyboogeyboogeyboogey, niggerniggerniggernigger' till nigger didn't mean anything any more, till nigger lost its meaning—you'd never make any four-year-old nigger cry when he came home from school."

Bruce’s appropriation of racism with an anti-racist intent was widely copied, not just by fellow comedians like Richard Pryor and Mel Brooks (who made liberal use of the n-word when they collaborated on the film Blazing Saddles), but also by the cartoonist Robert Crumb. Starting in the late 1960s, Crumb resurrected for shock purposes the sort of black-face imagery that had once been pervasive in American popular culture but which had become taboo when challenged by the civil rights movement in the 1940s and 1950s. Crumb’s “Angelfood McSpade” is a disturbing distillation of virtually every racist trope imaginable about people of African-descent.

Crumb’s work was almost immediately translated into French in the late 1960s and had a profound influence on cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo and many other publications. Crumb’s use of racism to fight racism was contentious at the time. Some fellow cartoonists, notably Trina Robbins, accused him of simply perpetuating racism. Others, like Art Spiegelman, thought that “Angelfood McSpade” initially worked for the desired end but that Crumb kept returning to the joke too often, so that satire became routine and lost its original intent. As Spiegelman told the Comics Journal in a 1995 interview, there are more intelligent ways to deal with racism than to keep saying the n-word in the Lenny Bruce manner and “for me that’s where the Crumb stuff is bankrupt in that that’s where it stops and that what it does. … If I could remake Crumb in my own image and make a different Robert Crumb, I’d probably cut out some of that shit.” Crumb himself largely abandoned this approach to race in the late 1970s, moving on to strips that took a more documentary approach to African American history.

The many-sided North American conversation over racist imagery has been far less developed in Europe. In part, this is because European civil rights organizations are both weaker than their American counterparts and less focused on issues of representation. Racist imagery, often with no ironic intent, is pervasive in European comics. Within that context, the ironic intent of Hebdo can easily get lost.

Almost entirely missing in the debate about Charlie Hebdo is any discussion of how intent and aesthetics might be at odds. Consider the notorious Charlie Hebdo cover showing pregnant Nigerian women captured by Boko Harem screaming “don’t touch our benefits!” At superficial glance, the cover might seem like a lurid display suggesting that African immigrants in France are welfare queens. A detailed exegesis from the blog Understanding Charlie Hebdo tries to refute the initial impression by noting that the real targets of the cartoon are wealthy French people, who were the ones making the complaint about a loss of benefits for large families. In effect, the aim of the cartoon is to say that these French whiners have a first-world problem compared to those kidnapped and raped by Boko Harem.

The problem is that even if we accept this interpretation of intent, it does little to address the overwhelming visual impact of the cover. The figures represented on the cover—drawn in a grotesque manner calling attention to their facial features—are not wealthy white Frenchwomen, but kidnapped and raped Nigerians. That’s the image that gets lodged in the viewer’s mind, whatever the purported message being conveyed. As often happens with Charlie Hebdo cartoons, the visual impact is very different than the intent.

Some might argue that the racist tinge of some Hebdo cartoons is a side issue. It’s not like the Hebdo killers Saïd and Chérif Kouachi were anti-racist activists. They were well-trained members of Al Qaeda who targeted Charlie Hebdo on the pretext of piety with the intent to polarize French society along religious lines. But this issue of polarization speaks to exactly why the racism is important. To the extent that Al Qaeda’s goal is to make French Muslims feel that they have no future in secular Europe, it’s worth asking whether Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons don’t, in their own way, further the alienation of the Muslim community.

The strategy of using racism to fight racism itself can be questioned. Juice that gave energy to Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor has turned sour after more than four decades. Charlie Hebdo is the French counterpart of Robert Crumb, but the magazine is a Crumb that has never changed or evolved, that keeps using in 2015 an artistic strategy from the 1960s. The real sin of Charlie Hebdo is not so much racism but arrested development, a grave aesthetic failure because political cartoonists have to keep up with times and be mindful of the impact their images have. The free speech rights of Charlie Hebdo deserve protection and the cartoonists who work at the magazine have more than earned an award for courage. It’s entirely possible to support Charlie Hebdo being honored even if you are uncomfortable with the magazine’s content. But we do artists no favor by refraining from merited criticism of their work. Charlie Hebdo cartoonists deserve to be taken seriously as artists, which means that the aesthetic failure of their anti-racist racism has to be acknowledged.