When eye-witness footage of a police officer shooting Walter Scott in the back made national news last month, the people of North Charleston, South Carolina, didn’t riot, and everybody who followed the story knows why. It wasn't because demographic or cultural factors distinguish the city from Ferguson or Baltimore—North Charleston has a large black population, high poverty, and a disproportionately white police force—but because officials there moved with alacrity. The mayor of North Charleston immediately announced murder charges against the officer, Michael Slager, who was fired the next day. The wheel of justice ground more finely than it would have without the video and more smoothly than it normally does when a law enforcement officer is under investigation.

There was no eye-witness video of Freddie Gray’s killing—only videos of him being dragged to a police van—and enough doubt surrounded the circumstances of his death that civil unrest filled the void. But just like in North Charleston, calm prevailed when Baltimore city prosecutor Marilyn Mosby announced felony charges against the officers who accosted and detained Gray. This is no coincidence. As The New Republic's Jamil Smith wrote recently, “[C]ity leaders and law enforcement need to learn that the real remedy to this kind of unrest is demonstrated action to stop police killings and brutalization.”

By its nature, a problem like police abuse—with systemic and acute causes, and systemic and acute effects—invites a multitude of proposed solutions, some of which are welcome, some of which are ideologically convenient, and some of which are both.

This latter category includes Ross Douthat’s recent suggestion that police unions have too much political clout and should be weakened. Douthat has ignited what promises to be an exquisitely awkward conversation, because the subject forces both liberals and conservatives to grapple with complementary inconsistencies. Liberals are generally solicitous of public sector unions, conservatives are generally scornful of them, and both make exceptions for law enforcement.

But if you want evidence for Douthat’s general thesis, you need look no further than this Tuesday article by his New York Times colleague Noam Scheiber, who reports on the local union’s predictably level-headed response to Gray’s killing.

“In Baltimore, the local police union president accused protesters angry at the death of Freddie Gray of participating in a ‘lynch mob,’” Scheiber reminds us. “The union, Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 3, has responded with open resistance to Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake’s proposals to make it easier to remove misbehaving police officers, and to give the city’s police civilian review board a ‘more impactful’ role in disciplining officers. The union also opposed the decision by Ms. Rawlings-Blake and Police Commissioner Anthony W. Batts to invite the Justice Department in to help overhaul the city’s Police Department after an investigation by The Baltimore Sun produced numerous allegations of police brutality.”

It’s plainly the case here that the union has placed the interests of its officers ahead of the interests of the public. And yet it’s also the case that focusing on the union is more useful as a means of prying open the door to a conversation about public sector unions in general, than it is as a solution to the problem of police committing violent abuse with impunity.

Weakening police unions would, among other things, eliminate the key political obstacles to outfitting law enforcement officers with body cameras and to demilitarizing their weapons arsenals. These are worthy goals, both of which might indirectly reduce instances of police abuse.

But the issue at the top of everyone’s mind isn’t exactly, as Douthat suggests, “the need to discipline, suspend and fire police officers who don’t belong on the streets— and the obstacles their unions put up to that all-too-necessary process.” It’s that the process by which most people suspected of assault or murder get investigated, charged, tried, and convicted has been completely corrupted when law enforcement officers are implicated.

This is where the specific comparison between police and other public sector unions falls apart. A teachers union might make it difficult to fire a teacher who doesn’t care about his students, just like a police union might make it difficult to fire a cop who’s lazy on the beat. But if a teacher were to, say, murder an unruly student in between classes, the union wouldn’t provide that teacher much protection from the legal system. If teachers were regularly tampering with evidence of physical violence directed against students, and prosecutors and grand juries were typically willing to look the other way when different evidence mounted, it’d be a little weird if parents tried to arrest the pattern first and foremost by weakening the teachers union.

Maybe they’d get to that eventually. But step one would be to break up the cozy networks that allowed teachers to commit violence with impunity—to change the system in a way that eliminated the almost iron-clad guarantee that teachers who instigate violent confrontations with students suffer no consequences. As Scheiber's article suggests, when criminal cops are accountable to the law, it circumvents the union power structure altogether.

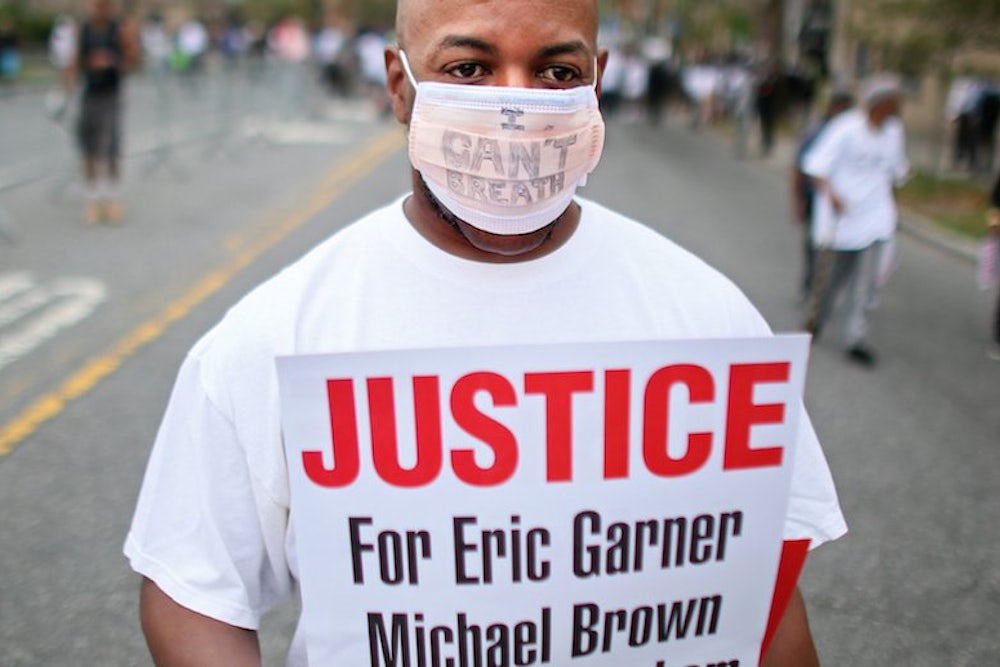

After the Staten Island officer who placed Eric Garner in the chokehold that killed him escaped indictment, I argued that communities afflicted by rampant police misconduct should organize to take authority for charging police, or for presenting evidence of misconduct to grand juries, out of the hands of local prosecutors and place it in the hands of uncompromised officials—special prosecutors or civilian review boards. Not every city and county will be able to elect a prosecutor like Mosby, and most probably don’t need to. But to the extent that prosecutors owe their careers to supportive police and depend on police to do their jobs, they shouldn’t be the ones tasked with investigating those police.

If police unions allow unindicted criminals to keep their jobs, they might deserve to be weakened, or they might simply have little recourse against abusive officers who are technically innocent because the system was never going to find them guilty. In either case, as a remedy for police abuse, weakening unions is a bit like bailing water out of a canoe when you have other tools at hand to fix the leak. Useful, perhaps, but slightly roundabout. Fortunately, most people don’t have strong ideological commitments to bailing water.