I first saw Orson Welles in December 1934 when he was 19 and I was 18. He was in the Katharine Cornell production of Romeo and Juliet in which he spoke the chorus and played Tybalt. I had never heard of him but knew at once that I would hear of him again: His presence was powerful, and his voice was already as rich as it ever became. A few weeks later I met Welles, for the first and only time, at the home of an Irish actor named Whitford Kane whom he had known in Chicago. (Seven years later all Whitford’s friends assumed that the naming of Welles’s first film was a private joke between the director and the older actor.) I was struck by the difference in the offstage Welles. The powerful young man seemed here more like an overgrown baby; the rich voice was frequently punctuated with high-pitched giggles.

This difference between the public Welles and the private Welles is much too pat to explain him. (Thompson, the reporter in Citizen Kane, says of Rosebud: “I don’t think any word explains a man’s life.”) Nothing that follows is meant neatly to categorize a multifarious career. But the difference that struck me at my one meeting with him was certainly in my head during all the 51 years that I followed his doings, and in general—impressionistically, at least—it seems to be relevant.

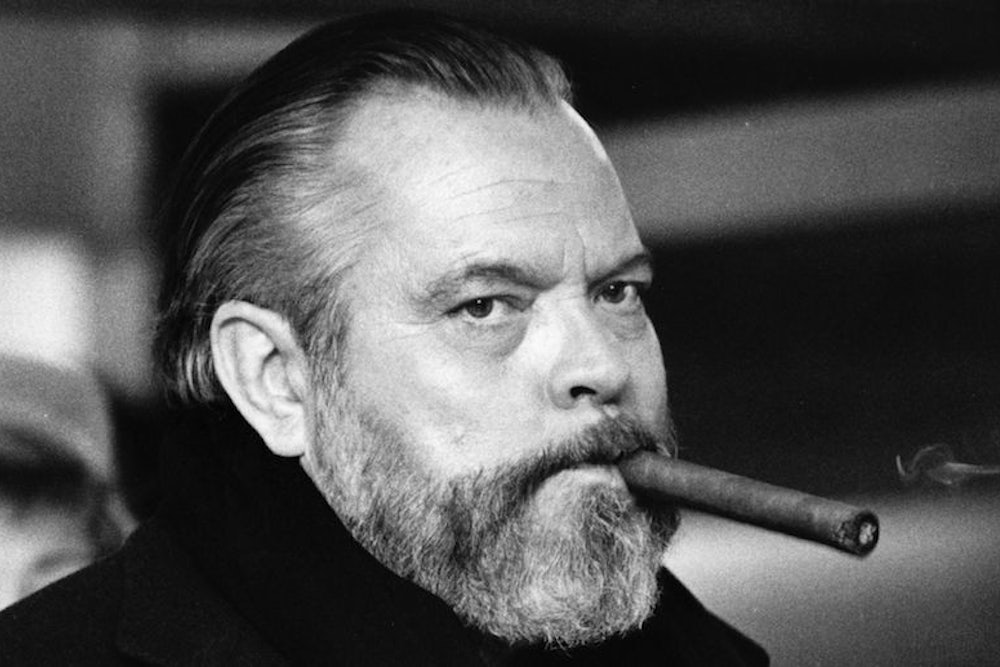

In his earliest years, the public Welles (in my terms) predominated: He went from strength to strength. I saw virtually all his theater productions in New York, most of which were, if eccentric, irresistibly exciting. In 1938 he did a good production of Shaw’s Heartbreak House and played Captain Shotover; and his picture was on the cover of Time, at the age of 23, in a white wig and beard. I heard very many of his radio productions, including the sensational War of the Worlds which were certainly the best radio plays in my experience.

In 1939 Welles went to Hollywood, and many of us, conditioned by the prevailing cultural hierarchies, feared that this was the end. Good-bye to the soaring genius. Our fear was heightened by the long delay in settling on his first film project and getting it launched. At last he made his film. (Between the finish of the film and its release, Welles came to New York and directed a dramatization of Richard Wright’s Native Son.)

Then in May 1941 Citizen Kane opened. No one who was not sentient at the time can understand the effect. Most of the people I now know grew up with Citizen Kane as a cultural fact, a piece of history, a locus of legend. But to be there when it arrived! Here was a young man who, after a pyrotechnic career in theater and radio, after a blazing rise to national prominence, had disappeared into Hollywood for almost two years as into a quagmire, and who emerged with an achievement that surpassed anything he had ever done. Not just a good film, not just (to this very date) the best serious American film, but (as many knew at once) one of the best films in world history. It was overwhelming. And he was just 26. Who could say what treasures lay ahead?

All this was the public Welles, as was The Magnificent Ambersons, even in the released version mangled by the producers, as was Macbeth, in Welles’s original version, lately restored. As was his exuberant 1945 Broadway production of Around the World in Eighty Days—Jules Verne set to Cole Porter songs, with Welles in several roles including a Chinese magician. (The show flopped, but sometimes I meet someone who saw it. Immediately we start to bore everyone else in the room by reminiscing about it.)

Still, through the early 1940s, the private Welles, the overgrown baby Welles, began to emerge (and, as later became clear, had something to do with allowing producers the chance to interfere with his films). Not long after the Cole Porter failure, he moved to Europe for tax and other reasons, and he remained there, with occasional return visits to work, for almost 30 years. Thus most of Welles’s life was spent abroad, as an acting-directing vagabond, without the rootedness and cultural continuity that, retrospectively, he seemed to have needed. In those years, increasingly showered with nearly indiscriminate praise especially by European rhapsodists, Welles allowed the self-willed, capricious baby in him to rule. Nothing that he directed ever lacked some touches that no one else could have approached, but films like Othello and Mr. Arkadin seemed to have a subtext of whim, almost petulance. He had always done as he pleased, but now his determination seemed childish conceit rather than artistic subscription. His acting, in his own and other people’s films, became casual and referential. (“I expect you to supplement my performance here with your knowledge of what I’ve done in the past and who I am.”) He was too talented not to give occasional good performances (The Third Man, Compulsion), but he was in a lot of trashy films, and in them as well as in better ones, he seemed invisibly to be sticking his tongue out at the world, telling it that he was going to do just as he liked.

At last he moved back to America, with the wayward child now buried in a grossly obese body. Here he added another color to his character, the genius whom Hollywood forgot, a la D. W. Griffith. He said he couldn’t find backing for the projects he wanted to make. He did shoot a good deal of a film called The Other Side of the Wind, and of course I wish he had been able to finish it, although the clips that have been shown are ambiguous. But he carefully prepared the role of de-throned king, the exile even when he was at home, and it served him juicily in TV commercials and talk show appearances. To me, those commercials and Falstaffian chats were horrible because of the gifts that he had. Not gifts that he had lost—I never thought of him, in terms of talent, as a “has-been”—but gifts that were still his and which, with that legerdemain of which he was so proud, he sometimes let us glimpse.

To have watched Welles through the years, to have seen his career as it happened, bit by bit, instead of in retrospect, was to become dourly aware of the Heraclitus tag: character is destiny. He was a man for whom everything was possible, absolutely everything, in the worlds of theater, radio, film, television. He could have been a major changer and shaper of our performing arts. But in the middle 1940s the spoiled child took over. He had overcome plenty of difficulties before then, but about that time he seemed to assume that the world now owed him a smooth path and that he would pay the world back for its refusal to pamper him by giving it only virtuosic arrogance.

Well, history will not witness the chronicle as it was registered year by year. The view will be retrospective, not serial. And that’s all to the good because immediacies of disappointment will dim, the heights of his achievements will dominate. History will care less than does a contemporary that Welles’s best works were bunched early in his career. Rossini, who died at the age of 76, quit operatic composing at the age of 37, and though doubtless many of his contemporaries were anguished or angry, history remembers only what he accomplished. Among Welles’s accomplishments, one is supreme. He made a film that changed film. Other directors—Griffith, Ford, Godard—have had sizable careers of immeasurable influence. But I can think of only two films that, in themselves, altered film vision. One is Eisenstein’s Potemkin, the other is Citizen Kane. In years to come, as the man and his life fade, who will care how old Welles was when he made it?