After the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that states could choose whether to accept Obamacare's Medicaid expansion, many red states opted to reject it—at great cost to uninsured patients and the financially stressed hospitals that care for them. Now, some of those states are reconsidering their decision, but want to expand Medicaid on their own, conservative terms.

Last week, Politico reported that in "nearly a dozen Republican-dominated states, either the governor or conservative legislators are seeking to add work requirements to Obamacare Medicaid expansion."

Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson told reporter Sarah Wheaton that Medicaid "is supposed to be an incentive and encouragement for people to work versus an incentive for people to just receive the government benefit and not be part of a working culture of Arkansas," while Governor Gary Herbert of Utah described his position this way:

I wanted to be able to say, ‘If you want the taxpayers to fund your health care, then you need to go out and be involved in a work program, no ifs, ands or buts.’ I’ve been accused by the Obama administration: ‘Well, you’re trying to turn this health care program into a work program.’ And I’ve said, ‘You’re right.’

Demanding a work requirement is a more radical view than simply opposing the Affordable Care Act. Restricting health insurance to those who are working or seeking work is inconsistent with not just the ACA but also with any other universal health insurance scheme, because universal plans cover everyone. This includes plans from Republican health care analysts who propose alternatives to Obamacare that also provide universal coverage.

There are five main problems with work requirements.

It’s not clear that a work requirement would significantly increase employment. Consider the group that becomes eligible for Medicaid under the expansion. The stereotype is that people who qualify for Medicaid don’t work, but actually most of them do. The Kaiser Family Foundation reports that

Nearly three out of four (72%) of the uninsured adults who could gain Medicaid coverage live in a family with at least one full-time or a part time worker and more than half (57%) are working full or part-time themselves.

As we will see later, some of those who aren’t working can’t work, so there is less room for improvement in the employment rate than many imagine.

Conversely, having a universal health care system doesn’t appear to create high unemployment. American unemployment is the same as in the U.K., Australia, and Canada. Unemployment in France and Italy is higher than the U.S.; in Germany and Japan, it's lower. All of these countries have universal health care except the U.S.

Having lots of uninsured people makes it harder to control infectious diseases. Uninsured people are much less likely to go to doctors when they’re sick. And if sick people avoid doctors, their illnesses remain undetected and untreated, endangering not only themselves but also those they encounter. For example, early detection and treatment of HIV infection greatly reduces the probability that an HIV+ person will spread the infection.

Why should Medicaid be tied to paid employment when other programs are not? People who have never worked can get Medicare if their spouse qualifies. When a homeowner takes a mortgage interest deduction on a tax return, he or she doesn’t have to prove that they’ve been looking for a job.

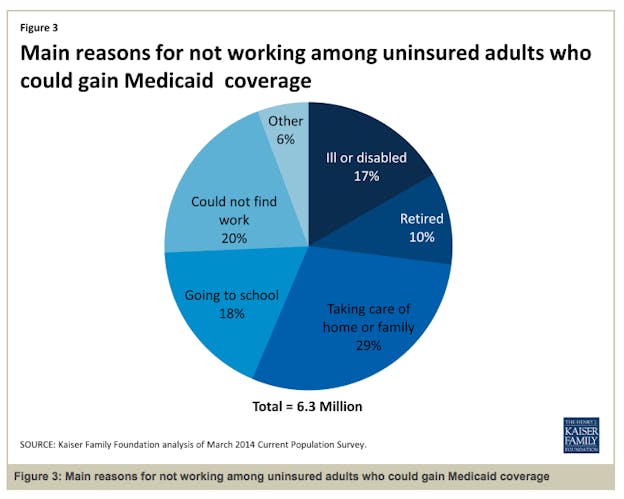

Work requirements will deny health insurance to people who work outside the labor market. The Kaiser Foundation surveyed adults who could gain Medicaid under the expansion. They asked those who were not working why they weren’t working. This chart shows the answers. Notice that 29 percent did not work because they were caring for family or others.

Some of these people will be parents at home caring for children. As Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig has pointed out, Ann Romney was celebrated when she asserted that being at home and raising her children counted as work. Is "working at home" a status that only rich women get to claim?

Others will be at home caring for an elderly or disabled family member, as home health care or a decent assisted living facility are too expensive for Medicaid-eligible people. For many families, a severe family illness requires at least one potential earner to leave the labor market. But a Medicaid work requirement means that if you leave your job to care for your relative, you give up your own health insurance. Shouldn’t that unpaid labor at least come with a health benefit? If a health aide works in your home, that counts as work. Why shouldn’t it count if you do it?

Finally, denying people medical care because they are not in the labor force is morally questionable. Let’s recognize that many supporters of work requirements believe it’s a moral issue—that the non-working poor are undeserving of this benefit. Many otherwise good-hearted Americans hold this view, but few non-Americans agree. The only developed countries that do not provide universal health care are some fragments of the former Yugoslavia, Belarus, and the United States. Elsewhere, people hold the view that respect for human dignity requires that everyone have access to a decent minimum of care.

It is particularly hard to understand how Christian governors would view a work requirement as moral. There are more than 40 episodes of healing in the Gospels, comprising about one-third of the text. Jesus heals anyone who asks, and it should go without saying that he never asks whether the petitioner is working. As John Paul II wrote in the encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (The Social Concerns of the Church), we must "embrace the immense multitudes of the hungry, the needy, the homeless, those without medical care and, above all, those without hope of a better future. It is impossible not to take account of the existence of these realities. To ignore them would mean becoming like the 'rich man' who pretended not to know the beggar Lazarus lying at his gate."