Shortly after boarding an Indonesian domestic flight, the voice of an air-stewardess will flood the intercom, sweetly informing you, in Indonesian and then again in broken English, that the penalty for transiting drugs is death. When you arrive at the airport in Jakarta, you will pass under a crimson banner that announces, “Welcome to Indonesia, Death Penalty for Drug Traffickers!”

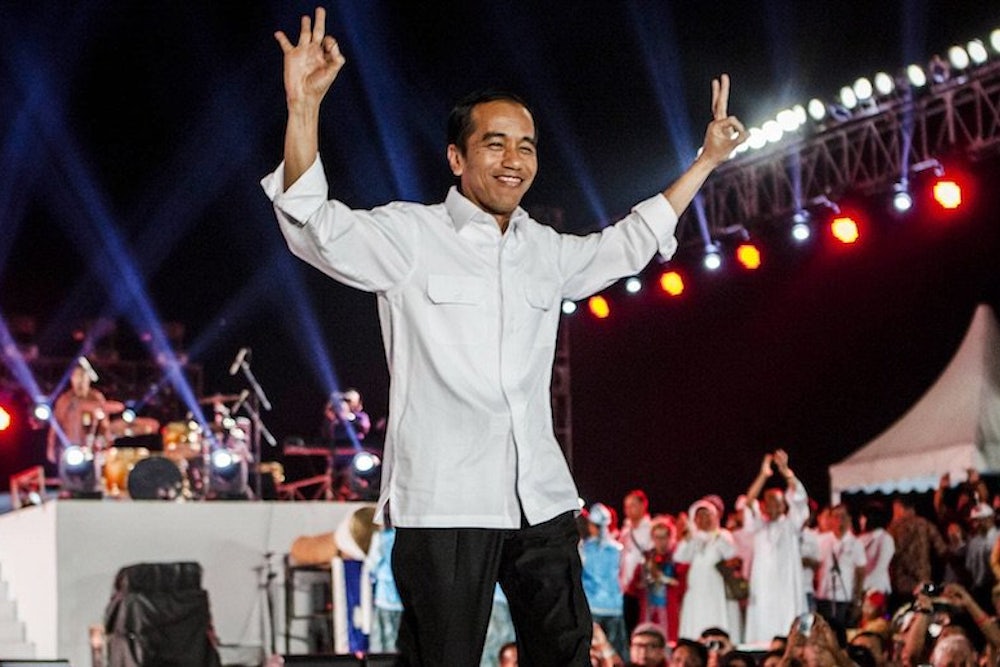

But when Joko “Jokowi”Widodo, Indonesia’s reformist new president, was inaugurated last October, it was not clear whether these warnings were still current. His predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, had executed people sparingly, even placing an unofficial four-year moratorium on executions during his second term. As a result, when Jokowi took office, there were as many as 65 convicts on death row for drug offenses alone, including an estimated 45 foreigners.

Yudhoyono had been criticized in the Indonesian press for bowing to foreign pressure and commuting the sentences of foreign drug traffickers. Eager to distinguish himself, Jokowi declared shortly after assuming office that there was a “national emergency” surrounding drugs—which, he claimed with little evidence, took 50 Indonesian lives a day. His administration insisted that only the death penalty would deter drug traffickers. Three months later, in January, Jokowi proceeded with the first wave of mass executions; six drug offenders, including five foreigners, were killed by firing squad.

Just after midnight Wednesday morning, eight more drug offenders were executed. Of those, the highest profile were a Brazilian man with paranoid schizophrenia who, according to his pastor, went to his death unaware that he was being executed, and two Australian men whose impending deaths inspired nationwide vigils back home and an extraordinary public campaign to have them freed (the duo had admitted to trying to smuggle 18.5 pounds of heroin). In a video titled, “Save our Boys, Mr. Abbott,” a series of Australian celebrities had demanded that Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbot find a way to bring Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukamaran home. “Tony if you had any courage and compassion you’d get over to Indonesia and bring these two boys home,” said one. “Show some balls.”

The executions have turned into a diplomatic nightmare for Indonesia, whose new president has been working to stimulate Indonesia’s lagging economy by encouraging foreign investment. Australia withdrew its ambassador—the first time it had ever done so over citizens executed abroad—and promised to re-evaluate its relationship with the country. Brazil expressed anger but it didn’t have an ambassador to pull, as its ambassador had already been recalled after the first Brazilian trafficker was executed in January; the government said it would delay the return of its ambassador to Jakarta. Ban Ki-moon, secretary general of the United Nations, pleaded with Indonesia to commute all further capital sentences. (There are still 33 foreigners on death row for narcotics offenses.)

“Jokowi did not expect the other nations to protest this hard,” said Yohanes Sulaiman, lecturer in international relations at the Indonesian Defense University. “He was caught completely off guard.”

And yet, on Thursday morning Indonesia announced its next wave of executions.

Indonesia’s attorney general, HR Prasetyo, dismissed the international pressure, promising that the diplomatic fallback would be merely a “ripple.” “It’s the diplomatic domain, there will be a solution,” he said. Indeed, the domestic pressure may be greater. A poll from Kompas newspaper showed that 86 percent of Indonesians support executing the Australians. It will be difficult for Jokowi to back down now. “From what I have heard,” Sulaiman said, “the debate now in the Palace is, ‘If we stop the executions now, then we bow down to foreign pressure.’ So I think the government will keep pushing forward with [the executions], that’s my gut feeling. But I am not sure they have a plan to deal with the international fallout.”

The run of negative stories looks to continue, as the French Foreign Affairs Ministry declared it was “mobilized” over the case of Serge Atlaoui, its citizen on death row, and international media has begun focusing on the British grandmother who worried that she would be executed next. The one slightly optimistic story of the week—the last-minute halt to the execution of Mary Jane Veloso, an impoverished Filipino maid—also turned sour. Jokowi insisted that Mary Jane’s execution was only being delayed to allow her to testify in a new court case. It would not be cancelled, despite the Filipino president’s personal appeals.

Andreas Harsono of Human Rights Watch says Jokowi is under intense domestic political pressure to continue with his current course, and that the BNN (the national narcotics agency) and the attorney general “are for moving forward.” Indonesian politicians, meanwhile, have used the opportunity to posture against what they portray as countries eager to encroach on their sovereignty. Tjahji Kumolo, the minister of Home Affairs, said in March: “If there were a thousand Tony Abbotts it wouldn’t be an issue. Whoever it is—a thousand secretary generals of the U.N., a thousand prime ministers—Indonesia is a sovereign nation.” Jokowi repeatedly warned nations not to interfere with Indonesia’s sovereignty. After the executions, Jokowi repeated, “It’s the sovereignty of our law.” His vice president was even more scathing of foreign governments' objections, saying of Australia, “We import more from Australia so if there is any freeze in trade relations, it would be their loss.” Tobias Basuki, a researcher at CSIS, a prominent Jakarta think tank, wrote in an email that there has been a “harsh and hyper-nationalistic narrative along with the executions… Indonesia and Jokowi in particular has lost much respect and moral standing.”

The international pressure may have had an effect, however slight. The next group to be executed consists of five Indonesian men convicted of murder, rather than foreigners convicted of drug trafficking. Some speculate that the decision is meant to show the Indonesian government’s commitment to following through with executions but without further alienating any foreign powers. According to Harsono, “The heat from the international outcry and the fact that it is against international law to execute drug traffickers,” may have prompted the Indonesian government to “go domestic and to pursue murderers.”

On Thursday, I spoke with Todung Mulya Lubis, a lawyer and longtime campaigner against Indonesia’s use of the death penalty, who represented the two executed Australians. He said that it was “possible” that the execution of Indonesian murderers, rather than foreign traffickers, was a sign that the government was reconsidering, but added, “I cannot say that. It remains to be seen. It may just be that the other cases [of foreigners] are still [requiring] legal action.”

Australian media focused relentlessly on its government’s efforts to save Chan and Sukamaran. When it was clear they would be executed, the Australian press meticulously documented their final days, from Chan’s last-minute marriage, to Sukaraman’s final self-portrait, where he depicted himself with a hole in his chest, to the moment the two were led out of their prison, given the choice to stand or kneel, and shot through the heart.

After the executions, Lubis tweeted:

I asked him how he was feeling.

“How do I feel? Gloomy, is the feeling that I have. I have never been so stressed, so depressed, with what’s going on. Because I expected humanity would prevail. I expected a sense of justice. But that is not the case.”

Correction: Because of an editing error, a previous version of this article stated that eight of the Bali Nine were executed, and that Mary Jane Veloso was the one spared. Only two of the Bali Nine were executed, and Veloso is not a part of the Bali Nine.