You know Hillary Clinton’s voice, right? I mean, you know it. It’s just so loud and annoying. Or maybe it's like a nagging wife. Or inauthentic—that phony Southern accent! Those flat Midwestern vowels! Whatever it is, her voice is burned into your brain.

Now think of Jeb Bush’s voice. It’s so—wait, what does it sound like again? He sounds just ... like a guy, maybe? It's probably hard for you to recall distinguishing features about most of the Republican candidates. Maybe you don’t know what Ted Cruz sounds like, except that he sounds like a jerk. Why? In part it's because women’s voices are scrutinized more. It's also because Clinton has been in the public eye for far longer. The conventional wisdom about Clinton's character has fully matured, but it's still forming for her potential Republican competitors, like a cicada grub nestled underground. Despite our collective sexist tendencies, the Republican candidates' voices will eventually get some attention.

A politician's voice shapes how we see him. Take, for example, Lenny Bruce’s early 1960s imitation of Lyndon Johnson. "They didn't let him talk for the first six months," Bruce says. "It took him six months to learn how to say negro." He imagines handlers trying to teach Johnson to say “negro,” but the sound of the n-word keeps slipping through. In frustration, Bruce-as-Johnson yelps, "I cain't hep it! I cain't say it! ... Lemme show mah scar." Johnson had a reputation as crude and uncultured. Of course, he went on to sign landmark civil rights laws.

Mike Huckabee, who is considering running for president again, has a new-ish campaign book called God, Guns, Grits, and Gravy in which he divides America into two groups: the “Bubbles,” who are haute-lettuce-eating college professors in cities on the coasts, and the “Bubbas,” who are the real Americans. If you thought the broad theme of the 2004 election—John Kerry as elite fancypants, George W. Bush as rugged manly man—was too sophisticated, then this book’s for you. While it may lack new political insights, Huckabee’s book offers a framework for analyzing the candidates’ speaking style, says Carmen Fought, a Pitzer College linguistics professor. Fought studies how we use language to project identity, which is what these candidates, especially the less well-known Republican field, are doing as they introduce themselves to voters.

“The candidates are kind of splitting up the Bubbas/Bubbles thing,” Fought says. Bubbles have an unmarked dialect—"anything regional has kind of been educated out of you” in college. Bubbas, as the name implies, have regional accents. A big difference is how much emotion the two groups show with their pitch range—how high and low your voice goes. “We associate pitch range with being emotional,” Fought explains. You don’t say your grandmother died in same flat way you’d order a sandwich.

So while Bubbles moderate their speech, because we associate them with being rational and therefore less emotional, “Bubbas are emotional, they have feelings about things, which is funny because it’s like a male stereotype.” A smaller pitch range is associated with being more formal, a bigger one with being more casual. Though he may not have all the same political positions as a bubba like Huckabee, Fought says, “Rand Paul is the most Bubba of them all. White, Southern—he speaks with a lot of emotion." Of the candidates Fought looked at, the Bubba-to-Bubble spectrum goes like this: Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Hillary Clinton.

Rand Paul: Super Bubba

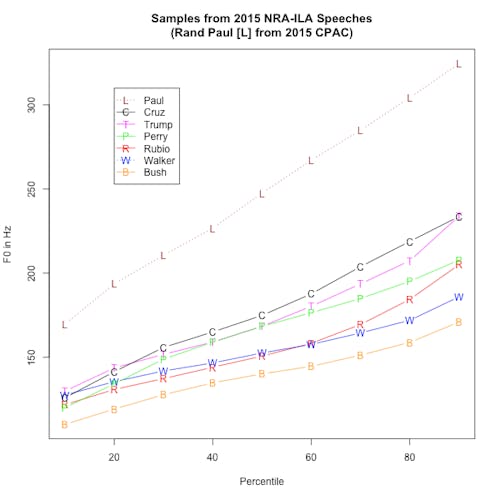

University of Pennsylvania linguist Mark Liberman analyzed the first minute or so of the Republican candidates' speeches at the National Rifle Association conference this month. (Paul didn’t speak at that event, so Liberman used his CPAC address from February.) The striking results are in the chart below. "Apparently in pitch range, as in other respects, Rand Paul is sui generis," says Liberman, who runs the popular linguistics blog Language Log. "Unless for some reason the atmosphere of CPAC creates strikingly shriller voices…"

[A quick note on how to read these charts: The y-axis shows pitch, the x-axis shows how much of the candidate's speech is at that pitch or below it. For example, in his NRA speech, 10 percent of Donald Trump's pitches were below 129.9 Hz, and 90 percent were below 233.9 Hz. The higher the line, the higher the voice (in the sample measured). The steeper the slope of the line, the larger the pitch range.]

Fought says Paul is in "the position with the most flexibility" because he's a white guy, and we expect politicians to be white guys. Politicians who are not white and male see their actions analyzed based on their minority status—e.g., President Obama did X because he’s black. If Hillary Clinton says she "kind of thinks" something, that might be interpreted as a sign of indecisiveness, whereas if Jeb Bush says the same thing, it would pass unnoticed. So, Fought says, Paul "has a full-on Southern variety." (Paul, born in Pittsburgh, was moved to Texas when he was 5.) "He’s very emotional, and what he’s trying to convey is that he’s a good ol' boy just like you.”

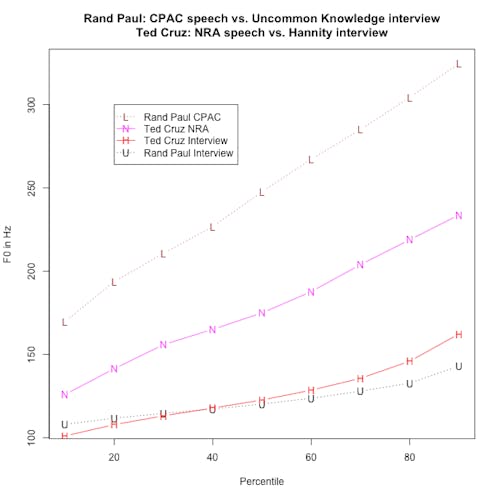

In interviews, however, Paul's voice shows far less emotion. In fact, he drones.

Stanford University linguistics professor Penelope Eckert says that in interviews, Paul almost looks as if he has lockjaw. “He hardly moves his mouth at all," Eckert says. "There’s something very uptight about the way he talks.” This chart, also by Liberman, compares Paul’s and Cruz's pitch ranges in delivered speeches and in interviews.

Why the huge gap? Is it because Paul is nervous speaking before a crowd? Probably not, Liberman says: “He doesn't sound like he's nervous. He sounds like he's yelling, essentially. A really high level of physiological arousal, real or simulated.”

To be clear, this is not an analysis of the candidates' authenticity, of whether they're presenting their true selves in interviews and speeches. Our speech naturally changes over time and in different settings. Sarah Palin dropped a lot of Gs—runnin', goin'—as a young sports broadcaster, explains Geoffrey Nunberg, the linguist contributor for NPR's "Fresh Air with Terry Gross." By the 2008 campaign, Palin was dropping Gs more strategically. And that's okay! "There is an idea of authenticity that somehow an authentic accent is the one you had when you were 16 and you woke up in the middle of the night," Nunberg says. People refashion their speech and language all the time. "Authenticity is… in a sense it’s a bogus notion, I think, in these contexts."

Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz: Similar Stories, Different Sounds

The Republican Party has explicitly said it needs to reach out to Latino voters. This year, two Latino Republicans have already declared for the race. Neither plays up these roots in his speeches. For a guy who was born and raised in Miami, Rubio has "very unmarked" speech, Fought says. He sounds like he just came out of the halls of Harvard. "He speaks very formally, not emotional, not a lot of ups and downs," Fought says. No Southern accent, and certainly "nothing we could interpret as a Spanish accent. Which, he wouldn’t have that, growing up here. But he could fake it, which people do."

Cruz was born in Canada, and similarly to Paul, moved to Texas when he was 4. He's more Bubba, Fought says, in that he shows more Southern features, more emotion, less formality, than Rubio. Compared to Paul, Cruz is Southern Lite. (Of course, it is Cruz who went to an Ivy League school, and was reportedly quite snobby about it, while Rubio got his bachelor’s from the University of Florida and his law degree from University of Miami.) Here's how Rush Limbaugh described Cruz after he announced his presidential candidacy: "And here comes Ted Cruz saying: 'I'm one of you, and I know that you are an army out there waiting to be mobilized, and that nobody has asked you to join them in a number of years, and I'm here to do it today.'"

Fought says the differences between Cruz and Rubio owe partly to their reading of the electorate. Latino people come in all shades of skin tone, she says, but in this country, Rubio physically looks more Latino than Cruz. Rubio also looks much younger than Cruz, even though he's less than six months younger. That puts Rubio "in a little bit more precarious position." He's trying to project competence, Fought says, citing similarities to the styles of Clinton and Obama. It seems to be working. Here's how The Des Moines Register editorial board described Rubio after an in-person meeting: "While he could be self-effacing and conversational, Rubio exhibited an impressive grasp of public policy detail. He held forth extemporaneously on a broad spectrum of issues that included the economy, immigration, health care, education, energy..."

Jeb Bush: Maybe Bored?

Jeb Bush also has to project competence, for a different reason. Have you noticed Jeb doesn't sound much like George W.? "There is absolutely no historical or biographical reason why George Bush and Jeb Bush should sound different in terms of their voice or their accent," Fought says. Though the way we talk can change as we grow older, for the most part, we pick up our regional variety as kids. Jeb and George sat around the same dinner table in the same Texas house and got the same education. "It’s not like one stayed home and ran the farm and one went to college," Fought says.

There's an upside to being a guy people can relate to. George W. Bush was famously the candidate voters would like to get a beer with, but given that he left office with rather low approval ratings, Jeb needs to distance himself from his brother's persona. Here's Fought's take:

So what is Jeb Bush doing? He’s trying to present both. He’s like, "I’m a regular guy, but not as regular as my brother. I’m Southern and I’m friendly, but I’m not that Southern, so don’t think I’m dumb. If I want to I can tell jokes and be a regular guy but I can also talk and sound like I’m pretty educated. I don’t use a lot of emotion in my voice. I’m not that kind of Bubba—I’m like an educated Bubba, so don’t mix me up with them.

Bush might be going too far. Liberman said of his pitch range chart, "I don't think this means that Bush is manlier, but rather that he's less worked up." Likewise, Fought says, "He’s holding back on that emotional pitch thing so he doesn’t sound like a Bubba and so he’s the smart Bush or whatever—he’s holding back on it so much that he may go too far and sound bored to people." She wouldn't be surprised if a pundit or a rival criticizes Bush for not wanting to be in the fight.

Hillary Clinton: Female

That brings us to the over-scrutinized voice of Hillary Clinton. To pull one recent example, here's a New York Times reporter analyzing Clinton's presidential campaign announcement video last week: "It allows her to use her quieter-but-confident speaking voice, instead of the VOICE she uses at news conference and at rallies, when she sometimes SPEAKS SO LOUDLY in hopes of conveying ENERGY and FORCEFULNESS (rather than simply projecting her voice better)." Bloomberg Politics has broken down Clinton’s accent as it has changed since 1983, as she moved from Arkansas to Washington and spoke before different audiences. The reporter felt moved to assert three times that Clinton’s changing accent was not a sign of inauthenticity.

First, it’s important to note that women’s voices generally get more scrutiny. (Sample shaming trend piece: a 2006 New York Observer story headlined, “City Girl Squawk: It’s Like So Bad- It. Really. Sucks?”) Vocal fry, the subject of countless trend pieces and Today show segments in the last three years, is supposedly the terrible thing young women do to their voices to sound like dumb sex kittens. Remember uptalk? Before vocal fry, uptalk was the scourge of American English, in which young women would end declarative sentences with rising sounds as if they were asking a question. (As Liberman titled a 2005 Language Log post about uptalk, “This is, like, such total crap?”) The thing is, these things weren’t really new, and they weren’t exclusive to women. Here’s George W. Bush using uptalk. Here he is using vocal fry.

“There’s an idea that men and women talk differently, that men are from Mars, women are from Venus," Fought says. "That’s really misleading. The biggest differences is in how men and women are perceived, and our ideas about how women should talk and how men should talk.” Men are supposed to be assertive, loud, and competitive. Women are supposed to be soft-spoken, cooperative, and helpful. “No matter who’s saying something, a man or a woman," Fought says, "they’re being judged on their language via their gender.”

Hence the extreme scrutiny for a woman politician's voice. A fascinating anthropological document is a 2008 video of Republican pollster Frank Luntz explaining Clinton’s voice to Sean Hannity on Fox News. A clip rolls of Clinton speaking in a lecture hall with reverberation that wrecks the audio quality. Of course Clinton sounds awful. Luntz says, "Forget the words. Listen to the way she communicates. It's ALL AT THE SAME LEVEL AND I DONT WANT TO MAKE YOUR CONTROL ROOM GO NUTS BUT IT GETS LOUDER AND LOUDER but her voice doesn't go up or down." Then Luntz looks like a little boy about to tell a dirty joke: "Her voice is ... and we'll end up getting hit by Media Matters, but it's true. In the research I have done ... her voice turns people off. Because they feel like they're being lectured." This clip exists on YouTube as "Hillary Clinton's Voice is a Turn Off!"

"I don’t know that the best evidence of the effect of Hillary’s voice would be in a recording of her giving a speech over a PA in a reverberating hall, captured on a cell phone, rebroadcast over TV and then recaptured on cell phone,” NPR linguist Nunberg says.

If you watch old clips of Clinton from the 1992 campaign, she is presenting herself in a much more feminine way, Fought says. She sounds more emotional—even if that means being pissed off when reporters ask about Gennifer Flowers. She sounds a little bit more Arkansas. She even wears a headband. But not anymore. "I think the advice she’s gotten is to get anything marked out of her speech," Fought says, "anything that people can pick up on and make fun of." It's not masculine of feminine, it's not regional, it's not overly emotional or overly assertive. Hillary Clinton, having learned some lessons from the 2008 presidential race, might be playing up her femininity, talking about weddings and yoga and babies. But when you hear her voice, she doesn't want you to think "girl."

And this helps explain the Times reporter's analysis. Clinton is—and this would surely delight her fellow Arkansan Huckabee—a Bubble. Fought says:

No emotion, no ups and downs. All she does to emphasize her speech, instead of using those emotional pitch range changes, she uses an emphasis on stress patterns. ... Because emphasizing words is not as associated with emotion as pitch changes. So she’s using that instead. But she doesn’t do a lot of ups and downs. Because she’d be labeled as an emotional woman. ... She’s projecting, "I’m an unemotional expert who’ll solve your problem."

Clinton "has a loud and clear voice," Stanford linguist Eckert says. "A ‘nice’ woman tends to have a breathy voice," she explained, sounding a little Marilyn Monroe-ish. "There’s nothing breathy about Hillary Clinton’s voice. And if somebody doesn’t want a woman to be powerful they’re not going to like that voice."

Nunberg agrees: "People have become so conscious of the semi-coded ways in which people communicate these sexist notions of aggression." Like Frank Luntz noting he would get "hit" by Media Matters, for example. "Voice will be the place where that comes home to roost. ... It’s just another way of saying ‘shrill.’"

People who do not like that voice really do not like that laugh. Last June, National Journal compiled "The Comprehensive Supercut of Hillary Clinton Laughing Awkwardly With Reporters." The same month, the Washington Free Beacon created "Hillary Clinton's Interview Tour: A Laughing Matter | SuperCuts #70." Here's Jimmy Kimmel's 2008 roundup of Clinton laughing, which a YouTuber has called the "Hillary Clinton laugh and cackle comedy compilation dvd." Here's "The Daily Show"'s from 2007, featured on CNN's "Reliable Sources." (National Review writer Jim Geraghty says, "Did anyone else's eardrum just burst in pain after hearing that over and over again?") The New York Times called it "the Clinton Cackle."

"Laughter’s weird," Nunberg says. "If you listen to somebody laughing it always sounds weird. Everybody’s laugh sounds insincere if you play it more than once." Eckert's view of Clinton's laugh is a 180 from the media's. "She has a real laugh. Whether it’s forced in those situations or not, she has a real laugh." It's not a girlish giggle. It's not a chuckle, which for a politician is rare, she says. "There’s something very fresh about that laugh. She maybe be forcing herself to think that something is funny, but to me it’s a good laugh." It's like her clear, loud voice, Eckert says: "She’s putting herself out there. She is not softening anything for anybody."