The first New Republic I recall seeing erased me. I found it in my local public library during my junior year of high school; the edges were a little bit tattered. The magazine had put a blond, white teenager wearing headphones on the cover and called him “The Real Face of Rap.” People had been reading this, I realized, and I felt acid in my throat. The kid’s expression in the cover image hinted that even he was surprised. The boldness of the contrarian image and the declaration seemed intended to injure. And the article it introduced was not merely ignorant. It bludgeoned me with its wrongheadedness. Not only did I feel that the magazine wasn’t for me: It actively sought to invalidate me.

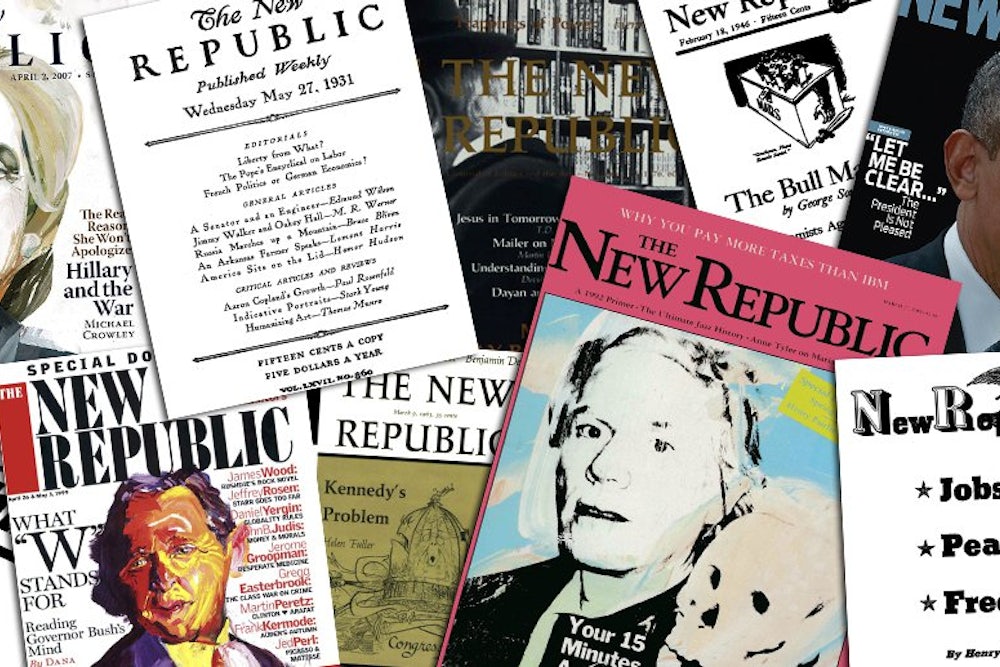

This was hardly an isolated incident of cultural insensitivity or obtuseness, as Ta-Nehisi Coates reminded us last December. The New Republic archives are rife with it, from an issue devoted to The Bell Curve to Stephen Glass’ inventions to the unconscionable bigotry against Arabs written by former editor Marty Peretz. But by the time the magazine, now my magazine, published its own examination of its racial legacy in February, it seemed to me that things had changed, and I had taken a job here as a senior editor.

I bring all this up because of the discussion that has arisen among readers since the publication of a Michael Eric Dyson essay about Cornel West on our site this past Sunday. The conversation has been wide-ranging, but for me, there has been one stinging question that must be addressed: Why, considering this magazine’s history of a white gaze and a white audience, did it appear in The New Republic?

I first saw that question in a post on my Facebook wall the night we published the essay, which I co-edited with my colleague Theodore Ross. Lamenting the harshness of the critique and the public manner in which it was delivered, author and Vassar professor Kiese Laymon directed this question at Dyson on Facebook: “You do this in the New Republic? This? There? Why?”

Those questions have a very simple answer: because I work here. Dyson, who I’ve known since I was a producer at MSNBC, had been working on the essay for several months. When he learned from my former colleagues that I had changed jobs, he contacted me in March and asked whether we’d consider publishing his essay. I was well versed in the hyperbolic vitriol West had directed not just at President Obama and Dyson, but also at Melissa Harris-Perry, the host of the show on which I’d last worked. Not only did I agree that a forceful response to West was long overdue, but that it should come from a fellow black intellectual. We accepted it.

I detail all of that not to defend Dyson or the essay, neither of which need it, but because others have asked, with varied intent, why it ended up here. I also offer the facts to contrast the hypothesis Jason Parham offered in Gawker. Parham wrote that the reason Dyson’s essay appeared in the magazine was “because The 100-Year-Old Magazine of Things White People Think is doing what it has done many times throughout its storied past: treating blackness as a thing to be picked apart. Only this time, they had another black man do the bidding.”

In fact, the magazine’s racial legacy was one reason why I considered it vital that we publish “The Ghost of Cornel West.” Essays like this explore black humanity with an intensity that has rarely been seen before in the pages of The New Republic. But the responses of people like Parham seem not only question the story itself, but whether our publication had undermined our stated commitment to stories and ideas that do not simply “represent the views of one privileged class, nor appeal solely to a small demographic of political elites.” Or, put more simply, that this remains a magazine purely of and for rich white folks. Those days are over.

This is not simply a matter of head count. Yes, I and several other colleagues of color have upped the melanin quotient of the magazine’s editorial staff significantly, and we expect that trend to continue. Of greater importance to me, however, is a more widespread problem that continues to arise in our dialogues about race. Too often we continue to frame disagreements about race as a form of betrayal, and seek to erase our enemies, or even those who merely disagree with us. When “The Real Face of Rap” cover was published, I was fending off insults of “Oreo” (black on the outside, white on the inside) from fellow black students. Today I stand accused of having been swallowed up by an encompassing whiteness as a consequence of where I work.

One of the most peculiar responses that I have fielded since Sunday night was a tweet: “By the way, why are you at The New Republic?” I’m here to inspire debate, and to do quality work. I’m also here to make sure I’m a part of ensuring that The New Republic will never be the same magazine I saw in my local library as a teenager.

That won’t happen overnight. It’s already evident, though, in the increased frequency of stories and perspectives offered, from staff and contributors, that reflect the realities of people of color. Articles like Parham’s, I’d argue, are incorrect because they inflict on me and my colleagues what that 1991 New Republic cover did to entire communities: Erasure. Criticism in any debate is welcomed and necessary. But it never should include decolorization. My blackness is essential to my identity. Deny it, and you deny me. At The New Republic I am trying, with my presence and our work, to make sure no one is similarly denied, and to reflect the lives of all people. If you don’t like what we do, cool. But erasing the humanity of those with whom you disagree is no way to offer critique.