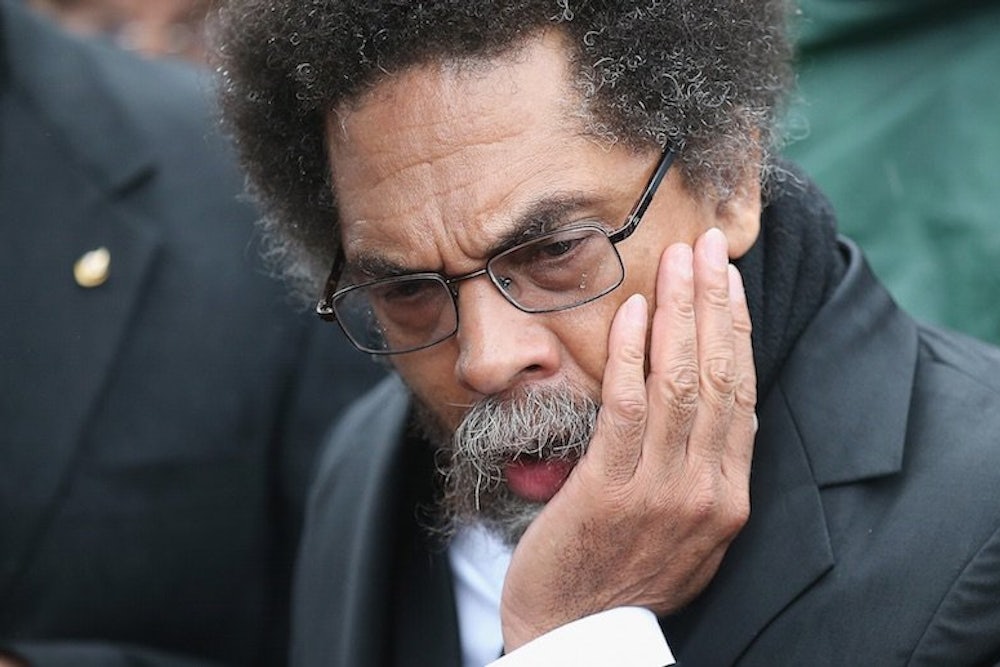

In a justly celebrated and influential book, Cornel West described pragmatism as “the American evasion of philosophy.” West deployed this fine epithet not to condemn but to praise: West was limning the tradition that runs from Ralph Waldo Emerson to William James to W.E.B. Du Bois. These were minds for whom traditional metaphysics was an encumbrance to be cast off, a quagmire of unanswerable questions, a hurdle to the real business of changing the world.

Pragmatism is a noble tradition but there is a type of hyper-pragmatism that has a way of dodging not just philosophy but all forms of thinking. In its most vulgar form, hyper-pragmatism will turn to a figure like Hannah Arendt and ask, “If you are so smart, why aren’t you rich?” But this demand that thinking justify itself in worldly terms is not limited to just those who subscribe to the values of a business civilization. Among the left, there is a hyper-pragmatism that is suspicious of abstract thought, that insists on myopic focus, that extols activism as the highest good, and that deplores any debate among intellectuals as a waste of time while the world grieves. Confronted by any sort of intellectual critique, activist hyper-pragmatism responds by saying “this doesn’t matter, intellectuals criticizing other intellectuals is a trivial indulgence while we face serious problems like racism, economic inequality, and climate change.”

In fact, West himself is guilty of this. After The New Republic published Michael Eric Dyson's “The Ghost of Cornel West,” West, on Facebook, sought to deflect the criticism, writing, “the marvelous new militancy in our Ferguson moment should compel us to focus on what really matters,” and then gave a lengthy (and worthy) list of problems facing the globe.

The problem with this argument is that while problems like racism and climate change are easy to identify, solutions are much harder to come by—and in fact impossible to achieve without intense and serious debate. All serious politics involves developing a program of action. To forego intellectual debate as an unnecessary luxury is to doom activist energy to manifest itself as merely a wail of anguish, a litany of complaints without any agenda.

If we accept the principles of hyper-pragmatism, then it’s never a good time to think and argue, since the world is always full of evils that need to be protested. But in point of fact, the most effective protest movements have been enriched by a realization that debating ideas and strategy matter as much as describing problems. A notable example is African American struggle for liberation, which has been driven forward by a series of contentious debates, ranging from W.E.B. Du Bois’s critique of Booker T. Washington in the beginning of the twentieth century to Harold Cruse’s lambasting of leading figures like James Baldwin in the 1960s. These polemic exchanges were often bitter and personal, but they pushed politics forward.

Back in the '60s, the Marxist cultural critic Theodor Adorno astutely decried what he called the “actionism” of the New Left. “Actionism is regressivism,” Adorno wrote, noting that the advocates of actionism believe “theory is repressive” but in fact “immediate action, which always evokes taking a swing, is incomparably closer to oppression than the thought that catches its best.” The difficult task of building a less repressive world, of walking the tightrope between spontaneity and organization, “cannot be found other than through theory.”

Writing in the Radical Society in 2002, Doug Henwood, Liza Featherstone, and Christian Parenti echoed Adorno’s critique of “actionism,” noting that all too often American protest culture “combines the political illiteracy of hyper-mediated American culture with all the moral zeal of a nineteenth century temperance crusade. In this worldview, all roads lead to more activism and more activists. And the one who acts is righteous.”

Action bereft of thought is sterile. In order to really change the world, we need to be ready to argue about it.