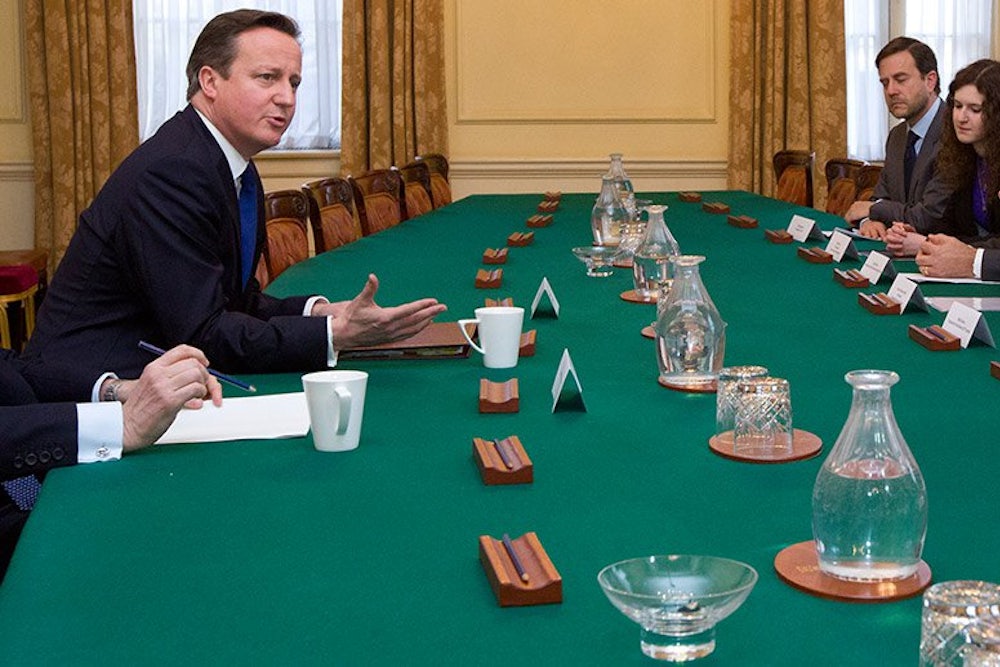

This past Friday, The Atlantic posted part of Jeffrey Goldberg’s interview with Conservative Party leader and current Prime Minister David Cameron. Goldberg introduces the excerpt by observing that Cameron hasn’t just “repeatedly and publicly professed concern about the safety of his country’s Jewish citizens, but” is also “thinking deeply about the nature of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism.” The interview reads, in other words, as pro-Cameron.

In the post, Cameron tells Goldberg, “The Jewish community in Britain makes an incredibly important contribution to our country.” Later he reiterates the “contribution” idea: “So I think in Britain we’re taking the right approach, tackling anti-Semitism, emphasizing the contributions of the Jewish community, and all the rest of it.” In a March speech to a British Jewish organization, Cameron again praised his country’s “Jewish community” for its “contribution,” modified in this case with the word “enormous.”

Given the context—and, perhaps, that his own ancestry includes a Jewish “contributor” or two—it would seem Cameron meant no harm. Cameron offered about as positive a view on British Jewry as one might have expected. But talk of “contributions”—apart from just being patronizing—has a way of reinforcing difference, and, in turn, encouraging xenophobia.

Jonathan Chait expanded on a related point in 2013 in New York magazine, in response to some over-the-top contribution-talk from U.S. Vice President Joe Biden that, Chait argued, delivered “a speech that is likely to be quoted by anti-Semites for years and decades to come.” The flip side of praise is stereotype: Jews are great, until their greatness means that they are controlling the entire world.

More restrained contribution-rhetoric is “standard spiel for praising any ethnic group,” Chait continued. This is true, but it shouldn’t be: Contribution-talk is always a rebuttal to the notion that some segment of society hasn’t pulled its weight, not a way to change the terms of the discussion. Cameron’s choice to respond to British anti-Semitism with contribution rhetoric ends up implying the Jews’ placement in Britain is contingent on sufficient (unspecified) contributions. Does he mean bagels? What they pay in taxes? If Jews were to earn less, or to introduce fewer charming cultural products, would anti-Semitism then be more acceptable?

A more inclusive, yet also unnerving, “contribution” message comes from Green Party leader Natalie Bennett. In an interview with Sandy Rashdy in the Jewish Chronicle Bennet lauded her party for “celebrat[ing] the contribution of migrants to Britain. … I am really proud of the fact that we have stood up against that UKIP rhetoric in a way that the two largest parties have not.” While Bennett deftly avoids Jewish-specific “contribution,” she offers some excessive philo-Semitism of a progressive flavor, conflating “Jewish voters” with “migrants.” If you adore Jews because foreigners are great, you’re on the one hand, rejecting xenophobia, but on the other, insisting upon the foreignness of even native-born Jews. British Jews tend not to be foreign-born: According to a 2007 report based on census data, “The Jewish population of England and Wales in 2001 was mainly indigenous with 83.2 per cent born in the United Kindom [sic].” Moreover, as Paul Vallely’s Independent article, “A short history of Anglo-Jewry: The Jews in Britain, 1656-2006,” reminds, there have been Jews in Britain continuously for centuries.

The trouble with contribution talk isn’t simply that it offends on the micro level. Obviously, anti-immigrant sentiment of the sort that lets hundreds of migrants perish in the Mediterranean is more dire than the fact that Jews are being praised for contributions or equated with migrants. But these things are interrelated. When the best that minorities can hope for is guests-of-honor status, one can't fault them for putting group-specific interests first—in their voting patterns or in other arenas. Persistent assertions of difference, in turn, fuel anti-immigrant sentiment.. Contribution rhetoric also suggests, in a dog-whistle-ish way, that minority groups not deemed sufficiently contributory would not be deemed worthy of defense. If Muslims, Roma, or whichever other group don’t meet right-wing politicians’ “contribution” standards, what then?

Western Europe may seem, from a U.S. perspective, like a secular, progressive sort of a place, to many Americans. But if even British Jews—most of whom are not actually immigrants, and the vast majority of whom are (or at least identify as) white—are treated as permanent pseudo-immigrants, what hope is there for actual immigrants? For actual visible minorities?

Rather than speaking of Jews’ or any other minority group’s “contributions,” politicians should be clear that there is a path toward full belonging. They should promote acceptance of “communities” but also of individuals. Politicians shouldn’t ask that the communally minded chuck out all identity other than national ones, and they should be welcoming of the proudly hyphenated. But they should also remember that not everyone whose name or appearance marks him or her as a minority wants in on organized communal or religious life. Yet everyone who reads as a minority is, by definition, a target of racists and xenophobes. A true rhetoric of inclusiveness would acknowledge existing societal bigotries without reinforcing them.