In 2012, the FDA warned physicians and medical practices that their supplies of bevacizumab, an expensive drug used in combination with chemotherapy to inhibit tumor growth, might be tainted. It turns out some hospitals were literally giving cancer patients cornstarch instead of anticancer meds: The FDA found that some batches of the counterfeit beyacizumab contained no active pharmaceutical ingredients at all.

Tim Mackey, director of the Global Health Policy Institute, said that even today it’s hard to guess exactly how many patients were exposed to the counterfeit bevacizumab; those being treated would have a high mortality rate anyway. “It’s kind of like the perfect crime,” Mackey said.

Further obscuring the extent of the ersatz drug is the maze of grey market distributors it wound through. Before the counterfeit bevacizumab arrived in the United States, investigators found, it traveled through Turkey, Switzerland, Denmark, the U.K., and Canada.

Despite the scope of this scandal, the security of our medical supply chain hasn’t improved much. “It could happen tomorrow and we wouldn’t be any more protected,” Mackey said.

The process for reporting incidents of counterfeited drugs around the world is severely impaired, a study published today in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene has found. Of 169 countries, 127 reported no counterfeit incidents at all, meaning, Mackey said, that many countries are simply ignoring the problem. Without an accurate picture of the security of the medical supply chain, it’s difficult for governments to crack down on drug counterfeiting. The study is the first global-scale assessment of drug counterfeiting.

The study found that counterfeit medicine turned up in a range of settings: from small community pharmacies providing anti-malarial drugs to U.S. clinics providing anticancer treatment. From 2009 to 2011, the study counted 1,799 different types of counterfeited medicine across 1,510 reports of “counterfeit incidents,” which encompass a range of situations or quantities of drugs, worldwide. A customs official unearthing multiple counterfeited drugs, for example, would be counted as one incident.

China reported the largest number of counterfeit incidents, followed by Peru, Uzbekistan, Russia, and Ukraine. However, Mackey said, these finding should be taken with a grain of salt: Countries such as China, which has a reputation for counterfeit medicine, might be looking for counterfeit drugs and therefore turn up more, while other countries, such as India, might be ignoring drug security in part to delay having to address it. “The countries and numbers would look really different,” with more accurate reporting, Mackey said.

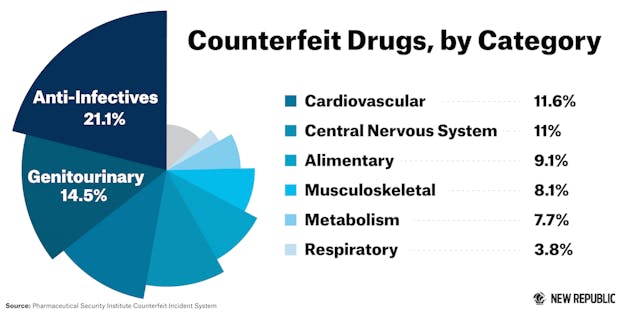

Although the study's data might be limited, it emphasizes the need for a standardized procedure and system for reporting counterfeit medicine worldwide. The majority of counterfeit drugs—about 53 percent—fall under “lifesaving-related drug categories,” the study found.

“There’s this global drug supply chain, and there’s gaps in it,” Mackey said. “We really need to make this a global priority.”