The strange thing about memory is the way in which certain moments can be lost to you for years, even decades, until something or someone reminds you of them, and you feel their sudden presence with a stupid, piercing longing. Stupid because those moments seem too minor, not to mention too long gone, to think back on with any sort of earnest yearning; piercing because despite this, the thirst for them is, as they say, real: Indeed, it feels nearly sexual in the palpable pangs it arouses.

It’s not cool to fall prey to nostalgia—what the writer Svetlana Boym has cited as the “hypochondria of the heart.” It marks you as backward-looking rather than forward-thinking—conservative, sappy, old. Knowing all of this full well, however, doesn’t help much when viewing Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the affecting new documentary about Nirvana’s frontman, directed by Brett Morgen. I couldn’t keep my foot from moving to the music. I couldn’t keep myself from mouthing the words. I couldn’t keep the sobs from rising in my throat.

All of this is embarrassing to admit, but since embarrassment is the central affective mode I remember from being a teenager, it might be appropriate. After all, I was 15 in 1991, when Nirvana released their major-label debut, Nevermind, its combination of sonic ferocity and wistful sweetness blowing my mind and cracking my heart. In his music and lyrics, Cobain traced a utopian arc—suggesting that a world of authentic, unencumbered energy and feeling could be possible—while simultaneously signaling that such a world could only be sensed briefly, not fully accessed. Something—disappointment, oppression, corporatism, self-hatred—was always in the way. In this, Nirvana felt nostalgic even on first listen. Remember when we glimpsed that moment, how good it was, but how fleeting?

I’m 39 now, and Kurt Cobain’s story still feels significant, not just to solipsistically remind myself of how I felt as a teenager, but also to mine what American popular culture has tended to uphold as valuable, then as well as now. It’s been more than two decades since Cobain committed suicide with a gunshot to the head in 1994, enough time to look back and observe the meaning not just of that gesture, but of his life—one whose highs and lows were carried out in a striking but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to circumvent the conventional tenets of the American dream.

Montage of Heck begins with footage of Cobain as a golden blond child, beloved firstborn of his young parents. The small logging town of Aberdeen, Washington, where the family lived, was an American Eden, his mother Wendy O’Connor claimed in an interview. “Everybody had everything. Even if you didn’t have a lot you still had enough.” Sweet early drawings of Cobain’s, featuring happy cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and Snoopy, reflect this sense of safe, prelapsarian plentitude, as do home movies of the jokey Cobains, still a couple during their son’s early years. When she got married, O’Connor said, she felt: “All those problems are behind me. Now I’m just going to have babies.” After she had Kurt and his younger sister Kim, though, she “started to mature,” and began to ask herself: “Is that all there is?”

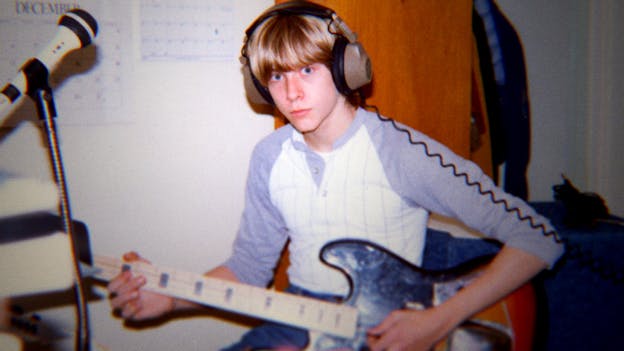

The film suggests that O’Connor’s of-its-time awakening led to the Cobains mid-’70s divorce, which, along with young Kurt’s hyperactivity and propensity for trouble, seems to have contributed to an accelerated transition from a relatively protected, chubby-cheeked childhood to a delinquent, bony-limbed adolescence. The tonal shift of the archival footage from the bright colors of the 1960s to the grainy dinginess of the following decade mirrors, too, the country’s collective move from hopeful prosperity to depression and apathy, affective states Cobain was increasingly burrowing into. Alcohol and drugs helped: “I discovered the most ultimate form of expression ever: marijuana,” he is heard saying in an audiotape. “I could escape all day long.”

For the burgeoning musician, escape seemed to translate into being the worst kid possible as well as the most creative, figured as two sides of the same coin. The documentary conveys this doubled sense of always-impending disaster and relentless, almost autistic artistic efflorescence through remarkable animated segments, in which Cobain’s journal writings as well as his grotesque, Zap Comix-style drawings—no more benignly grinning Disney characters—are jitteringly brought to life, and his taped words are married to realistically rendered narrative cartoons. In the most depressing of the latter, Cobain’s voice-over recounts a disturbing tale in which he and his high school friends stole alcohol from a mentally challenged girl. Cobain later returned and—eager to rid himself of his burdensome virginity—came close to having sex with her. (In the film, Cobain recounts asking the girl if she’d had sex before; she casually affirmed that she had, “mainly with her cousin.”) It’s to the film’s credit that it doesn’t attempt to soften Cobain’s involvement in this burnout hell. It’s a nightmare very much dressed like a nightmare, and Cobain’s turning this world’s dregs into art is figured as a more compulsive, inexorable reaction than act of redemption.

Redemption, in fact, is hard to come by in Montage of Heck’s retelling of Cobain’s life. And in this, it seems to remain true to Cobain himself, who, over and against his driving ambition to succeed—the film pegs this, in part, to the rejected child’s desire to be loved—was famously never really able to enjoy the spoils of his critical and material success. In an early journal entry, he wrote: “Tomorrow morning I would like every one of you to buy a firearm and assasinate [sic] a representative of gluttony.” Once Nirvana had made it, this almost anti-American attitude continued to inform Cobain’s understanding. A chronic stomach condition was his constant companion, and suffering, rather than triumph, marked his notion of creativity. The only type of excess that interested him was luxuriating within the soft embrace of numbing opiates. In the words of Cobain’s former wife and rock-star-in-her-own-right Courtney Love (who cooperated with Morgen on this film, providing him with access to many never-before-revealed archival materials), “Kurt said, ‘I’m gonna get to three million dollars and then I’m gonna be a junkie.’”

There seems to have been real intention behind this Robinson-Crusoe-on-smack fantasy, with Cobain envisioning himself self-sufficiently retiring to his metaphorical island with just enough drugs to not ever have to engage with the rest of the world again, save perhaps for Love. In one archival segment, the couple is seen comically playacting the part of desperate junkies for the camera, coughing and shaking while sitting on a mattress laid on the floor: “If we weren’t so needle-sick,” Cobain said, “I could be on tour with Guns N’ Roses now, whooping it up, snake-dancing across the stage.” Cobain’s positioning of himself against Axl Rose is telling. While Guns N’ Roses’ troubles with heroin were as well-documented as Cobain’s, that band, in opposition to Nirvana, was clearly marked by its Gatsbyesque embrace of success’s booty, becoming, by the early ’90s, a gargantuan, bloated machine putting out double albums, touring with a full orchestra, and releasing lengthy ballads accompanied by hyperproduced, scripted videos.

The irony, of course, is that Nirvana itself became grotesquely successful. The moment in which grunge achieved mainstream prominence is shown in Montage of Heck to be monstrous and terrifying, with surging crowds teeming with bare-torsoed, baseball-cap-wearing white teenage boys (not that different, in fact, at least outwardly, from the white teenage boy Cobain once was). When asked in an interview about his feelings vis-à-vis Nirvana’s ascendance, a morose Cobain, wearing a dress and sunglasses, muttered, “Everybody wants to be hip. Everybody wants to be accepted.” The fact that Cobain, as the film shows, was so talented, so gorgeous, so funny, so vibrant, especially when onstage (“God I love playing live,” he wrote in his journal), was probably to his detriment.

This resistant attitude seems, from today’s perspective, both condescending and quaint—much like Cobain’s wearing of his “Corporate Magazines Still Suck” T-shirt on the cover of Rolling Stone—but I have to admit I sort of miss it. There’s a lot to be said for hating capitalism and the Man, and I certainly do, though I wouldn’t go as far as pretending that I’m not part of the problem. While watching Montage of Heck, I noticed suddenly that I had on a $135 Theory version of the ratty gray sweatshirt Cobain is seen wearing in archival footage of a Nirvana soundcheck. Granted, I got it on sale, but the point still stands. Dissent, partly commodified in Cobain’s time, has since been completely subsumed into the lubricated interactions of the marketplace.

The true prescient figure in the Nirvana orbit was, really, the fascinating Love. Her profile over the 20 years that have passed since Cobain’s suicide can be taken as an instructive template for the way things would have gone had Cobain not chosen to take his life. Preternaturally smooth-faced, her blond hair long and flowing, Love speaks candidly in the movie about her loving relationship with Cobain as well as their heroin use—most controversially, during her pregnancy with their daughter Frances Bean—and generally comes across as a very intelligent drama queen who has seen a lot, with a soupçon of well-preserved Beverly Hills Real Housewife. What is made clear is that despite the way the narrative has been told and retold—with Love cast as the smacked-out Jezebel who led to her husband’s demise—Cobain was clearly on a death trip from a very early age, and would have probably reached his end even without the allegedly bad-news Love by his side.

In fact, even as an acne-dappled, rat’s-nest-haired relative nobody, Love, contra Cobain, always seemed like a survivor, particularly in her unquenchable thirst for life and its rewards. She was sexy and smart and loud, and she didn’t have any qualms whatsoever about wanting to be the girl with the most cake. One early letter she wrote to Cobain, and that is featured in the film, reads: “Kim [Gordon] says we are the hottest rock couple since Sean and Madonna.” In an infamous 1992 Vanity Fair interview, in which Lynn Hirschberg quoted sources suggesting Love was shooting up while pregnant, Love spoke of her time as a stripper, evincing a clear-eyed long view if there ever was one: “I see girls now who are trying to be alternative. They won’t make a dime. You’ve got to have white pumps, pink bikini, fucking hairpiece, pink lipstick. Gold and tan and white,” she said, only to finish with this devastating, cautionary kicker: “If you even try to slip a little of yourself in there, you won’t make any money.”