Scott Craft knew right away that something was wrong. In all his time at Cargill Meat Solutions, a beef-processing plant just north of Plainview, Texas, he had never seen so many security guards as were on duty that day in January 2013. During Craft’s six years at the plant, he had been promoted from the kill floor to the butchering line (known as “fabrication” or just “fab”) to a warehouse manager, so he happened to be outside on the loading dock when the line of cars pulled through security.

The plant sat on a lonely stretch of Interstate 27, roughly halfway between Amarillo and Lubbock. It was bordered to the west by the highway and the freight railway but was otherwise isolated—well outside the Plainview city limits, surrounded by expanses of cotton fields, and accessible only by a lone farm-to-market road, unused except for the steady flow of cattle trailers in and out of the loading area. By nine-thirty that morning, as the line of cars parked in the employee lot, the sun was high and so bright that the concrete plant seemed to glow white under the glare. Men with briefcases, flanked by additional security guards, exited the cars and disappeared through the main entrance.

Minutes later, supervisors swept through the plant and out to the loading docks. “Everybody go to the cafeteria!” they shouted. As Craft shuffled into line for the lunchroom, he noticed that the chain conveyors that carry beef carcasses along the cutline had been halted. On a typical day, the plant processed 4,500 cattle, more than 1.1 million head per year—nearly 4 percent of all cattle slaughtered in the United States. To meet that kind of demand, Cargill ran two shifts and never halted production during work hours. “When you see fab and the kill floor break at the same time,” Craft told me later, “there’s something going on.” Once the cafeteria was filled with hundreds of employees and hundreds more spilling out into the hallways, one of the briefcase men, John Keating, president of Cargill Beef, stepped up onto a lunch table. He switched on a loudspeaker and started delivering from a script.

The plant was to be shut down. They were told that those who wished to be considered for entry-level positions at the Friona plant, some 75 miles away, or wanted to apply for jobs in Kansas and Nebraska, where Cargill would shift its operations, would be allowed to do so. Those who did not want to move would be issued severance payments, according to seniority, and would qualify for career retraining. For now, they should all get their things and leave.

Craft estimated that half the gathered employees didn’t speak enough English to understand what was being said. Still others were too far away to hear. A ripple moved through the crowd as everyone tried to figure out what was happening. Finally, Craft yelled out, “Hey, the plant’s closing, man. That’s what they’re saying. Everybody go home!” Keating stepped down from the lunch table and was whisked away by security.

Craft said he heard later that higher-ups at Cargill were worried that the employees would be angry at the news. To forestall any organized response, the company didn’t inform any of the supervisors until an hour before everyone was called together. The extra security was meant to stave off vandalism or even the possibility of violence. But there was none of that. Some people cried as they left, wondering what would happen to them—and what would happen to Plainview. Craft watched as the men with the briefcases got back in their cars and left.

In a single morning, Cargill, the largest privately held company in the United States—one spot ahead of Koch Industries—with annual profits of approximately $2 billion, had put 2,400 people, roughly one out of every six adults in the city of Plainview, out of work without so much as an explanation. In the short term, federal assistance secured by the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 540 helped former Cargill workers get extended unemployment and job retraining—and pumped millions of dollars into the local economy, keeping Plainview temporarily afloat. But soon, the citizens of Plainview began to worry that the idling of the plant signaled a more serious concern on the horizon.

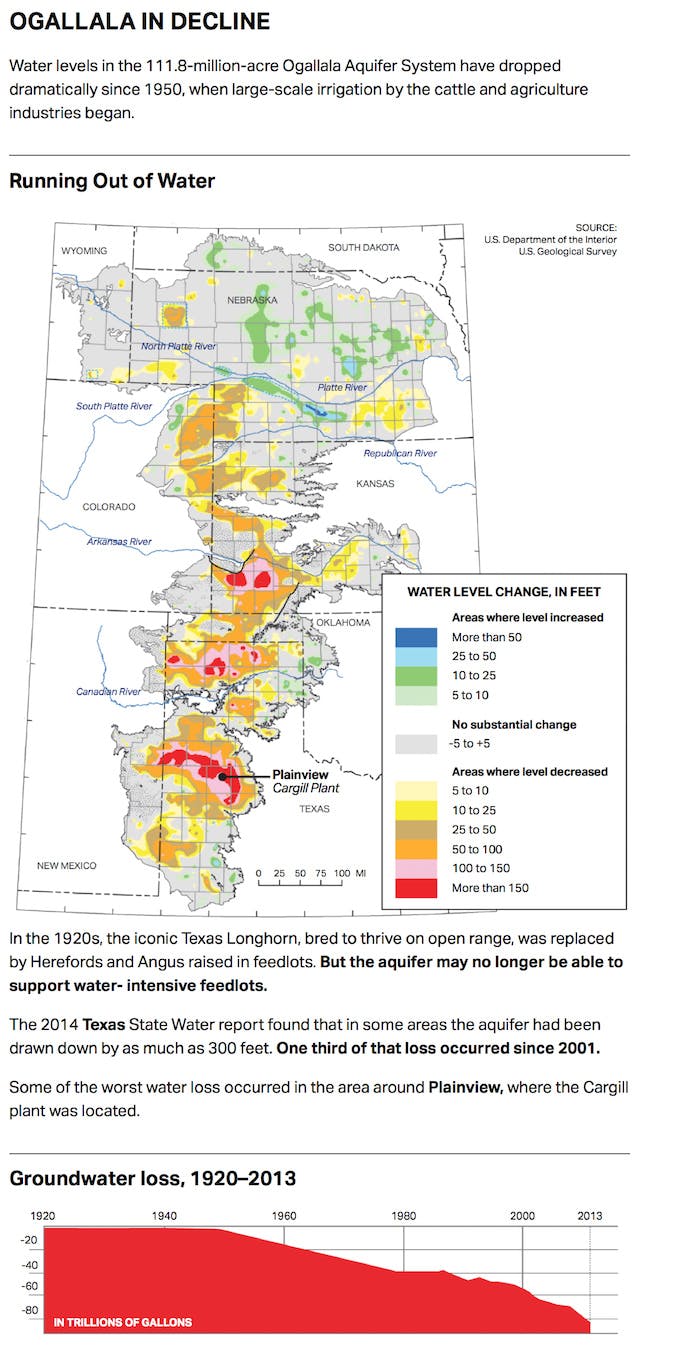

As measured by the U.S. Drought Monitor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, almost the entire South Plains region of Texas was in “extreme drought” or “exceptional drought,” the two worst classifications, indicating widespread crop losses and water emergencies. And the drought has continued ever since. Surface ponds and streams have dried up, which has, in turn, forced farmers and ranchers to rely on groundwater, particularly the Ogallala Aquifer system, to meet their needs for row crops and watering livestock. But those resources, too, have dwindled, compelling many ranchers to reduce their herds. Nationally, by 2013, the total herd of beef cattle in the United States had fallen to its lowest point since the Great Cattle Bust of the 1950s—but the hidden crisis within that fact was that 13 percent of the decline was in Texas, the largest drop in herd strength nationwide. The drop was so severe that, by February 2014, Nebraska had replaced Texas as the nation’s top cattle feeder, an iconic shift that signaled the true scale of the environmental disaster that had befallen the state.

Soon, environmental activists and reporters began to ask whether “drought”—a temporary weather pattern—was really the right term for what was happening in the state, or whether “desertification” was more appropriate. “We’re on our fourth year of drought,” Katharine Hayhoe, director of the climate science center at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, told the industry magazine Meatingplace. “In order to replenish depleted reservoirs and soil moisture, we don’t need just a normal year or just a single rainfall. We need an unusually wet year to get back to normal conditions.” But the early months of 2015 have seen less than 1.4 inches of total precipitation—not even a third of what is considered normal rainfall, much less enough to replenish surface water and groundwater resources.

In fact, hydrologists estimate that even with improved rainfall, it could take thousands of years to replenish the groundwater already drawn from the South Plains. If sustained rains don’t come soon, the tiny cattle towns of the Panhandle and across North Texas, already in decline for decades, may be pushed out of existence. Their residents, like the workers displaced by the Cargill plant closure, may be forced north in the first wave of U.S. climate change migrants, as the national cattle herd constricts around a narrower band in the center of the country and the nation’s food supply becomes ever more reliant on the deepest parts of the Ogallala Aquifer in Kansas and Nebraska. Worse still, for Cargill, as the public begins to worry that the drought in Texas, and the equally alarming drying out of Central California, might be the status quo instead of a seasonal calamity, they are also beginning to question whether the beef industry might not only be victim to the ravages of climate change but also significantly to blame.

In 2011, Fortune magazine called Cargill “The Quiet Giant That Rules The Food Business.” But if the company is a giant of food, it is the central deity of ground beef. No matter where in this country you get your hamburgers—from the drive-thru at your local McDonald’s; at any sit-down chain restaurant from Red Robin to Ruby Tuesday’s; or even if you made them yourself from ground beef purchased at the discount section at Walmart or its grass-fed analogue at Wegman’s—there’s a good chance they passed through a Cargill packinghouse. Roughly one out of every four cattle slaughtered in the United States each day is processed in a Cargill plant. In all, that’s about 20 million pounds of meat daily. But Cargill is a beef behemoth in crisis.

The company has not only shuttered the slaughterhouse in Plainview, but also one of its largest feed operations, in nearby Lockney, where it once fattened 120,000 head of cattle per year. Cargill also closed a corn-processing plant in Memphis, another beef-packing plant in Milwaukee, and a meat-slicing facility in Springfield, Missouri—all due to the contraction of the industry around the reliable water resources in the middle of the country. Last year, Greg Page, the executive chairman of Cargill’s board, acknowledged that rising temperatures and falling water tables were a growing trend. He warned that if nothing is done to stop climate change, crop yields will continue to fall, mortality rates among livestock will rise, and natural disasters will play havoc with Cargill’s supply routes.

In October 2013, Page joined the Risky Business Project—a coalition task force co-founded by progressive billionaires Tom Steyer, Michael Bloomberg, and Hank Paulson (only worth $700 million) with the stated mission of educating members of Congress on the negative effects of climate change on the U.S. economy. The project, Page said, would build on Cargill’s existing partnerships with the Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund. It would also draw on the millions of dollars the company is giving to the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change and at Stanford University’s Center on Food Security and the Environment.

Activists, not surprisingly, have questioned the sincerity of these initiatives. In 2006, Greenpeace released a report, “Eating Up the Amazon,” which exposed Cargill’s role in destroying rainforests to grow soybeans for cattle feed—despite the company’s public partnership in Brazil with the Nature Conservancy. In 2012, a Stanford study claiming to disprove the health benefits of organic food was widely questioned after critics claimed that Cargill had influenced the outcome. (Stanford said Cargill’s donations were directed to a different research center within the same institute.) So observers were understandably cautious about praising Cargill’s ventures into funding climate change research, especially given Page’s reluctance to openly acknowledge the consensus around existing climate science.

“We don’t need to agree—is this man-made, long-term climate change?” Page said in a Cargill-produced video on the company website. “What we do need to agree is, in the past 40 years we have seen phenomena in our area, in our experience, that cause us to say: If we need to change, can we? If we need to change, how are we going to go about that? If we need to change, who are the other people in the supply chain that we rely on, in order to make that happen? Each of these conversations can be held without having to first agree on what is the exact science of the phenomena that we are encountering.” Page is less an evangelist for climate science than a pusher of a capitalist equivalent to Pascal’s Wager: Given the possibility that climate change may exist, a rational businessman should act as if it does, whether he believes it or not.

But Cargill’s eagerness to sidestep the “exact science” also allows the company to conveniently ignore the mounting evidence that points to the beef industry as a prime driver of climate change. A 2013 study by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization found that greenhouse gas emissions from the cattle industry now exceed the emissions released by all the cars on America’s roadways. Feedlot cattle—much of it owned by U.S. corporations—may generate as much as 10 percent of all human-caused emissions contributing to climate change globally. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization now also lists industrial agriculture as a greater risk to global climate change than the clear-cutting of old growth forests. Domestically, by acknowledging the global impact of the effects of climate change, Cargill would, at the very least, seem to run the risk of stiffer governmental regulation. But the company appears to have a plan for that. In the midterm elections—after the creation of the Risky Business Project—the main recipients of Cargill’s campaign donations were House Speaker John Boehner, who has vocally advocated for stripping the Environmental Protection Agency of its power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions; Representative Erik Paulsen who, when asked if he believes humans are contributing to global warming, responded, “I’m not smart enough to know”; Representative Kevin Cramer who denied that humans are contributing to climate change and said that calls for reduced greenhouse gas emission are “all based on this fraudulent science from the EPA”; and Senator Bill Cassidy who suggested that climate change might be caused by “a shift in the axis” of the Earth. Cargill also vigorously supported Mike McFadden in his failed bid to unseat Democratic Senator Al Franken; during the campaign, McFadden declared concerns about climate change to be not “based on science” but “based on emotions.”

Is Cargill hoping to awaken politicians to the realities of climate change, in order to prevent further closures like those in Plainview? Or is it looking to head off potential regulation that would impose limits on resources, most notably water, in the places it is headed next? In April, I asked Cargill Beef for interviews with Page and Keating, in order to pose these questions. Michael Martin, head of Cargill’s external communications office, wrote to say, “We will not set up in-person or phone interviews.”

Lindan Morris is a towering man with a gentle smile. In March, outside his store, he plucked his sunglasses off and shook my hand firmly. His business, Floyd County Farm & Ranch Supply, stands at the entrance to downtown Lockney, which is east of Plainview, and just across the street from a cotton gin, whose dryer fan roared and sent cottonseeds swirling as if we were trapped in a snowstorm. Inside the office, a commemorative Roger Staubach Dr. Pepper bottle decorated a shelf; the walls were covered with John Wayne posters and an oak plaque mounted with a photo of Nolan Ryan’s famous headlock on Robin Ventura. Atop Morris’s bank of file cabinets was a miniature Zimmatic center pivot—a gift from one of his sons, who works for Lindsay, manufacturer of the irrigation systems, in Amarillo. Morris himself is the local dealer and installer of the giant, rotating sprinkler systems, which automatically pump from single underground wells and disperse water evenly over as much as 640 acres. I asked how sales were doing in the area. “Way down,” he said.

I met Morris for the first time last fall, when he came into the Tastee Burgers on Main Street and mentioned to some local farmers that he had been digging a pivot well nearby. “We dug down to a depth of 292 feet in one place. No water,” he said. “The next went to 360 feet before we hit water.” When I reminded him of that day, he nodded. “Happens from time to time,” he said. “Most of the time you can find some water. You just don’t find very much.”

All of the usable groundwater in the area, for cattle and drinking, comes from the Ogallala Aquifer, an underground, freshwater reservoir that accumulated from millions of years of High Plains rain and snow seeping down to the underlying “red bed”—a layer of impermeable rock, some 300 to 400 feet below the surface. Morris said the red bed has peaks and valleys; if you hit a low spot, you can still find water in it, but if you hit a high point, you can’t.

This was not always so. In the late nineteenth century, when Christopher Columbus Slaughter, a rancher from east of Nacogdoches along the Louisiana line (who claimed to be the first male child born to parents married in the Republic of Texas), moved his herd here and settled atop the Llano Estacado—the thick top layer of limestone that defines the eastern edge of the aquifer—the underlying reservoir was so full that there was an abundance of sub-surface water sources. Slaughter’s Lazy S Ranch grew to encompass everything from what became Plainview all the way to Big Spring—a distance of more than 150 miles, earning him the state-appropriate nickname of the Cattle King of Texas. Slaughter was ambitious, and decided to purchase for his herd gold medal Hereford bulls from international competitions, often paying thousands of dollars a head, in order to establish the finest line of beef cattle. He crossbred Kentucky blooded shorthorn cattle with local longhorns from Spanish stock to create the iconic Texas Longhorn, a breed specifically designed to be able to survive on the scrubland of the open range. At the turn of the twentieth century, Slaughter began digging wells for his growing herd of 20,000 breed stock. For most of his wells he needed only to deepen a natural arroyo or a buffalo wallow, using a horse-drawn trench digger. In other places, Slaughter hired men to drill wells and install windmills to pump water into stock tanks spaced five miles apart.

“Some of the first wells here were hand-dug,” Morris said. “So that tells you how shallow it was to water. Then in the 1950s, they were still finding some water at fifty feet down.” Morris grew wistful. “Today you have to dig all the way to red bed.”

By the onset of the latest drought, the groundwater shortage had grown so severe that the State of Texas commissioned an in-depth study to quantify the problem. The results, published in the Texas Water Report in January 2014, could hardly have been more dire. “Since the 1940s,” the study reported, when ranchers, in a surfeit of optimism, began trying to grow cotton on the arid rangeland, “substantial pumping from the Ogallala has drawn the aquifer down more than 300 feet in some areas.” But the real trouble has been recent. One hundred feet of the 300-foot decline of the aquifer occurred in the decade between 2001 and 2011. This period coincided with a run-up in commodity prices that tempted farmers to start growing thirsty feed crops. With rising temperatures and what the report described as “the near-total absence of rain” of the current drought, water use for irrigation has jumped another 43 percent.

Worst of all, the portion of the Ogallala Aquifer south of the Canadian River in the Texas Panhandle, where Lockney and Plainview sit, is cut off from the main aquifer system. As a result, the reservoir recharges more slowly than the northern portions that supply irrigation water for most of the Central Plains. So as Texas Panhandle farmers chased commodity profits and tried to keep pace with corn production in Nebraska and Iowa, they pumped out the aquifer faster and faster, draining the great basin of water that had sustained Texas cattle for two centuries.

All of which helps explain why wells at the edge of the Ogallala basin are starting to come up dry. To show me, Morris pointed to a satellite map of the area on his office wall. “Most of Floyd County is cut up in one-section blocks,” he said. The dirt roads, spaced at even mile markers, describe a perfect grid over the landscape. Around Lockney and stretching west back toward Plainview, each section contained a green circle, where a center pivot was irrigating a field of corn, soybeans, or cotton. But east of Lockney, the circles were smaller—pivots covering just one or two quarters of the section—or the larger circles were only covering part of the square, like a half-eaten pie. Still farther east, moving toward the edge of the caprock, there were no green circles at all. “This was all, at one time, irrigated farmland—all of it,” Morris said with a sweep of his hand. But the wells there have run dry. And the farmers have all picked up and left—which means ranchers are left without water and feedlots are left without food.

Despite everything, Morris couldn’t accept the idea that he might be witnessing the effects of climate change. “I don’t see the science behind the global warming thing,” he said. “There’s always been times when it was hot and dry, and there’ll be some more.” But when I pressed him in Cargill’s querulous style—what if climate change is real, what if the hot, dry times were permanent—he stiffened. “If climate change is the real deal,” he said, “then the human race as we know it is over. And I don’t believe that.”

Morris, like so many in Texas, has perfect faith in our ability to innovate and overcome whatever immediate challenges we may face. Still, he had to concede that he had seen the line of dry wells advancing on Lockney in his lifetime—and without water, there would be no way to raise feed, much less cattle. “If the drought continues, it’ll get to where it’s not economically viable to farm here, and there won’t be any farmers. The land will eventually go back to grass. And five hundred years from now, maybe somebody will have enough rain over enough time to replenish the aquifer.” Morris smiled. “And they’ll start farming again.”

Tall and lanky with cowboy boots and a long Texas drawl, Mayor Wendell Dunlap was frank about the water level in Plainview. “It’s dropping,” he said. “Definitely.” Still, he emphasized that the city was faring far better than some surrounding communities. “There’s an area, especially east of Lockney, that’s really turned into a dryland area,” he said. “There are pockets of water. There are places that have pretty good water, but then you go a mile or two, and they’re struggling to find water.” Like Morris, Dunlap saw no global factors at play in the aridity: He attributed the water shortage to no more than over-irrigation. The area had seen a boom in dairy cattle in recent years, he said—milking barns with as many as 5,000 cows actively in production and perhaps twice as many on the surrounding lots. All those cattle require a lot of water, but they also require year-round feeding. While most local farmers will plant a single crop each year, he explained, corporate-controlled land around feeding operations was typically “double-cropped”—and thus uses twice the water resources. “There was a movement by the water conservation district to set limits,” he said, “but that hasn’t met with a lot of support.” He chuckled at the thought. “Farmers in this area,” he said, “don’t particularly want someone to tell them what they’re supposed to do.”

Many still cling to the water-intensive methods that made Plainview a hub of the cattle and cotton industries in the 1920s. Farmers back then raised short-fiber cotton with such remarkable success, thanks to plentiful groundwater, and the lack of boll weevils, that by 1935, the West Texas Cotton Oil Company had built mills in Plainview and neighboring Lockney. Those cotton farmers with cattle holdings established large-scale feeding operations adjacent to their cottonseed oil mills. They would feed the cattle on meal and hull byproduct and turn former ranchland into more acres of cotton. With the abundance of food, the hardy but Texas Longhorn was steadily replaced by shorthorn breeds like the Hereford and Angus, as well as new specialty breeds like the Beefmaster.

And the economy of West Texas, especially Plainview, boomed. The downtown saw the construction of the Granada and Fair vaudeville halls. The city erected the 3,000-seat Plainview Municipal Auditorium. In 1929, Hilton built a seven-story hotel with 125 rooms, all with private baths. The cotton and cattle industry also brought windmills and irrigation to the surrounding fields, encouraging the planting of wheat and feed crops. B.F. Yearwood, a local entrepreneur, erected a 50,000-bushel corn mill at the edge of town. The Harvest Queen flour mill, which opened its doors in 1907, was completely rebuilt with soaring concrete grain elevators. The city was so convinced of its limitless water that it planted more than 50,000 shade trees as part of a beautification project. In 1937, at the height of the Dust Bowl, the McCormick company issued a postcard, intended to attract drought-stricken farmers from Oklahoma to Plainview. A young farm girl is shown holding the lead of a beef cow and standing next to an open irrigation well, its windmill spilling water into a verdant-ringed stock pond. The legend reads: “This modern farmerette has no rainfall worries.”

Today, the iconic art deco buildings along downtown Plainview’s broad, brickwork avenues are sun-scorched and shuttered. The plywood bolted over the front windows of the Hilton is painted with a mural of the former lobby, but the locals now speak only of ghosts lurking in the abandoned upper rooms. As the community limped through the droughts of the ’50s and ’70s, and the earth-parching heat wave of the early ’80s, the cotton industry struggled to stay profitable, and gradually the area returned more and more to cattle feeding and beef processing. With the arrival of the Great Recession and the onset of the current historic drought, Plainview seemed to lose what was left of its other industries: the White Energy ethanol plant closed temporarily, the Peanut Corporation of America plant shuttered due to a salmonella outbreak, and the Harvest Queen Mill & Elevator (by then owned by Archer Daniels Midland), also closed—collectively taking with them more than 1,000 jobs in a town of just 22,000 people.

The Cargill plant closure meant not only the loss of another 2,000 jobs for official company employees, but also its horizontal brethren: hundreds of additional workers at Packers Sanitation Services, which cleaned the plant; Marshfield Foods, which provided inspection services; and Cargill Cattle Feeders, which raised cattle in Lockney. The departure of Cargill also had a swift and devastating ripple effect in the broader community: convenience stores and restaurants went out of business, real-estate offices and furniture stores reduced hours, car dealerships went under, as did two elementary schools. Within a year of Cargill idling the plant, Plainview and surrounding Hale County, a network of communities comprising fewer than 12,000 households, lost nearly 4,000 jobs.

Mayor Dunlap was determined to beat the odds—and show-up the naysayers who predicted that Plainview would dry up and blow away. He brought in millions in federal and state assistance for job retraining, and the city offered grants and loans to anyone looking to start a business, especially anyone willing to set up shop in the half-empty downtown. Scott Craft and his wife Nancy decided to turn his layoff from Cargill into an opportunity. With seed money from the city, they put their savings, and Scott’s severance, toward opening a hair salon on East Sixth Street. The storefront, across the street from the courthouse on the main square, has been home to a string of unsuccessful businesses—a cigar shop, a children’s used clothing store, an auto-body detailing shop—but Craft thought he and his wife could make it work.

When I visited, Craft had transformed the space into a salon worthy of Dallas, but it remains an open question whether a dwindling community can support businesses of this sort. Craft is set on staying—he has a tattoo of the state of Texas that engulfs his entire right forearm—but there’s no denying that Cargill chose to close the Plainview plant and the Lockney feedyard because the dry edge of the underground basin of the Ogallala Aquifer is encroaching. For now, the company takes advantage of two daily shuttles, purchased by the Texas Department of Transportation and operated by a local nonprofit, to carry employees from Plainview on the 150-mile round-trip to the Friona plant. Cargill increased production there and added jobs after the Plainview closure. When I spoke to employees waiting for the bus, they complained bitterly about eight-hour shifts stretching into ten hours to keep up with production, plus four hours spent on the bus. Not only are employees unpaid for that commute time; they have to chip in $45 per week to Cargill to cover the driver.

One worker told me he was only enduring the long days in hopes that Cargill would one day reopen the Plainview plant. “Maybe if this drought ends,” he said. For now, while the chair of Cargill’s board claims to be fighting climate change, the president of Cargill Beef blames the Plainview closure not on drought or desertification, but on a “media frenzy” against lean finely textured beef (popularly known as “pink slime”) and legislation requiring country-of-origin labeling. He blames the reduced poundage of beef on Merck’s 2013 decision to suspend production of the muscle-building feed additive Zilmax, because animal welfare advocates showed that it caused the hooves of cattle in dry climates to split or even fall off completely.

I asked the workers what they would do if the plant never reopened—but before they could answer, a Cargill security guard appeared, red-faced and sputtering, to order me away. Later, a Hale County sheriff’s deputy issued me a warning against criminal trespass, sworn out by Cargill’s contract security team, though the deputy conceded I hadn’t trespassed on company property.

On the narrow platform of their drill rig, Ken Grant and one of his workers from Hi-Plains Drilling sent up varicolored plumes of dust and sand as the rotary bit moved deeper in the ground. Each length of pipe buzzed through the substrata, and then Grant would hoist another on the mast, attach it, and keep drilling. He wore a full brim hardhat and UV shades against the unrelenting sun. His salt-and-pepper Hulk Hogan-meets-biker mustache was caked with red dirt. Grant was sinking a test well to determine if the Ogallala Aquifer was completely dry in this area east of Lockney. When dug, the actual well, which was located just on the other side of Grant’s truck-mounted rig, would go all the way to the Santa Rosa Formation, a part of the brackish Dockum Aquifer system that underlies the Ogallala by another 400 feet. “It’s eight hundred fifty feet to water here,” Grant said. Regulation requires pouring a concrete case around the pipe to prevent contaminating the freshwater Ogallala with saline water from the Santa Rosa, but with the Ogallala now completely dry in this region, there was no need.

This particular well was being drilled to service a nearby caliche pit. In the past, the nitrogen-rich lime had been mined for sodium nitrate for fertilizer. But today the natural concrete is being used to lay a staging area for wind turbines arriving by rail at a site east of Plainview, which will then be loaded onto trucks and brought to this site for use on a new wind farm. The wind energy generated here will power the desalinization facility needed to keep the Santa Rosa water from contaminating the surface water. If Mayor Dunlap has his way, it will also provide construction and maintenance jobs for retrained Cargill workers, while supplying a source of energy that won’t further contribute to the intensifying heat of the Texas Plains.

In a nearby field, Lindan Morris was delivering a flatbed of corrugated steel culverts. These would be used to provide roadway access for the trucks that would soon be arriving with sections of towers and blades for the wind farm. Morris watched the cloud of dust from the drilling rig sweep across the neighboring fields. Dry wells like these were the reason Cargill had pulled out, he said. Cargill Cattle Feeders, the feedlot that supplied the Plainview plant by feeding 60,000 head of beef cattle on a mile-square section, sits less than five miles from where Grant was drilling. “When Cargill owned that, they had purchased water right over land around them,” Morris said, “and there’s wells on the property and wells off-property.” But the open waterhole to the west of the feedlot had dwindled to half its size during the recent drought. Given the dry wells on the literal horizon, it was too risky to rely on the Ogallala Aquifer to make up the difference for water-intensive beef cattle.

In January 2015, Cargill was finally able to sell the vacant feedlot to Western Cattle Feeders. Lockney’s mayor, Tina Graves, who works at the feedlot, touted the sale as a sign of things finally turning around. (“We are just tickled that it’s staying open,” she told the local newspaper.) But Bobby Lofton, the owner of Western Cattle, has stated that he bought the feedlot only after the closure of a National Beef plant in Brawley, California, put his feeding operation in the Imperial Valley out of business. So, he has come to Texas—anything is better than California—but he has filled the stalls not with Angus and other beef cattle developed for Texas feedlots but younger, smaller Holsteins.

“I don’t know if part of those are heifers to go back in the milking barn later,” Morris told me, “or if they’re bull calves that they’re going to grind up into McDonald’s hamburgers.” I told him I had driven by the feedlot, and all I could see were acres of young bulls. He nodded knowingly. In years past, the dairy industry would have killed these cattle at birth, but now their small size—and low feed and water requirement—is regarded as an asset.

After Morris had unloaded the last of his culverts and we had said our goodbyes, I decided to drive east to the place on the map he had shown me earlier. The sun was starting to set and cast a pinkish hue over fence posts and wizened trees along property lines. I drove past the last few ranch cattle, out grazing on green, irrigated grass, and past the fields prepared for the spring planting of corn and soybeans, with no set destination in mind other than a line of wind turbines slowly turning along the eastern edge of the caprock. At some point, I realized I had passed only one other car in more than an hour, and the fields were turning yellow, even in the sunset glow. Barbed wire still separated the road from private property, but all the furrows had disappeared, and the only sign of center pivots were occasional concrete pilings surrounding dry wells, out in the expanding ocean of short-grass prairie. ●