Science fiction often achieves the remarkable feat of being both futuristic and reactionary at the same time. The history of the genre is replete with writers who have given us glittering visions of radically different tomorrows, of robots and androids, aliens and galactic empires. Yet the people who are most closely engaged in the creation of science fiction remain mired in the mundane political realities of the existing world.

Currently, the science fiction world is being torn asunder by a cultural war over diversity, with a hot battle going on over the Hugo Awards, the long-running and prestigious fan-selected awards given out every year at the World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon). Reflecting the demographics of the larger field, the Hugo Awards have traditionally gone to white men, but nominations for women and non-whites have risen in recent years. That trend has upset right-wing fans who say they've been marginalized by affirmative action gone mad—and who organized a successful nomination campaign to undo these gains in diversity, creating an unprecedented party-line slate which has led to the stacking of this year's Hugo ballot largely with white men once again.

“When I heard about this, I was sick at the thought of what they’d done and at all the damage they’d caused,” sci-fi author Connie Willis, who has won eleven Hugos, wrote on her blog. Willis had been asked to be a presenter at this year’s ceremony—Worldcon is scheduled for late August in Spokane, Washington—but has refused, in protest against what she sees as a subversion of the awards. Two writers have been so embarrassed to be on the ballot that they've withdrawn their nominations. And George R.R. Martin, author of Game of Thrones, responded to the fans' demographic anxiety by writing on his blog, “We’re SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY FANS, we love to read about aliens and vampires, and elves. Are we really going to freak about Asians and Native Americans?”

To outside eyes, the struggle over the Hugo can be confusing. It involves the arcane details of a complex nomination procedure, and factions with names like Sad Puppies 3 and Rabid Puppies. But the ruckus makes a lot more sense in the context of science fiction's historical lack of diversity, and there's perhaps no better illustration of that problem than the career of Samuel R. Delany.

In early 1967, Delany, an ascendant star in the science fiction field, sent a manuscript of his novel Nova to Analog, the leading magazine in the genre, to see if they were interested in serializing the work. Although only 25 years old, Delany was already considered a prodigy, having already published eight novels, two of which had won the Nebula Award given by the Science Fiction Writers of America. Delany was also a black man in an overwhelmingly white literary community. Other science fiction writers, notably Robert Heinlein and Mack Reynolds, had tried to imagine a multi-racial future, but Delany brought an unusual level of real world experience to the idea of a diverse tomorrow (and not just because of his skin color: Delany was gay and married to the lesbian poet Marilyn Hacker). Delany’s fiction reflected the complexities of these experiences: The hero of Nova, Lorq Von Ray, has a father of Norwegian descent and a Senegalese mother.

John W. Campbell, the contentious and influential editor of Analog, claimed he enjoyed shaking up his audience with outrageous ideas, but Nova proved too much for him. According to Delany, Campbell called the author’s agent and said that while he liked the novel “he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character.” Campbell’s contention that fans weren’t ready for a book like Nova was belied by the fact that it was shortlisted for a Hugo in 1969.

Campbell used his audience as cover for his own racism. In 1968, he penned an editorial endorsing the segregationist George Wallace for president. Earlier, he had published editorials arguing that slavery was a perfectly sensible system for pre-industrial societies, championing the racial theories of William Shockley and asserting, “One of the major reasons the Negro people are having so much trouble gaining acceptance is, simply, that the Negroes are not doing an adequate job of disciplining their own people, themselves.” Tellingly, among the few occasions that Campbell did allow fiction with black protagonists, it was in a series involving race war in Africa.

In the universe of science fiction, Campbell was no fringe kook: He was the most influential science fiction editor of the last century, whose vision of rule-based, scientifically informed fiction shaped the careers of such canonical writers as Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, and Frank Herbert. For more than three decades, until his death in 1971, he was one of the pillars of American science fiction, a field which indulged his various pseudo-scientific enthusiasms, which included not just racism but Dianetics (he was a pivotal early promoter of L. Ron Hubbard’s claim to be a scientific innovator), a perpetual motion machine, and an ESP-enhancer.

Amid the strife of the 1960s, which polarized science fiction no less than the rest of culture, it was easy to cast Campbell and Delany as diametric opposites: Campbell as the old reactionary apostle of heroic, manly tales of space cowboys, and Delany as the young subversive practitioner of cutting-edge speculative fiction that challenged certitudes about identity. Certainly this polemical divide can be seen in the many polemical battles of the late '60s and early 1970s between partisans of New Wave science fiction and those who loved traditional Campbellian adventure fiction. Yet the contrast between the two men can be overdrawn. In his earliest and best years as an editor, Campbell was an innovator who published work that brought panache and literary technique to the genre and often displayed emotions more complex than the desire for conquest. And while Delany was a stylistic experimenter, he grew up loving such Campbell mainstays as Heinlein and Sturgeon and wrote works that were very much in dialogue with their fiction.

Even Delany himself downplays the divide.

“Today if something like that happened, I would probably give the information to those people who feel it their job to make such things as widely known as possible,” he wrote in 1998 in The New York Review of Science Fiction. “At the time, however, I swallowed it—a mark of both how the times, and I, have changed.”

Ever since science fiction coalesced as a distinctive fan community in the late 1920s (as a result of the efforts of editor Hugo Gernsback), it has been a white boys' club. The virtual absence of non-white writing in the field was paralleled by the near invisibility of women writers. For many decades, the most successful female writers had to cloak their identity with initials, ambiguous names, or pseudonyms (C.L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, James Tiptree, Jr.). Even the women writers who didn’t disguise themselves as men adopted a male point of view in order to get their fiction published. “Writing was something that men set the rules for, and I had never questioned that,” Ursula K. Le Guin noted in a Paris Review interview. “The women who questioned those rules were too revolutionary for me even to know about them. So I fit myself into the man’s world of writing and wrote like a man, presenting only the male point of view. My early books are all set in a man’s world.”

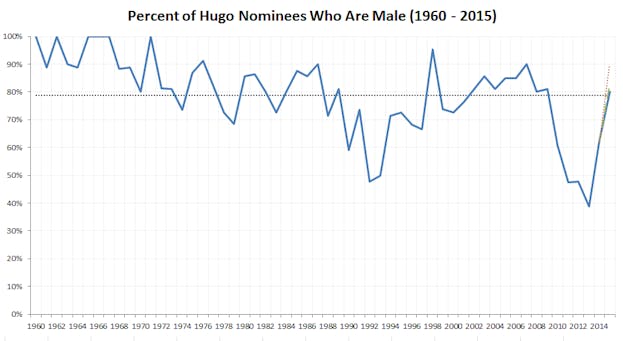

The history of the Hugo Award, created in 1953 and named after Gernsback, is telling. In 1968, Anne McCaffrey became the first woman to win a Hugo for fiction. Between 1959 and 2014, the fiction nominations went to women 22 percent of the time (this statistic is complicated by the fact that one of these female nominees, James Tiptree Jr., was during some of this period widely assumed to be a man). In recent years, the percentage of female fiction nominees has shot up, reaching roughly parity levels between 2011 and 2013.

But the very recent upswing in female fiction nominees is tenuous and now has been reversed because of the backlash from conservative fans. This year, in reversion to historical norms, men make up more than 80 percent of fiction nominees. The Hugo gender backlash is a direct result of a conservative coalition that came together in 2013 under the satirical rubric Sad Puppies.

Anyone who buys a Worldcon membership for $40 can nominate finalists in the 17 categories, which award novels, writers, editors, magazines, graphic stories, movies, and TV shows. The number of people who participate in the nomination process is relatively small—hovering in recent years between one thousand and a little over two thousand—compared with the larger number who vote for the winners at Worldcon. With a thousand votes cast for five nomination slots, an organized slate needs to get only two or three hundred people to all nominate the same people and works in order to force most of their choices onto the ballot. In effect, the nomination process was ripe to be gamed. Earlier attempts to do so were rudimentary. In 1987, the Church of Scientology got a posthumous L. Ron Hubbard novel on the ballot, although in the final vote it finished last (garnering less votes than “No Award"). The innovation of the Sad Puppies has been not to rally behind one single nomination but to create a slate so that they could win the majority of nominations in most categories.

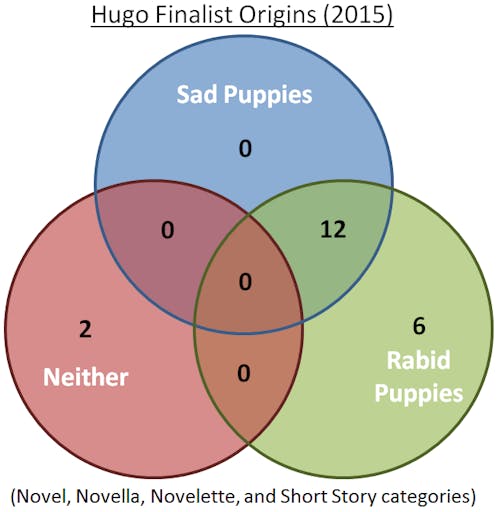

This year, the conservative backlash has been led by two overlapping factions, the supposedly moderate Sad Puppies 3 (the third iteration of the Sad Puppies) and the more right-wing Rabid Puppies. The leaders of the Sad Puppies 3 are Larry Correia and Brad Torgersen, who present themselves as reasonable conservatives redressing an unfair liberal bias. The leader of the Rabid Puppies is the noxious Theodore Beale (who often uses the pseudonym Vox Day). He makes no pretense to moderation. He has written that women should be deprived of the vote and refers to African Americans as “half-savages.” The Sad Puppies 3 and Rabid Puppies constructed overlapping slates for their followers to nominate. This sort of coordinated politicking has never been done before, although it technically does not violate any rules. And it worked: 71 percent of the Hugo ballot consists of nominees promoted by Sad Puppies 3 and/or Rabid Puppies, with the Rabid Puppies list actually doing better. The vile Beale personally has two nominations. One of the books nominated was published by a fringe house, tellingly called Patriarchy Press.

“Basically, what’s happened is that a small group of people... took advantage of the fact that only a small percentage of Hugo voters nominate works to hijack the ballot,” says Willis, the sci-fi author who declined to be a presenter. “They got members of their group to buy supporting memberships and all vote for a slate of people they decided should be on it. Since everybody else just nominates what they like, and those choices vary quite a bit, nobody else stood a chance, and the ballot consists almost entirely of their slate.”

Game of Thrones' Martin, himself a multiple Hugo winner, wrote that those behind slate voting have “broken the Hugo Awards, and I am not sure they can ever be repaired.”

The conservative backlash isn't entirely about attempts to diversify science fiction; it's also motivated by a nostalgia for an imaginary past. The Puppies factions argue that science fiction used to be a fun, apolitical genre but has now become too socially conscious and pretentious, due to a sinister leftist conspiracy.

In a blog post, Sad Puppies' Torgersen argued, “In the last decade we’ve seen Hugo voting skew more and more toward literary (as opposed to entertainment) works. … Likewise, we’ve seen the Hugo voting skew ideological, as Worldcon and fandom alike have tended to use the Hugos as an affirmative action award: giving Hugos because a writer or artist is (insert underrepresented minority or victim group here) or because a given work features (insert underrepresented minority or victim group here) characters.”

Torgersen makes an error which is endemic to the Sad Puppies, conflating literary ambition with leftism and demographic diversity. It is simply untrue that ideology and entertainment are at odds in science fiction. Most major science fiction writers—including the ones who have won Hugo awards from the start—have had strong political convictions which have been reflected in their word. A genre that includes the socialist H.G. Wells, the libertarian Robert Heinlein, the Catholic conservative Gene Wolfe, the anarchist Ursula K. Le Guin, the feminist Margaret Atwood, and the Marxist China Miéville can hardly be thought of as essentially non-political entertainment.

Nor is it the case, despite what the Puppies imagine, that literary ambition is the province only of the left. Much of the best literary science fiction has been written by writers whose politics are right-wing: aside from Gene Wolfe, this includes Jack Vance, R.A. Lafferty, Robert Silverberg, and Dan Simmons. To take one example: Robert Silverberg is a conservative but his best novel, Dying Inside, is a story of a telepath, rich with allusions to Kafka and Saul Bellow—writers Silverberg was emulating. The faux-populism of the Puppy brigade is actually insulting to the right, since it assumes that conservatives can’t be interested in high culture.

If leftism shouldn’t be conflated with literary ambition, neither should it be confused with demographic diversity. Torgersen is assuming that stories by and/or about women and non-whites will automatically be left-wing propaganda. Again, this flies in the face of history. For decades, science fiction writers of both the left and the right, both popular entertainers and those writing more ambitious works, have made a point of trying to be inclusive. Heinlein started featuring non-white characters in his books from the very beginning of his career. His Starship Troopers (1959) can be read as right-wing paean to military virtue; the main character is a Filipino.

Samuel Delany describes himself as a “boring old Marxist” but loves the right-wing fiction of Heinlein. “Well, Marx’s favorite novelist was Balzac—an avowed Royalist,” Delany once explained. “And Heinlein is one of mine.” The largeness of soul and curiosity about differing ideas that Delany brought to his appreciation of Heinlein is sadly missing from all the resentment and angst of the Sad and Rabid Puppies.