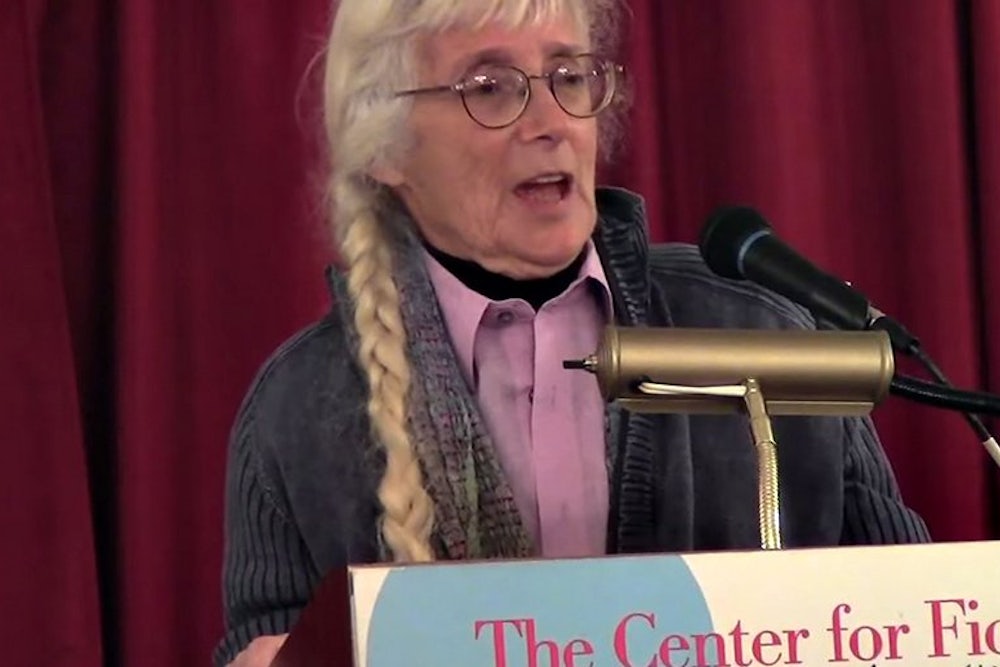

In 2013, during a rare appearance at the Center for Fiction in New York, Renata Adler squinted to address a packed house. Her reading had been studded with self-interruptions—was she too loud? going long?—and the audience had grown vocal, eager for more. The crowd skewed young; literary tote bags dotted the floor. The ghost of Adler’s casual but poignant introduction—“I thought for a while, as I guess people do when they get older, that maybe we are the last generation of readers… and maybe we are all the last generation of writers, too, in the old sense,”—still lingered. “Do you all write?” Adler asked. “It looks as though you all write.”

With the recent publication of After the Tall Timber (New York Review Books, 2015), a collection of Adler’s nonfiction that spans four decades, it’s hard not to recall 2013, the year of her return. That spring, out of the blue, it seemed like everyone I knew was reading and discussing Adler. Copies of her first novel, Speedboat, rested tentlike on coffee tables and nightstands across the city, while snippets of the book circulated on social media. New York City booksellers pushed it as a recovered sacred text.

Context considered, this was an odd and unpredictable hit. Speedboat was originally published in 1976; it had been out of print for decades. Adler herself, deemed a recluse, had been out of the public eye since the turn of the century. She was primarily considered—in the way of a backhanded compliment that manages to evoke either adulation or erasure, depending on the audience—a “writer’s writer,” relegated to college syllabi and used bookstores.

With Speedboat’s republication, Adler earned a new coterie of readers, a twenty-first century version of what was perhaps the book’s original demographic: young people, often employed in creative industries, often living in city apartments, with equal interests in literature, heartbreak, gossip, and the dazzling loneliness inherent to making one’s own way. Speedboat was a cult classic among those who first read it in the 1970s and 1980s. (The recent reprinting was released in conjunction with Pitch Dark (1983), Adler’s second and only other novel.) In the post-9/11 generation—a cohort caught between the promise of an economy that values creative work and the scarring, post-crash economic reality—she has, once again, found a small, devout audience.

As it turns out, readers who started with Speedboat and Pitch Dark came to know Adler backwards. They—we; I— hardly knew her at all.

Adler wasn’t always known as a fiction writer. She was, foremost, a ruthless investigative reporter with an ear for dialogue and an eye for human contradiction. Her writing was morally concerned and lyrical, cutting and fearless.

As a journalist, Adler chronicled firsthand America’s odd beauty; After the Tall Timber reflects that, appropriately roving in its focus. There are articles and essays covering the early Civil Rights movement, Richard Nixon, soap operas, Biafra, the “hippie riots” in Los Angeles, the Six-Day War, and Hollywood films. Adler’s prose is exacting and full of surprises. Her reportage is rich and unfussy. The collection could stand on the basis of her intellect alone—and, in that regard, its velocity does not dip.

Nevertheless, the articles and essays in After the Tall Timber are not timely. They do not share an explicit thesis; they do not compose a political argument. And, in Adler’s hands, this is somehow not a shortcoming but a strength.

Consider “Radicalism in Debacle: The Palmer House” (1967), an essay on the national New Politics Convention. The Convention was designed to pull together liberal antiwar groups, radical civil rights activists, and members of the New Left: constituencies with the shared goals of ending racism, the war in Vietnam, and poverty.

The event was a catastrophe. Nearly half of the black attendees walked out to attend a separate conference of their own; Adler describes a group of white organizers’ decision-making process as “an orgy of confession about their childhood feelings toward blacks.” Adler’s essay documents the chaos of a political movement steeped in power differentials, and the persisting struggle between good intentions and paternalistic activism. It’s dark, but it’s also funny as hell. Adler:

A radical movement born out of a corruption of the vocabulary of civil rights—preempting the terms that belonged to a truly oppressed minority and applying them to the situation of some bored children committed to choosing what intellectual morsels they liked from the buffet of life at a middle-class educational institution in California—now luxuriated in the cool political vocabulary, while the urban civil-rights movement, having nearly abandoned its access to the power structure, thrashed about in local paroxysms of self-destruction.

Adler’s criticism of the radical left should not be taken as a sign of her own conservatism. She was left but not leftist, skeptical but always sincere; she eschewed agenda. Her politics and her journalism had guiding principles—human dignity, social equality, narrative truth—but they also weren’t restrictive. By maintaining her individualism, Adler was able to foster trust in her readers and keep a rare independence. As her infamous essay on the film critic Pauline Kael, now seen as a paragon of the hatchet-job genre—which pilloried Kael’s prose, condemning it for leaning on hyperbole, innuendo, and coercion—closes: “What really is at stake is not movies at all, but prose and the relationship between writers and readers, and of course art.”

The present collection is arguably about language: its use and abuse, its power and its failures. Language is the primary mode of ordering and understanding the world, and inevitably has a hand in dictating a moral common ground. Journalists frame discourse; writing demarcates an ethical scale.

“When words are used so cheaply,” Adler writes, “experience becomes surreal; acts are unhinged from consequences and all sense of personal responsibility is lost.” The distortion of language is the distortion of shared reality, and, for Adler, that’s unacceptable.

In an essay from 1970 (“Introduction, Toward A Radical Middle”), Adler argues that her generation “grew up separately, without a rhetoric.” They, the Silent Generation, are small, caught between two Americas: too young to have been involved in World War II or to fully absorb its traumas, but too old to have been wholly included in the cultural upheaval of the 1960s. “In a way, in culture and in politics,” Adler writes, “we are the last custodians of language—because of the books we read, and because history, in our time, has wrung so many changes on the meaning of terms, and we, having never generationally perpetrated anything, have no commitment to any distortion of them.” Adler’s newer, younger readers never had such luxury; in an age of performativity, rhetoric has reigned. People say nothing to everyone and say it all the time. In her work, Adler fights for language to be reclaimed, dusted off, and used with intention, clarity, and meaning.

In the current age—of content creation, of curation and aggregation, of distillations and explainers; digital media’s awkward teenage phase, let’s hope—there exists something of a hive mind: all buzz, no center. In this context, Adler’s arguments for political independence and linguistic intention seem terribly appealing. Her work is a reminder that there are reasons for writing and also of what writing can be. Adler trades in moments of quiet illumination, documenting people as they attempt to remove the abstractions of life through conversation and language.

In the days leading up to the Six-Day War, she spends time at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, watching the country ready itself for conflict. Scientists unroll tape to secure the Institute’s windows; children of faculty take first-aid courses. Families picnic on the sabbath, snacking beside military tents erected on farmland near the Gaza Strip. At the Institute, Adler captures a conversation between a group of professors and their families:

...an insufficiently hearty welcome was being accorded the volunteers who were coming into Israel from other countries to fight, to give blood, or to work. [The wife of a nuclear chemistry professor] felt there should at least be a poster to greet them at the airport. ‘It could be a tourist poster also,’ someone suggested. ‘See Israel While It Still Exists.’

Adler writes from a similarly sensitive vantage point in “The March for Non-Violence from Selma” (1965), and does it with a similar tone; she does not glamorize. Her portrait of the procession to Montgomery is high-anxiety, high-stakes, and high-octane, as tedious as it is moving. The march is disorganized. Rumors circulate. There are whispers of spies, snakes, the KKK. On the page Adler is everywhere at once, alert at all hours, darting from marcher to marcher, tent to tent. The piece is studded with dialogue, displaying the stilted misunderstandings between different factions of marchers and the tensions between the procession and the towns they passed through.“The marchers broke into a chant,” Adler writes. “‘What do you want?’ they shouted encouragingly to the blacks at the roadside. The blacks smiled, but they did not give the expected response—‘Freedom!’ The marchers had to supply that themselves.”

When Adler began writing more specifically about the media in the late ’90s —including a book, Gone, about the internal workings and interpersonal conflicts at The New Yorker that begins with a dramatic death knell: “As I write this, The New Yorker is dead”—her welcome in that world began to wear.

Adler’s points were valid, if uninvited. She railed against the inconsistencies, inaccuracies, indulgences, and vanities that she found to be increasingly visible in popular journalism, and deplored what she saw to be the degradation of institutional integrity within the media. Adler found specific trends particularly insidious: the reliance on anonymous sources (a loophole ripe for governmental exploitation; a method for “sources” to control the narrative), the rise of the “celebrity journalist,” and the erosion of factual reporting in favor of personal accounts. Adler took the New York Times to task for fussing over minor corrections, such as misspellings, while it ignored its own fostering of broader inaccuracies and prejudices. She deemed the minor corrections of misspelled surnames “the Times’s substitute for conscience, and the basis of its assurance to readers that in every other respect it was an accurate paper... worthy of their trust.”

It’s hard not to see why, at the beginning of this new century, Adler found herself with more enemies than supporters; it also seems important to note, if only for the frame it provides. Journalism, now, is more nebulous, and industry whistleblowers can even find institutional support, often in the form of other media companies.

Adler’s shunning was industry-political. It was personal. And her missteps truly aren’t relevant anymore. Adler meant something different to people thirty years ago, but most of her critics from the ’80s and ’90s have moved on. Many of her subjects are dead. In the last decade, readers and publications have forgiven journalists for worse transgressions—Jonah Lehrer’s relative redemption comes immediately to mind—and careers have been buried over less.

Renata Adler was a journalist at the top of her game, working for the country’s most well-respected publications. She was a woman working in a historically male-dominated industry who played by her own rules. Adler burned bridges and leveraged dissent with aims more significant than elevating her own byline, fighting for the enterprise of journalism itself—its integrity and its respect. This eventually saw her driven out: a loss for readers, a loss for politics, a loss for journalism, a loss for the art of writing. So now, it’s no small pleasure to see her work back in the light.

There is a photograph of Renata Adler, taken by Richard Avedon in 1978 on a vacation in St. Martin. She’s willowy and alert, vulnerable but steeled. Her eyes are wide-set and heavy-lidded, and her signature braid snakes across one shoulder and down the front of her shirt, unraveling mid-waist. She is striking.

In twenty-first century online literary circles, where photographs of Joan Didion are circulated with the same zeal as actual quotations from “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” this sort of image is a fetish. (Didion and Adler have many of the same fans; they are prone to similarly devoted behaviors.) When Speedboat and Pitch Dark were reissued, Avedon’s photograph was harmonious with the tenor of both—and for some, it was even synonymous. It seems appropriate, now, to see it as the cover of After the Tall Timber: Adler standing tall and defiant.

Rediscovering Adler’s nonfiction feels right. After the Tall Timber feels like an extension of Speedboat and Pitch Dark, except here there’s the added urgency and political resonance of narrative nonfiction. Adler captures the dark comedy of being human—the social, emotional, and physical inventiveness necessary for our continued survival.

We live in a time of crisis, anxiety, and dread; we always have. As a new generation sifts through its mixed inheritance of politics, rhetoric, and written analysis, Adler’s work could serve as a guidepost. It’s “Black Lives Matter”, not “All Lives Matter.” The difference between an occupation and a settlement depends on who is speaking. These distinctions are significant; their conflation, irresponsible.

Adler was attuned to the repercussions of using language that is symbolic, that doesn't hold weight, that perpetuates unjust narratives. It was the cornerstone of her work—she said exactly what she meant and held others to her standards. Where Adler’s novels are documents of interiority, After the Tall Timber is a collection concerned with the damages of the larger world. Traveling from her fiction to her nonfiction is only a frame shift: The scale is greater, the stakes higher. Yet the method is the same. Either way, her impact is felt.