A strange thing happened on the internet a few days ago. Explaining why he’d deleted a post by one of his writers that was critical of one of BuzzFeed’s advertisers, editor Ben Smith announced: “We are trying not to do hot takes.” Calling something a “hot take” is an increasingly popular way to dismiss the value of a piece of writing—bad, stupid, disingenuous, or some other subset of the broad category of “bullshit.” You would think the internet would have cheered Smith on—there were about 500 tweets mocking one hot take or another on that Friday alone. But that did not happen. Instead, the internet rebelled: The post was not, in fact, a hot take. Smith’s assertion that the post was bullshit was itself bullshit. He eventually capitulated and reinstated the post, but pledged to keep thinking about “the place of personal opinion on the site.”

Slate editor-in-chief Julia Turner responded with a stirring defense of “the most unfashionable thing in journalism.” Because the internet offers so much information, “readers are more reliant than ever on commentators who can analyze and interpret it,” to explain what it all means. Just because some commentary is bad doesn’t mean it’s all useless—in other words, not every take is a hot take.

It felt, all of a sudden, like the fate of journalism in the digital era rested on a collective judgement on the hot take. It may seem like the hot take is as old as time, or as old as Twitter, maybe. But despite its ubiquity, the term is a surprisingly recent invention. I went out in search of an answer to this question, interviewing countless (12) hot take scholars and scouring the internet for evidence of the hot take’s true ancestry. Here is what I found.

[A note about sourcing: Alert readers will notice that almost everyone quoted in this article is a dude. When I searched for hot take scholars, I initially could only think of dudes; when I asked them to name other hot take scholars, those dudes named dudes. When I suggested one female writer to a male source, he said, “Yeah, she definitely wants to be part of the boys club.” When I checked Urban Dictionary for its hot take definition, I found the entry was written by—and I think it’s fair to read symbolism into this—a user named Penis Armada.]

What is a hot take?

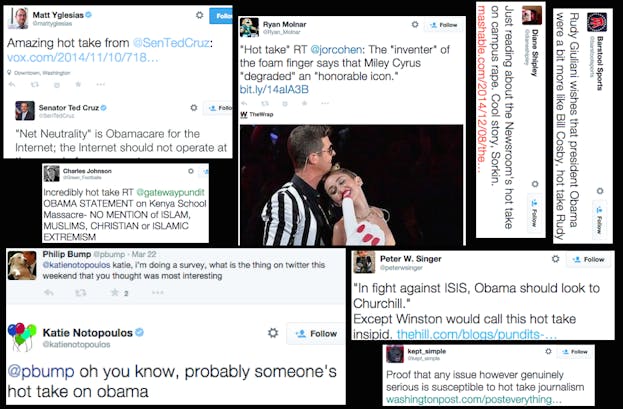

As the term “hot take” has become more popular, its essence has been diluted. It’s often used to dismiss an assertion you don’t agree with. But the true hot take is a piece of opinion journalism hastily written in a scolding tone, often by older men (see sourcing note above) who have achieved enough status in media that they don’t have to work so hard anymore. There’s a “just telling it like it is” attitude, even if, according to the best available data, it is not like that at all. “It’s a useful phrase to describe a scourge that became a scourge almost as quickly as it became widespread,” Gawker editor-in-chief Max Read said. “It’s the perfect media phrase because it allows the person who uses it to 1) dismiss something 2) contemptuously using 3) a bit of insidery jargon.”

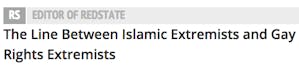

Salon’s Simon Maloy, who makes a lot of hot take jokes, said, “a hot take is a piece of deliberately provocative commentary that is based almost entirely on shallow moralizing.” Maloy points to Erick Erickson, editor of the influential conservative site RedState.com. An essential Erickson hot take came in 2013, when he argued that working moms are bad for kids because male animals tend to dominate female ones. When criticized, Erickson responded that it was “a matter of fact” that kids with moms who stay home are better off. It was not a fact. In February, Erickson argued that gay rights activists, who want to make it illegal for businesses to discriminate against gays, have a lot in common with ISIS, which crucifies children. “The divide between Islamic extremists and gay rights extremists is at death,” Erickson asserted. “The gay rights activists who yell ‘bigot’ at those who disagree with them are the Imams of America’s cultural ghetto.”

Tomás Ríos, editor-in-chief of Vice Sports, points to liberalish Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen. “The thing about a lot of hot take writers is they just kind of burn out over time,” Ríos said. Instead, “Cohen has just somehow consistently managed to find a tiny island of personal absurdity that only he can occupy. So you know, all credit to him.” Cohen suggested in 2013 that people with “conventional views” “must repress a gag reflex” when they see the interracial family of the mayor of New York.

For a take to be truly hot, “it’s not necessarily intentionally contrarian, but it is written in such a way that you can tell it’s a bit of a troll,” The Washington Post’s Philip Bump said. “There’s an implied artificiality to it. And also, it’s a crappy piece.”

Rusty Foster, who writes the Today in Tabs newsletter, said the “prototype hot take” is when news breaks, and then “somebody will rush out an opinion piece a couple hours later that comes to some really grand conclusions based on this one thing that happened that maybe we don’t even have all the facts about yet.”

Where did the hot take come from?

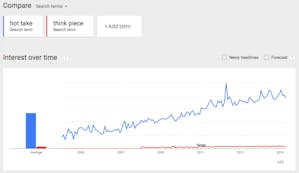

A startlingly high number of “hot take” users don’t know its origin or age. “I realized that it feels like it’s always been, but it hasn’t always been,” Foster said. Dave Weigel, a Bloomberg Politics reporter and major hot take denouncer, sounded surprised when he searched his own Twitter history and found his first #hottakes tweet dated back only to October 2014. Gawker editor Alex Pareene said the political Twitter world embraced hot take last year, “though it definitely feels older.”

The hot take—both the phrase and the thing it describes—has a long history in sports, as Ríos explained in an August 2013 history of bad sports writing for Pacific Standard. Sports writing in the 1920s and 1930s was dominated by mythmakers like Grantland Rice (the namesake of Bill Simmons’s sports-entertainment-opinion site), who used purple prose to turn athletes into godlike heroes. Then, in the 1960s and 1970s, sports writers began wrestling with larger societal problems in their columns. “Rather than manufacture heroes out of athletes,” Ríos wrote, stalwart New York Daily News sports columnist Dick Young “applied the standards of heroes to athletes and promptly eviscerated anyone who fell short of his impossible ideal.” The athlete wasn’t the hero; the columnist was.

The phrase “hot take” seems to have reached critical mass in the sports world sometime in 2012, amid a flood of Tim Tebow coverage, according to Caitlin Kelly, a New Yorker web producer. (For a while, Tebow was to the sports internet as Kim Kardashian is to the rest of the whole internet.) That was also the year Eric Koreen, a basketball reporter for the Toronto-based National Post, tweeted one of the earliest modern uses of “hot take.”

The secret thing about Call Me Maybe is that it’s a great pop song. #RealTalk #TruthToPower #HotTake

— Eric Koreen (@ekoreen) November 2, 2012

Koreen said the notion could perhaps be traced to the baseball blog Fire Joe Morgan, which “railed against columnists or announcers supporting their own long-held beliefs with flimsy evidence that defied math,” even if the blog’s writers never used the term “hot take.” Morgan was a baseball player in the 1970s who became a commentator for NBC Sports and ESPN in the 1990s and 2000s. Morgan’s analysis came from his gut at a time when fans increasingly wanted analysis that at least acknowleged the validity of advanced statistics. In a 2005 interview with Tommy Craggs (now the executive editor of Gawker Media) for SF Weekly, Morgan explained why he hated Moneyball, the Michael Lewis book about using statistics in sports management. It is the very essence of hot-take thinking:

Why would I wanna read a book about a computer, that gives computer numbers? ...

Why would I wanna read the book? All I’m saying is, I see a game every day. I watch baseball every day. I have a better understanding about why things happen than the computer, because the computer only tells you what you put in it. I could make that computer say what I wanted it to say, if I put the right things in there. ... The computer is only as good as what you put in it. How do you think we got Enron?

Sure enough, if you scan the Fire Joe Morgan archives, you can see the beginnings of the anti-hot-take movement that would eventually rally the new media world. An excerpt from a post from January 2008:

Here’s a little ditty entitled “Attitude Can’t Just Be a Platitude for Sox,” by legendary comic actor Dave van Dyck (The Dave van Dyck Show, Diagnosis: Murder.) The thesis is that what the 2007 Chicago White Sox lacked was not “hitting” or “pitching” or any of those other pesky “tangibles,” but rather: a certain je ne sais quoi.

You can see a parallel to this in the political writing world, like, say, in the Joe Scarborough vs. Nate Silver fight of 2012. Silver held the view that polling data showed President Obama as the overwhelming favorite to win re-election over Mitt Romney, and Scarborough argued but but but the race feeeeels close. The day before the 2012 election, Peggy Noonan offered this hot take, “While everyone is looking at the polls and the storm, Romney’s slipping into the presidency.” Why? Well, for one, “In Florida a few weeks ago I saw Romney signs, not Obama ones.”

How did the hot take spread from sports?

It’s hard to conceive of a thing until you name it. “There are certain words,” Radiolab host Jad Abumrad explained in a 2010 episode about language, “that don’t just give you a name for something; somehow they give you access to a concept that would otherwise be really hard to get or even talk about. … It’s really hard to talk about thoughts, without the word ‘thoughts.’ Or what is time without the word ‘time?’ It’s a really freaking hard concept. These words are like bridges. Somehow they get you to some new mental place that otherwise you’d be cut off from.”

“I remember the first time I think I ever sort of deconstructed a take was, there was a profile of Chris Matthews that I did in 2008,” The New York Times Magazine’s Mark Leibovich said of the MSNBC host. “We were in a spin room and basically it was kind of a flea market for people giving and taking takes.” Leibovich had written at the time, “Matthews seemed compelled to give his ‘take,’ which is how he describes his job each night at 5 and 7, Eastern time, on ‘Hardball’—‘giving my take.’ … He can also be unsparing in his criticism of those who run afoul of his ‘take.’” Leibovich said now, “That’s obviously moved seamlessly to Twitter, which is like Take Central.”

#IranTalks (via @darth) pic.twitter.com/O5U2Wb0exe

— Elise Foley (@elisefoley) April 2, 2015

“Though ‘my take on ___’ is as old as the hills, the ironic ‘sizzling hot take’ or what-have-you is, I’m pretty sure, from people making fun of ESPN [”Around the Horn”] sports bros,” explained Pareene, long known for his takedowns of hot take writers. “My theory has always been that political writers either wish they were sports writers or music writers so there is a similar sensibility there—‘I’m saying what no one else has the guts to.’”

Think of the movie Contagion, in which a bat virus merged with a pig virus to infect Gwyneth Paltrow and then ravage the United States. “Way back before ‘hot takes’ were in politics, political reporters would link to each other’s work and earnestly say ‘smart take,’” Pareene said, noting a 2013 Gawker post titled “Word Terrorism: When ‘Smart Takes’ Aren’t.” Once that phrase became sarcastic, “the smart take married the sports hot take, and the rest was history.”

“For a while ‘smart take’ was the phrase used to indict a piece for being stupid and conceived for traffic,” Weigel said. “Someone pointed out to me that ‘smart’ implies that someone sat down with a quill and glass of brandy or whatever it is smart people use when they’re writing and really wanted to show something with what is essentially stupid. Whereas the ‘hot take,’ I think, or at least the way I have interpreted it, implies that the author wants traffic and doesn’t give a crap about whether the take makes sense.” The evolution makes sense. Ríos said, “One of the only arenas in all of culture that can compete with sports in its tendency to mythologize the participants is politics.”

And it’s not a coincidence that hot take writers in sports and politics look a lot alike. “The realm of the hot take has always been the realm of the male, specifically the white male,” Ríos said. “National sports columnists are overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly male. The reason you can be successful writing hot takes is not that you have controversial opinions, it’s actually because your opinions are quite milquetoast to a certain brand of consumer.”

Hot take parodies skewer the banal presented as something brave. At Grantland, Andrew Sharp writes a satirical #HOTSPORTSTAKES column. Last year, when Richard Sherman, a really good football player, said on TV he was really good at football, outraged hot takes exploded across the internet. Sharp wrote, “The guy who turns sportsmanship into a punch line is bad, but the culture that laughs along with him is far scarier.”

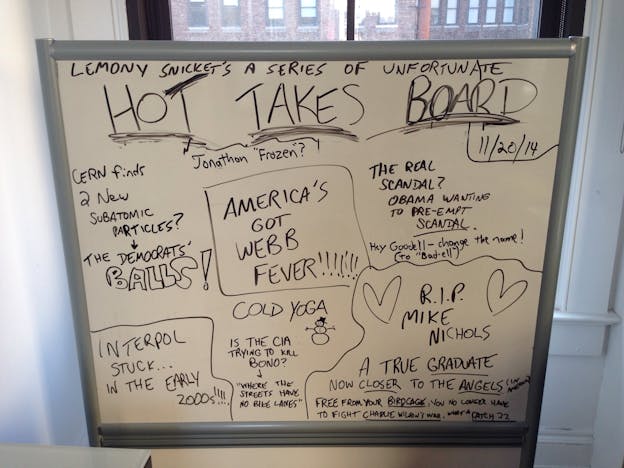

Last year, Pareene and I worked for the failed political satire site Racket, where we launched a protest blog called Racket Teen. Our most popular posts were usually the daily Hot Takes Board, a collection of headlines that combined self-righteousness with idiocy:

The driving force behind the board was our colleague Michael Pielocik, an outsider-expert on hot takes, once as a writer for The Onion and now in late-night comedy. Pielocik emailed:

Whether you call it a “hot take” or whatever, everyone really is trying to point out something that has not been pointed out a million times before. But a lot of writers also want it to get clicks and have their work read and keep their jobs, so you have to put topical #viral stuff in there too. So writing a headline like “Is Autism the New Gangnam Style” or “What ‘Game of Thrones’ Teaches Us About Ferguson” or whatever, it makes a point that probably hasn’t been made before... but that might be because it’s dumb as hell.

What will become of the hot take?

“Mark Leibovich—I hate to say a sentence like this now, but he had a tweet that really stuck with me,” Weigel said. “He, like a bunch of veteran reporters, I think, is really tired of how dumb a lot of internet commentary has gotten, and he had this tweet years ago saying, ‘We’re drowning in takes… enough with the fucking takes.’”

So many people are giving us their “take” on this...We are a nation drowning in “takes!”

— Mark Leibovich (@MarkLeibovich) May 9, 2012

The takes have not stopped coming since that tweet. As John Herrman argued at The Awl last year, sometimes a story, like stolen celebrity nudes, “generates an enormous surplus of attention, much more than news can meet.” Demand for new information about the nudes outstrips supply. And so the news industry offers the take.

Everyone with an outlet—or, really, everyone, since the great democratization of Take distribution tools coaxed previously private Takes out from bars and dining rooms and into the harsh sunlight—found themselves under the spell of that horrible force that newspaper columnists feel every week, the one that eventually ruins every last one: the dreadful pull of a guaranteed audience.

Rebecca Greenfield, a writer most recently at Fast Company who was my colleague at the now defunct Atlantic Wire, explained that the site was a take innovator out of necessity. “Hot take is an evolution of the blog post… it was easy to block quote and write a clever headline, so the Wire had to do one better with the same amount of resources (none).” The take industry is only growing more efficient at supplying enough takes to meet reader demand. Surveying the wave of Apple Watch reviews, Foster began Thursday’s edition of his Today in Tabs newsletter, “The second day of the Take Cycle is usually my favorite. I sometimes ignore a whole first day’s worth of takes because the second day’s are always better (slash worse).”

What allows hot takes to spread also makes it easier to avoid them. Ríos doesn’t read hot takes anymore, thanks to Twitter: “It’s always pretty obvious when someone is genuinely saying, ‘Hey, this is a really good piece, everyone should read it,’ and ‘Hey, this is a really shitty piece, and I hate it, and now I’m going to introduce it into your life so that you can hate it as much as I do.’”

And the phrase “hot take”? It could be doomed.

“It probably has a few more months,” Foster said. The phrase is showing signs of stress, as in the BuzzFeed incident. “The purgatory in between when something becomes a cliché and when it dies is some kind of ironic treatment of it,” Leibovich said. “Twitter is in some ways the race to irony.” Does it kill all jokes? “You have to be in on the joke to be aware that the joke is a cliche or that the joke has been killed.” Bump said, “I think Twitter is like one of those chair-testing machines they have on display at Ikea. You put a joke in and Twitter beats the shit out of it and then you know how resilient the joke is and also the joke has been smashed into dumb pieces and only idiots would want to use it.”