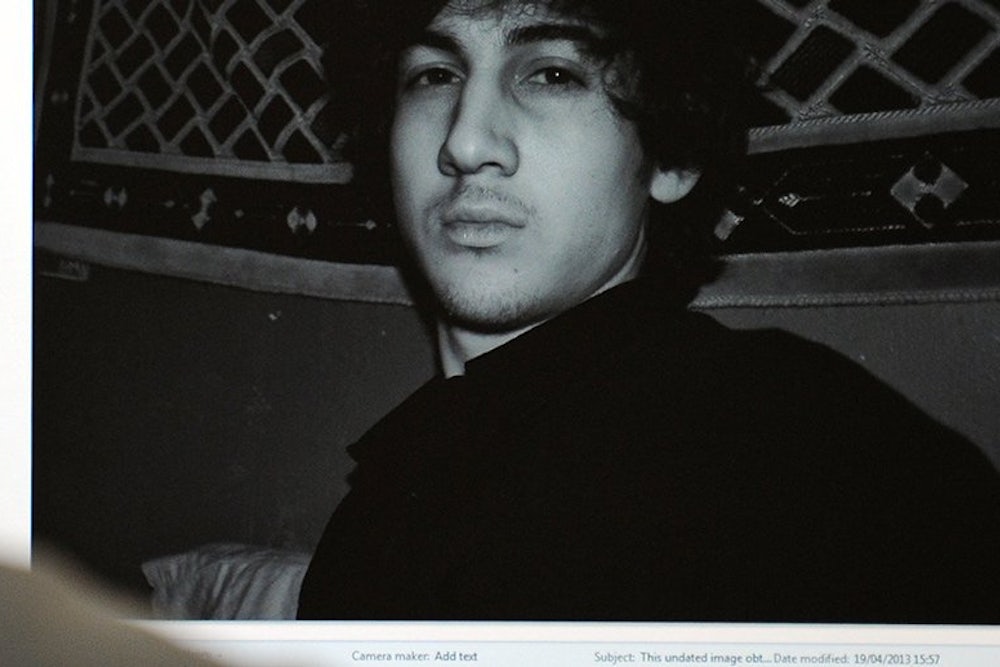

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the young man arrested in the spring of 2013 for the Boston Marathon bombings that killed three and injured 280, has been found guilty of all 30 counts against him. Seventeen of those charges carry the possibility of the death penalty, which Tsarnaev will face as the sentencing phase of his trial begins as early as next week.

It was around this time in 2013 that I followed Tsarnaev’s pursuit on the news in my Waltham, Massachusetts apartment. Like most people living in the area, I was terrified of him and his older brother, Tamerlan, not sure who they were or what they were capable of. I watched police pour into Watertown, the Boston suburb adjacent to mine, and was glued to the television as tidy New England homes were evacuated, their rooftops scaled by armed men. By that point, Tamerlan was dead, having been run over by an SUV his brother drove, and Tsarnaev was holed up in a winterized motorboat. If someone had asked me then what should be done with him once caught, I would have said he should be put to death. I was angry, and I was afraid.

But things change.

Two years on, it appears that those nearest to the bombings do not desire Tsarnaev’s execution. In the fall of 2013, a Boston Globe poll found that 57 percent of Bostonians favored life in prison for Tsarnaev, with only 33 percent preferring death. A poll released a few weeks ago by WBUR, Boston’s NPR outpost, found support for life in prison had grown to 62 percent, while those calling for the death penalty fell to 27 percent—even though the poll was conducted during the highly publicized trial, when the grim details of that day became daily news yet again. As the president of the survey firm told the The New York Times, “It seems voters stuck to their core values.” But the Bostonians who oppose killing Tsarnaev are not alone.

Pope Francis recently called the death penalty “an offense against the inviolability of life and the dignity of the human person. When the death penalty is applied, it is not for a current act of oppression, but rather for an act committed in the past. It is also applied to persons whose current ability to cause harm is not current, as it has been neutralized—they are already deprived of their liberty.” Four Massachusetts Catholic bishops quoted those remarks in a statement Tuesday appealing to jurors to let Tsarnaev live, adding, “The defendant in this case has been neutralized and will never again have the ability to cause harm. Because of this, we, the Catholic Bishops of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, believe that society can do better than the death penalty.”

For a heavily Catholic city like Boston, that admonition has to hit home. And it should: Pope Francis and the bishops following his lead are precisely right.

There is no good reason to kill Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. He was dangerous insofar as he had access to weapons and leadership, and deprived of both he wound up huddled in the fetal position under a bullet-shredded boat tarp. Even if you imagine him to be doggedly committed to wreaking havoc, he is only 21 years old; condemned to life in prison, he may yet turn himself around. The death penalty, meanwhile, is irreversible: If Tsarnaev is put to death sometime down the line, after years of delays and appeals, it is possible that we will be executing someone who has very little in common with the person who participated in the horrific attacks at the Boston Marathon finish line.

Nonetheless, Tsarnaev’s trial might ultimately conclude with his death. No administration wants to be the one that went soft on a terrorist, which is why the death penalty is on the table despite the fact that Massachusetts effectively outlawed it in 1984. If Tsarnaev's jurors reflect the moral sensibilities of Boston at large, they will refuse to kill him, because doing so would protect no one and restore nothing, to him or anyone else. It would, in fact, undo the possibility of his ever making any kind of amends to the lives he shattered, the families he crushed, the community he ruptured, the security and comfort he destroyed. Death is a void, and an ugly stop. Its finality is a source of closure only for the dead.

Those not persuaded by mercy, meanwhile, might be persuaded by the nightmare I dimly entertained the evening Tsarnaev was apprehended, when a grainy photograph of his bloody face flashed across my television screen. I think the picture must have struck some as triumphant, but it reminded me of the icons of martyred saints I have seen, wounded and humiliated but victorious in their own way. The word martyr, after all, comes from mártus, meaning “witness.” However we deal with Tsarnaev as a nation will be viewed by the entire world, and there are many angry young people who may see themselves in Tsarnaev, as half-baked as his rebellion was.

It would be better not to give such people an emblem for their cause, especially given that Tsarnaev’s original crime was, in his thinking, an act of revenge. At some point the cycle simply has to stop, and with Tsarnaev, the jurors in Boston have a chance to contribute to that effort.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that 11 of the charges against Tsarnaev carry the possibility of the death penalty. Seventeen of the charges do.