In February, a Bureau of Land Management field office in Cedar City, Utah, released a report assessing the environmental impact of leasing 41,000 acres of federal land in Beaver County for oil and gas development. One sentence in particular, in the final appendix of the 69-page document, infuriated environmentalists. In a reply to a comment letter submitted by the nonprofit WildEarth Guardians, the report stated, "At the present time, there is a substantial amount of professional disagreement and uncertainty as to what impacts greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have on climate and, as a result, it is not possible to determine what social costs, if any, could be caused by emissions of GHGs."

Most climate scientists, of course, would disagree that there's any "uncertainty" surrounding the fact that greenhouse gases cause climate change. The BLM's boss would disagree, too. Last month, President Barack Obama ordered federal agencies—including the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), which oversees the BLM—to cut greenhouse gas emissions over the next decade by 40 percent from their 2008 levels.

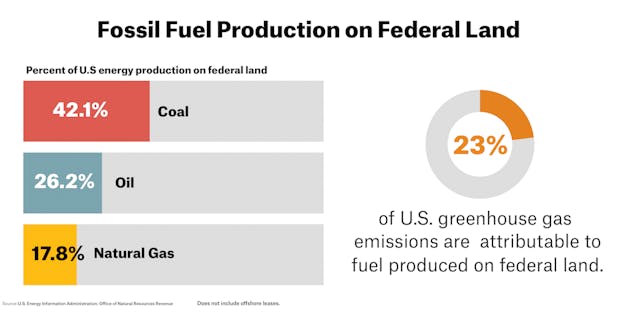

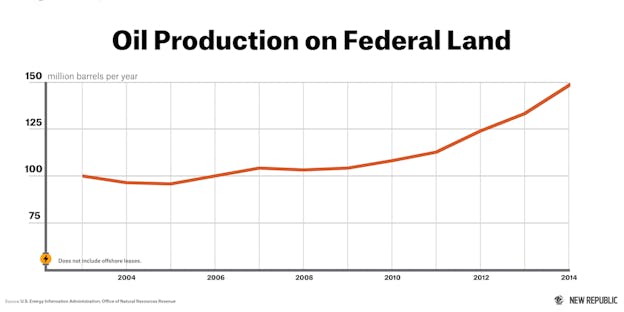

No government agency will have a tougher time meeting that deadline than the DOI, which manages more than 500 million acres of lands across the country—bigger than Texas, California, and Alaska combined—and another 1.7 billion acres offshore. The fossil fuel energy that’s developed from these lands could be responsible for as much as 24 percent of the U.S.’s climate change emissions; the lands account for 40 percent of the nation’s coal production (concentrated in the Wyoming and Montana's Powder River Basin), and 23 percent and 16 percent of oil and natural gas respectively. Federals lands also include national forests and pastures, which help absorb greenhouse gas emissions, but overall the lands contribute nearly four-and-a-half times more carbon to the atmosphere than they absorb.

This makes the Department of Interior crucial to the future of climate change action, but the agency—the BLM in particular—only haphazardly considers climate change in its everyday decisions. How can the administration lead by example when one of its departments is responsible for nearly a quarter of all U.S. emissions—and seems to have no intention of reducing fossil-fuel development? It's a question more and more environmentalists are demanding that Obama answer.

To the WildEarth Guardians, a Western conservation group fighting many of the BLM leases, the statement that "there is a substantial amount of professional disagreement and uncertainty as to what impacts greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have on climate" sounded a lot like climate-change denial.

“This blatant rejection of settled science is a dangerous and distressing sign of the lengths the Interior Department is going to cater to the fossil fuel industry,” WildEarth Guardians' Jeremy Nichols said in a statement.

But the BLM report may not be outright denial. What the BLM meant is that it doesn't have the tools or capacity to assess what a relatively small fossil fuel project will have on global greenhouse gas emissions.

Asked about its decision not to consider greenhouse gasses in several assessments of BLM leases, Jessica Kershaw, a spokeswoman with the Department of Interior, emphasized the importance of coal in the nation's energy portfolio. "As part of the Obama Administration’s all-of-the-above energy strategy, the Department of the Interior and specifically the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is committed to the safe and responsible development of both traditional and renewable energy resources on public lands," she said. "The BLM also recognizes that coal is a key component of America’s comprehensive energy portfolio and the nation’s economy and works to ensure that the development of coal is done in an environmentally safe and responsible manner."

The Cedar City Field Office's environmental assessment isn’t an isolated circumstance. The government has spent four years deciding whether to lease 3,500 acres of public lands to Alton Coal in southern Utah, mere miles from the popular Bryce Canyon National Park. The site is far from a railroad line, so Alton will have to burn additional fossil fuels to truck the coal out (on roads frequented by tourists, no less). The BLM also declined to assess greenhouse gasses for that project, stating that the “existing climate prediction models are not at a scale sufficient to estimate potential impacts of climate change within the analysis area.”

When and how BLM considers greenhouse gasses is seemingly random. Anecdotally, some offices consider the estimated impact, others don’t, and it varies by state: For a Wright Area Coal lease assessment in the Wyoming side of the Powder River Basin, BLM went on at great length about the environmental issues and thoroughly explained its process for assessing emissions—the same step that Utah’s office said would be impossible.

A June 2013 report by the Interior’s inspector general suggested the BLM's decentralized structure was partly to blame for the inconsistency.

“[A]lthough the Washington Office manages the coal program, it does not directly control the program in the many State and field offices that oversee coal leases,” the report stated. “Without strong, centralized management, State and field office personnel may interpret official standards, processes and procedures inconsistently.”

Fixing these issues will require serious reform, which Interior Secretary Sally Jewell has promised—to a point.

Seven leases are currently pending in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin and in Montana, as the BLM decides whether to open the land to mining. According to WildEarth Guardians, those leases could amount to many as 3.6 billion tons of mined coal, on top of the 2.2 billion tons of coal already leased since Obama took office. Some of that coal is burned at U.S. power plants, and some of it is exported to satisfy rising demand abroad, especially in Asia; it all contributes equally to global warming.

There are ways to address the carbon impact of fossil-fuel development on federal lands that don't require shutting down mining. The BLM should consider the social cost of carbon in its decision to lease the land in the first place, in deciding how much to charge for land, and what to require in royalties (fees paid on the value of the coal being mined). The government estimates the social cost at $37 a ton, thought other estimates put that number as high as $200. By adding in the true cost of carbon to both royalties and lease bidding, BLM would take a fairly radical departure from the way it currently does business.

Based on 2014 data, coal from the Powder River Basin sells for the absurdly low price of $13 per ton of coal, far below coal's true environmental cost. Royalty payments are equally low, at just $1.63 per ton. If the true cost of carbon were factored in, coal should sell for around $62 per ton, more than four times the current amount. Tracts of land that are far from efficient transportation would be considered too environmentally costly for companies to develop.

Groups like WildEarth Guardians, Earthjustice, and Sierra Club have brought lawsuits on the BLM for not considering the social cost of carbon, and just won one at the West Elk Coal Mine in Colorado, but lawsuits make for slow progress. Instead, the Obama administration should provide the BLM with clear guidance on assessing the greenhouse gas implications from these projects. Because such guidance doesn't exist, these decisions are made in BLM offices across the country. “The bigger problem is they’ve not evolved to the point of actually using [carbon emissions] in the decision making process in any way,” Mark Squillace, a University of Colorado professor and expert on natural resources, said in an interview.

Royalties are another area prime for reform. Taxpayers have effectively subsidized coal to the tune of $50 billion because of accounting tricks companies use to pay much less than the 8-12.5 percent of royalty fees on its revenue. Lastly, BLM's leasing process isn't as “competitive” as it claims. “One of the problems of not having a competitive market is they’ve essentially let coal companies decide what the market price of coal has been,” Squillace said. At times, in the 1990s, the market cost was as low as 11 cents per ton of coal. Today, it is about $1 per ton. Sometimes one company is the only bidder on a tract of land up for lease, so the lowball offer stands.

Existing laws may make reform difficult. The Mineral Leasing Act requires each state BLM office to make a lease sale every three months. While Squillace argues that the Federal Coal Leasing Act of 1976 never intended BLM to take such a passive approach in the leasing process, the coal industry essentially now the drives decisions and demand for mining public lands.

Jewell, the Interior secretary, promised broad reform in a March speech. “Helping our nation cut carbon pollution should inform our decisions about where we develop, how we develop, and what we develop,” she said, adding that the DOI would "make energy development safer and more environmentally sound," evaluate how much companies pay the government for land, and improve how the department evaluates climate change in lease sales.

But she opted for vague language over concrete solutions.

"I share the president’s belief that America should lead the world on energy, climate, and conservation," she said. "And to accomplish this, we need to encourage innovation, provide clear rules of the road, and make balanced decisions."

The Interior Department undoubtedly has a difficult job in balancing the sometimes-competing priorities of energy development and conservation. That same tension was apparent in Jewell's rhetoric. She noted her appreciation of “the importance of the oil and gas sector," saying she's "committed to its ongoing success." And to be clear: She signaled no intention to reduce the development of fossil fuels on federal lands.

"If they really started to come clean to the American public, not only how much emissions come from public coal and gas, but they’d have to show they’re saddling the public with an immense climate debt,” Nichols, of WildEarth Guardians, said. He sees many roadblocks to reforming the BLM. “Culturally it’s not what they’re about and politically they’re afraid of the ramifications.”