The VIDA: Women in Literary Arts annual count is brilliantly simple: It’s just a bunch of charts showing the percentage of books reviewers, reviewed authors, and total bylines in major literary publications are women. It’s not about the qualms women have when pitching articles, nor is it about which subject areas are male- or female-dominated. It’s about hard, cold, facts. And VIDA's 2014 data, released Tuesday, includes even more facts: the race of the female writers it surveys.

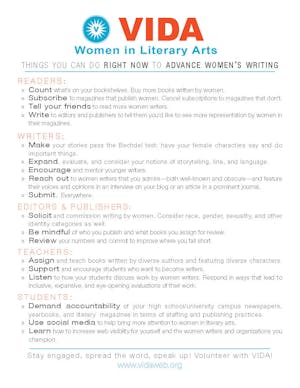

VIDA co-founder Erin Belieu told the Guardian that the project’s “goal has always been consciousness not quotas. Art doesn’t get made by quotas and some years it’s going to go forward, some years it’s going to slide back a little bit, but over time what we hope for is a shift in consciousness.” But VIDA doesn’t entirely steer clear of practical advocacy. A digital “handout” they include with the new survey, “Things you can do right now to advance women’s writing,” which is mostly advice about how writers, editors, readers and others can support female writers (buying their books, promoting them on social media, etc.). But two tips directed at writers take a different tack: "Make your stories pass the Bechdel test: have your female characters say and do important things." And then, "Expand, evaluate, and consider your notions of storytelling, line, and language."

The first is a straightforward call for feminist fiction. The Bechdel test, as Charlie Jane Anders explains at io9, comes from a comic by Alison Bechdel, in which a character says, “I only go to a movie if it satisfies three basic requirements. One, it has to have at least two women in it…who, two, talk to each other about, three, something besides a man.” The VIDA advice goes further than that; these fictional women and girls must “say and do important things.”

As for the second, I’m not entirely sure what it means. My last formal creative-writing education was in high school, where I wrote fiction about teenage girls talking about boys. But it sounds like generic advice to write thoughtfully, but the context would suggest it’s also a suggestion to somehow take gender into account when writing.

These tips bring up interesting questions of what it means to advocate for feminism in literature. Is it a matter of opening up a professional field? Or does the writing itself need to be pro-woman, whatever that may mean?

While I strongly support VIDA’s efforts in the former area, I think it was a mistake for them to venture into the latter. Constructing limits—albeit just suggested ones—on literary creativity isn’t helpful to VIDA’s broader mission, and may even be detrimental.

The most glaring problem is the suggestion that female characters must “say and do important things.” Many of the best fictional characters, regardless of gender, don’t meet that standard. (What did Alexander Portnoy say or do that was so important? What he did to that liver was memorable, but not particularly admirable, and it probably wouldn’t pass a gender-reversed version of the Bechdel test.) The “strong female characters” trope has elicited many eye-rolls over the years, enough so that the feminist default is if anything a celebration of flawed ones. And the notion that fiction must be about something “important” has a way of only arising if the person writing that fiction is not a white man. Authors who aren’t white men not only face a higher burden when it comes to having their work treated as literary, but also get steered towards identity-driven topics. Ben Okri argues in the Guardian that, while white authors (he includes female ones) get to write about all sorts of topics, “black and African writers are read for their novels about slavery, colonialism, poverty, civil wars, imprisonment, female circumcision—in short, for subjects that reflect the troubles of Africa and black people as perceived by the rest of the world.” And yet, Okri adds:

It is a curious fact that the greatest short stories do not have, on the whole, the greatest or the heaviest of subjects. By this I mean that the subject is not what is most important about them. Rather, it is the way they are written, the oblique way in which they illuminate something significant. Their overt subject might seem slight but leads, through the indirect mirror of art, to profound and unforgettable places. The overwhelming subject makes for too much directness. This leaves no place for the imagination, for the interpretative matrix of the mind. Great literature is almost always indirect.

It’s a mistake to ask fiction writers—male or female—to make their female characters behave in “important” ways. A focus on “important” stories, ones with major historical or political content, rules out the smaller-scale domestic or interpersonal stories that make for such great fiction. The issue that needs addressing isn’t that there aren’t enough novels about female soldiers and activists. It’s that, as Katie Roiphe pointed out at Slate, the small-stakes narratives coming from female authors aren’t treated as serious literature. This is a problem for criticism; the answer isn’t for authors to seek out different material.

The Bechdel-test issue is slightly more complicated. It’s easy enough to dismiss the request that female characters be powerful or likeable, but less obvious why it would be a problem to demand more female characters who aren't defined by what they're doing with, or saying about, men. In the abstract, it sounds like an admirable goal.

But fiction isn’t about meeting admirable goals. Or, rather, the admirable goal that’s relevant here is the removal of obstacles to professional parity. The focus should be on authors, not characters. If the main issues VIDA's addressing—which are essentially employment concerns—improve, the character-representation issues would likely be addressed, given how much writing is based on personal experience. Shaming writers into creating VIDA-approved stories will only yield unexceptional writing.