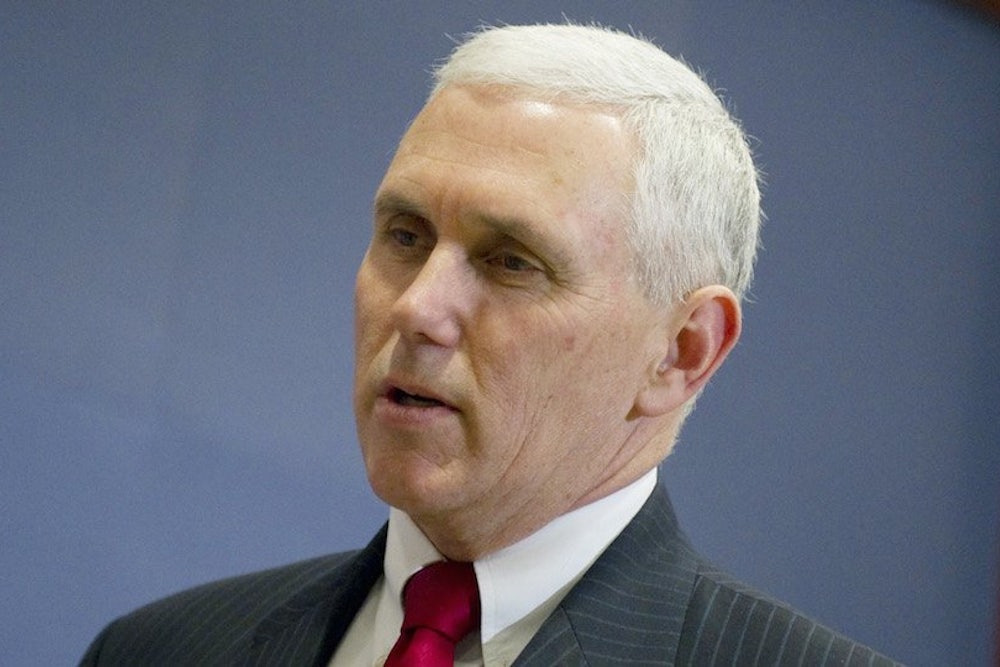

When Arizona's then-Governor Jan Brewer vetoed legislation last February to protect religious individuals and business owners who deny services to gays and lesbians, she lost favor with many Christian conservatives. But as the public backlash grows against Indiana, whose governor, Mike Pence, just signed a similar "religious freeom" law, Brewer now looks prescient.

In a statement accompanying her veto, she wrote, “I sincerely believe that Senate Bill 1062 has the potential to create more problems than it purports to solve.” That's exactly what's happening in Indiana: thousands of protesters, and, likely, a loss of business. You can’t claim to be a pro-growth conservative and then intentionally make your state the epicenter of a massive boycott, which explains why Pence is now promising to "clarify" the law.

Now comes the backlash to the backlash, in which conservatives—including most of the major presumptive Republican candidates for president—insist that the Indiana statute and similar efforts are merely intended to protect the religious liberties of struggling bakers and florists who don’t want to sell their services to same-sex spouses. National Review’s editors called it “another skirmish in the endless battle of the Big Gay Wedding Cake.”

The image evoked, of a sole proprietor conscripted unwillingly into labor, is easy to construct, both because it’s the most politically convenient way for conservatives to portray liberals as illiberal, and because it happens to be taken from real life. Some liberals really do want to tell self-employed bakers, photographers, and florists who work from home studios and kitchens that they aren’t free to choose their clients if they use bigoted bases to do so. And that’s allowed conservatives to fashion themselves as tribunes for beleaguered believers, when, more accurately, they’re trying to carve out the legal equivalent of "safe spaces"—much mocked on the right—to shield the right from the emerging marriage equality consensus.

If conservatives merely wanted to protect the occasional “tradition-minded florists and bakers,” as National Review dubbed them, they could have done so explicitly. One could even make a compelling argument that the First Amendment should protect individuals engaged in creative trades who don’t want to be compelled in this way.

But that’s not what they’ve done. Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) doesn’t just establish a defense for sole proprietors who choose to discriminate on the basis of their religious beliefs. It extends such a defense to big employers, too. Indiana has essentially seized on the Supreme Court’s opinion in the Hobby Lobby case, which exempted closely-held corporations from the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that employer sponsored insurance cover contraception, and used it to fashion a law that other employers can use to defend themselves in discrimination suits.

The question isn’t: Should a sole proprietor be free to tailor her business to her religious beliefs? It's: Should the kind of exemption that might make sense for an individual baker or photographer or florist apply to large places of employment? Should businesses like Hobby Lobby, which has more than 600 stores in America, be allowed to sell goods and services that gays and lesbians aren’t allowed to purchase?

Indiana’s RFRA suggests they should at least be able to argue as much in court. As the backlash to the law suggests, a combination of market forces and cultural pressures will probably prevent most entrepreneurs who oppose gay marriage from turning their views into business practice. And if they tried, they might very well lose in court.

But even if Indiana’s RFRA ultimately carries few practical consequences, it’s still a worthy target, and Indiana Republicans deserve all the grief they’re getting.

As a purely logistical matter, Indiana’s RFRA stacks the deck for discriminatory businesses. Same-sex couples denied hotel rooms, or meals, or even wedding venues could theoretically sue, and many probably would. Where protected by non-discrimination laws, some might even win. But the effect in the moment, when the gay customer seeks to pay for a service, would be the same as if the discrimination had been state-sanctioned: They customer would have to find other accommodations.

Governments shouldn’t strive for neutrality on this point, let alone nominal neutrality—even if religious carveouts like Indiana’s RFRA don’t have the practical effect of inviting extensive discrimination. If the letter and intent of a law creates a large theoretical space for businesses to discriminate, then it's a bad law that deserves the kind of blowback Indiana now faces.

Religious liberty and homey artisans are both sympathetic concepts. And if conservatives were really just concerned with protecting the latter from infringements on the former, they’d win the argument every time. In many cases, they’d be pushing against open doors. But if that’s what they were up to, they wouldn’t be making common cause with the drafters of Indiana’s "religious freedom" law.