Evangelicals are not thrilled about a third coming of Bush. Concerned that former Florida Governor Jeb Bush will receive the GOP nomination thanks to his credit with the party establishment, Evangelical leaders around the country are in talks "to coalesce their support behind a single social-conservative contender," The New York Times’ Trip Gabriel reports. Evangelicals do not believe that Bush “would fight for the issues they care most about: opposing same-sex marriage, holding the line on an immigration overhaul and rolling back abortion rights,” and fear that another bruising round of Republican primaries could lose the GOP the presidential race by failing to unite the party’s base.

Evangelicals have good reason to be worried. Despite Evangelicals' willingness to throw their support behind establishment candidates—they enthusiastically voted for Mitt Romney and John McCain—the United States seems to resemble the Evangelical vision less and less. Since the mobilization of the Christian right as a useful voting bloc back in the 1980s, Evangelicals have enjoyed careful courtship from the Republican establishment, as evident in Senator Ted Cruz’s mating dance with right-wing Christians at his Liberty University announcement speech on Monday. But despite being Republicans’ “biggest, most reliable voting bloc,” in the words of Republican National Committee faith engagement director Chad Connelly, Evangelicals appear to have received relatively little from their arrangement with the GOP.

Next month, the Supreme Court will tackle same sex marriage, and all signs indicate that the justices will legalize same sex marriage nationally. The last bastion of hope for Evangelicals in such a circumstance would be religious freedom legislation like the bill recently signed into law by Indiana Governor Mike Pence, which would allow, inter alia, Christian businesses to refuse service to gay customers. These laws represent a kind of retreat from calls for gay-marriage bans, a shield of isolation around small enclaves of Evangelical sentiment that were ultimately incapable of winning the larger political fight. Likewise, despite the willingness of GOP candidates to speak to Evangelical concerns about abortion—29 percent of Evangelicals consider it a "critical issue" for our country—Roe v. Wade has not been overturned, and abortion is not illegal in a single American state. Instead, states have taken to fiddling with regulations relating to waiting periods, counseling, invasive ultrasounds, and parental notification in order to construct makeshift de-facto bans. Pornography, despite the best efforts of Evangelicals over several decades, is not banned. Evolution, too, persists in public schools, along with sex-ed; indeed, the only broadly Evangelical-backed political project that seems to have a prayer at the moment is comprehensive immigration reform, the success of which will largely depend upon keeping people like Ted Cruz out of office.

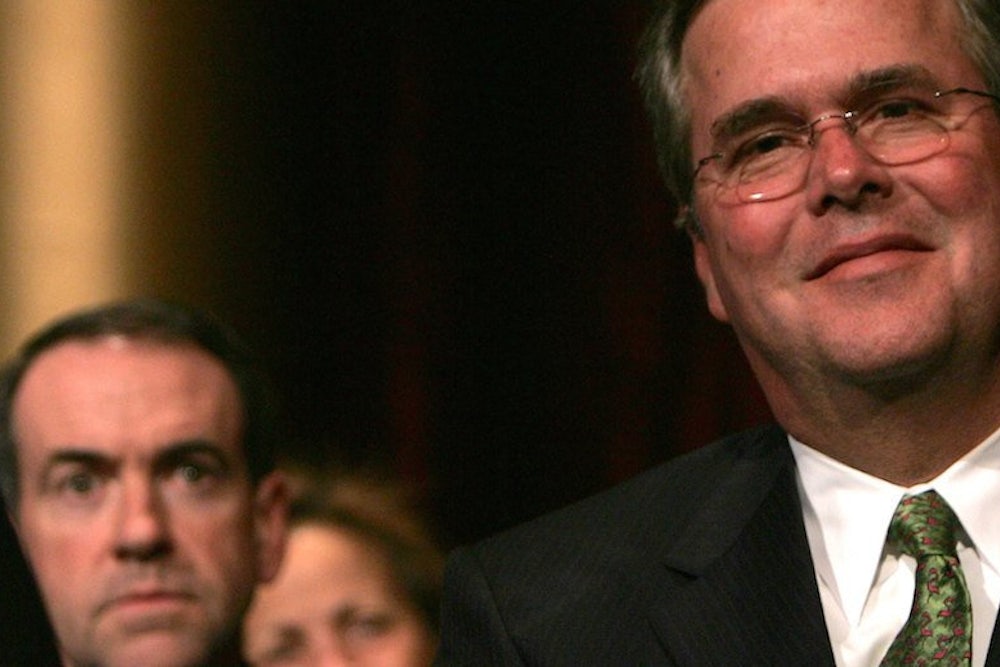

Some Republicans, like former Fox News host Mike Huckabee, are upfront about the fact that Evangelicals have been taken for a ride by the GOP. “They’re treated like a cheap date,” Huckabee told Politico during a 2013 interview, “always good for the last-minute prom date, never good enough to marry.” Evangelicals are always game to hit the polls, in other words, when the GOP needs to pull out a win: but that doesn’t necessarily mean Republicans will be invested in pushing Evangelical issues once they get into office, or that they'd have any success if they tried.

Faced with the inability of their alliance with the Republican Party to produce much more than militarism and deregulation, neither of specific moral interest to Evangelicals, the Evangelical polity itself has begun to split, with some clinging to the triumphalist rhetoric of the past, in which America was a Christian nation and Christianity was an American religion, while others have moved on to lobbying for cells of legal protection from the country’s rapidly shifting moral landscape. For this reason, Religion Dispatches’ Sarah Posner notes, most Evangelicals would “rather hear the candidates talk about religious freedom, not offer overwrought displays of piety blended with patriotism.”

If Jeb Bush is interested in capturing the Evangelical vote, he could promise to push for laws that protect religiously motivated employers from legal censure should they choose to refuse business to LGBT clients. The fact that these laws have been a struggle even at the state level (Arizona governor Jan Brewer, no fan of same sex marriage, still vetoed such a measure last February, while Utah’s Republican-controlled legislature settled on a compromise earlier this month) suggests that they would be even more of a headache at the national level. But if history has revealed anything about the relationship between Evangelicals and their Republican allies, it’s that the promises made and positions telegraphed during campaigns don’t have to be kept.

Still, it seems that the rift between establishment Republicans and Evangelicals will be injurious to the GOP in the long term. As time passes, leveraging the necessary political force to reverse many of the decisions that most rankle the Christian right, including Roe and same-sex marriage, will become even more challenging, making it less likely that an Evangelical favorite could do much to roll these policies back even if elected. And, as failures on that front continue, Evangelicals will likely keep seeking out alternative candidates to rally around, further fracturing a GOP base already tugged in strange directions by the Tea Party. Any Evangelical darling (Huckabee, for example) would likely turn out unelectable in a national election, meaning that Evangelical success will add up to an easy win for Democrats, and another round of disappointments for the Evangelicals themselves. In short, the romantic alliance that was sold to Evangelicals when the Moral Majority helped deliver Ronald Reagan to the White House appears finally to have unraveled altogether.

Which ultimately might be an improvement for Christian politics. As Kevin Kruse notes in his forthcoming book One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America, the alliance between Christian voters and politicians on the right was largely a calculated product born of plush industrialist funding and the handy rhetoric of the McCarthy era. But with the threat of Soviet aggression dissolved and the political promise of the Republican-Evangelical coalition played out, perhaps Evangelicals will be able to look beyond a frustrating alliance in which their interests were always low priority. The faith and family left, as the Pew Foundation has termed it, awaits their support.