Judith Shulevitz’s contemplative March 21 New York Times essay on the purported over-sensitivity of college undergraduates provoked paroxysms of anxiety among the commentariat, eliciting responses from Slate to The Washington Post and beyond.

Among other collegiate eccentricities, Shulevitz details the somewhat infantile soothing materials set aside in a private room for Brown University students who felt upset by discussions of sexual assault. The walls of this room took on a near apocalyptic metaphorical significance for the chattering class, with the Foundation For Individual Rights in Education worrying that “universities cannot fulfill their vital function as places where students learn how to think, research, and debate if community members strive to avoid speech that makes them uncomfortable.” At the National Review Online, Charles C. W. Cooke adduced the Brown safe space as an apparatus of a new McCarthyism, while Reason’s Robby Soave declared that such accommodation “emboldens [undergraduates] to seek increasingly absurd and infantilizing restrictions on themselves and each other.”

All this coincided with an incident at Reed College in which an undergraduate was asked not to attend discussion sections of a required humanities course after he repeatedly made remarks about rape and feminism that the course instructor deemed disruptive. Conservative outlets took up the cause, convinced that the student’s non-PC perspective was responsible for his censure. As Mary Emily O’Hara pointed out at The Daily Beast, the misguided undergraduate swiftly became a stand-in for all of the conservative angst about political correctness and constitutional issues that would normally fester.

After their standard-bearer penned a 16-page manifesto declaring himself a God and contemplating his martyrdom, conservatives might be reconsidering. Like many college kids, the student at the center of this tempest in a #tcot appears to be more troubled than principled—or, more charitably, extremely immature.

The fact that college students are, in many cases, caught in the throes of a turbulent maturation is precisely why using their campus customs as political rallying points is a bizarre move. College kids are immersed in a peculiar atmosphere that is not replicable outside campus grounds; never again will a person find herself both adult and child, learning to navigate life on her own while still deferring to parental assistance and adult guidance. Nor will she find herself in a flock of people narrowed into streams of special interests by concentration or major. The political cultures of college are remarkably different from those that develop elsewhere; this is especially true of the elite colleges that the media tends to focus on.

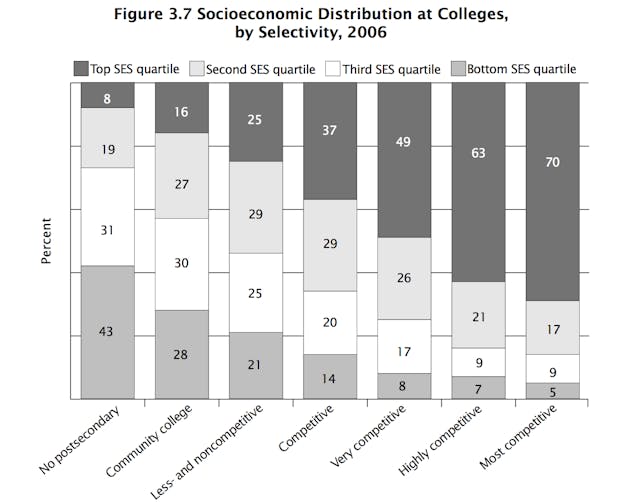

Though the media class may host an unusually high concentration of elite college graduates, the most selective schools are still very removed from the nation as a whole. Students at elite colleges differ markedly from those at less selective schools, and differ even more from those who do not pursue post-secondary education. Far from forming a representative sample of the population at large, students at highly selective schools are overwhelmingly from the upper echelons of society, with a relatively scant representation of students from lower socio-economic status families.

Which is not to say that the political pursuits of undergraduates at elite institutions are inherently ridiculous, but only that they are probably not representative of national trends in any serious way. Comfy hideouts for unsettled undergraduates might rankle those with a vested interest in opposing a particular brand of feminist politics, but drawing the line at internal safe spaces is a strange decision when elite colleges themselves are generally insulated from the politics of the United States. Universities are their own padded rooms, and despairing because they contain smaller cells of consensus is a waste of time.

There are, of course, intersections between university politics and the outside world: As Purdue instructor Freddie deBoer points out, much of the reason university staff feel so compelled to comply with student demands for sensitivity has to do with our weak national safety net and the gradual destruction of labor unions. To really underwrite an environment of robust debate, deBoer concludes, would require that all parties be ensured some measure of security regardless of the fallout—a circumstance right-wing politics would be loath to promote. But doing so would at least represent a sensible application of national politics to campus culture.

Getting angry at kids who leave lectures on rape is as useless as it is politically incoherent: What is the proper response to students who wish to exit voluntary lectures and go someplace else? Should they be forced to stay? How would we ensure that they are actually listening?

For students still developing their politics and personal strategies for grappling with views they find disagreeable, there isn’t much harm in stepping out of a lecture hall and into a safer space. Given that safe spaces have been a part of feminist discourse since the early days of the women’s movement, it seems unlikely that they will suddenly proliferate through broader culture, robbing us all of fair discourse.

A far likelier scenario is that colleges will—and should!—remain loci of experimental politics and their expressions, and that elite institutions will remain culturally removed from the world around them by nature of their constituents and the shape of the academic labor market. A continued obsession with campus culture will surely remain a politically impotent habit among the media class—unless those with axes to grind take up the cause of university staff as tenuous employees and citizens of a weak welfare state, a possibility even more distant than campus cultures suddenly mattering to the world at large.