House and Senate Republicans working on their respective budgets this week face the same problem. How to draft a budget resolution that placates defense hawks, who want more money for defense spending, as well as deficit hawks, who want to keep spending under the caps set by the Budget Control Act? Those two camps may be able to compromise—and since budget resolutions cannot be filibustered, Democrats have little role in this process.

Eventually, Republican appropriators will have to turn those budget resolutions into government funding bills. Those bills can be filibustered. Republicans thus have to find a compromise between defense and deficit hawks that fulfills Democrats’ demand that any increase in defense spending is accompanied by a corresponding increase in nondefense spending. That needle is impossible to thread. Eventually, one of those groups is going to lose—and a brief moment in a Senate Budget Committee hearing last offered a strong hint at who that loser will be.

For now, Republicans are looking for middle ground among themselves. That’s important because if they can’t agree—meaning each house passes a budget and resolves the differences in a conference committee—they can’t pass special instructions to respective committees to make other tax and spending changes, most notably repealing the Affordable Care Act. That gives the GOP a huge incentive to find a way to pass a budget resolution in each chamber.

In the House, the Republican leadership is using an obscure parliamentary procedure to allow the conference to vote on two budgets, one with increased defense spending and one without it. The one that receives more votes will be the House GOP’s budget.

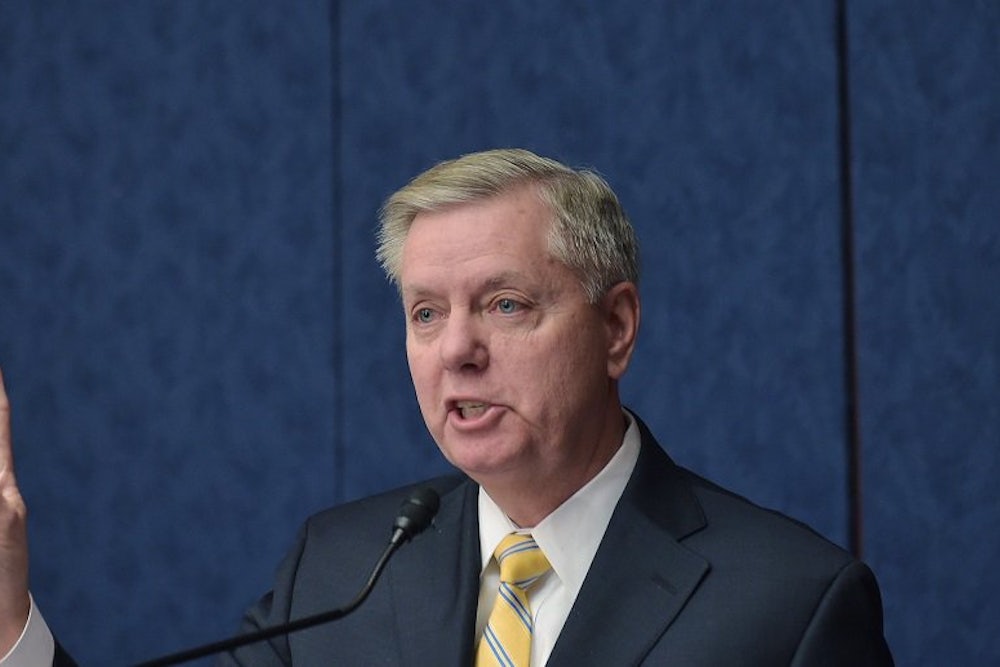

In the Senate, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell finds himself in a worse position. Because Republicans control just 54 seats, losing just four votes means the budget won’t pass. To placate defense hawks like Senators Lindsey Graham and Kelly Ayotte, the Senate Budget Committee passed an amendment last week that would use a budget gimmick to effectively increase defense spending outside of the spending caps. That budget gimmick is a separate fund called Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), which is specifically alloted for overseas military operations. But money is fungible, allowing the Department of Defense to use it for many different purposes. The amendment increased OCO funding from $58 billion in 2016 to $96 billion. Officially, defense spending remains steady at $521 billion.

But the additional OCO money is subject to a 60-vote threshold. Democrats can—and will—block it. In a way, this isn’t a big deal. Democrats would eventually be able to filibuster the defense appropriations bill anyway. “A budget process is one where every member gets to weigh in, and this was important to some members,” Ayotte told Politico. “So we get to the point where we mark up the appropriations bill, we’re going to need 60 votes regardless, but it’s very important that we got the OCO money in terms of increased spending for defense that’s needed given the threats we face around the world.” The OCO budget gimmick was just a stopgap measure to find middle ground between Republican deficit and defense hawks. The real problem of overcoming a Democratic filibuster always remained.

During that Senate Budget Committee hearing last week, an amendment offered by Senator Patty Murray offered a glimpse into how this fight will eventually end. Murray’s amendment would have raised the defense and nondefense spending caps for the 2016 fiscal year by $37 billion each. She would offset it by using the Congressional Budget Office’s most recent budget estimates. How does that actually pay for the increased spending? The Senate GOP’s budget used CBO’s revenue estimates for the next 10 years. The budget office’s most recent report, released in March, raised those estimates by $77 billion—slightly more than needed to offset the increased spending.

Let’s be clear: This is basically a gimmick. As Senate Budget Committee Chairman Mike Enzi said right before the committee members voted on the amendment, the Senate will adopt the new baseline anyway. Doing so will decrease the budget’s 10-year deficit by $74 billion. Murray is just trying to take advantage of the fact that Enzi did not incorporate CBO's new estimates into this budget. In other words, she's not raising additional money through new taxes or saving money through spending cuts. She's just asking to increase spending while using a different baseline—and Republican deficit hawks have no interest in increasing spending, even if the deficit remains the same.

Budget gimmicks get a bad name in Washington. Sometimes, they are the necessary grease to pass legislation and solve crises. In this case, Murray’s amendment is rather elegant. It would increase both nondefense spending and defense spending by equal amounts, satisfying Democrats and Republican defense hawks. At the same time, the 10-year deficit would be unchanged, without any new taxes.

Murray’s amendment failed by a 12-10 party line vote. But not before, Senator Lindsey Graham almost voted for it. When it came time to vote, he said he was an “uncertain no" (around 1:05 mark):

That statement is a sneak preview of things to come. It reveals that Graham—and, in all likelihood, other defense hawks—are more concerned with increasing defense spending than with keeping nondefense spending under the spending caps. Therein lies the outcome of this budget fight: a deal that raises defense and nondefense spending—and cuts out Republican deficit hawks.

The process is going to get messy. Republicans will have to placate the right-wingers furious at increasing nondefense spending. But we also have a recent example of such a deal: The budget Murray and Representative Paul Ryan crafted at the end of 2013, which raised the spending caps for the 2014 and 2015 fiscal years. Deficit hawks in the GOP were furious then, but ultimately lacked the power to kill the deal. Expect more of the same during the coming months.

Update: This piece originally said that the budget won't pass the Senate if McConnell loses five votes. He almost certainly can't lose four votes. Vice President Joe Biden would cast the tie breaking vote in that scenario.