Judith Shulevitz’s New York Times op-ed on Sunday about colleges and “safe spaces” paints a bleak picture of campus life in America today. Titled “In College and Hiding From Scary Ideas,” her piece contains example upon example of students aghast at the possibility that their schools would force or even allow them to confront controversial ideas—and describes a safe space at Brown as a “room was equipped with cookies, coloring books, bubbles, Play-Doh, calming music, pillows, blankets and a video of frolicking puppies.”

“Safe spaces,” writes Shulevitz, “are an expression of the conviction, increasingly prevalent among college students, that their schools should keep them from being ‘bombarded’ by discomfiting or distressing viewpoints. Think of the safe space as the live-action version of the better-known trigger warning.”

Certain things happening at colleges today are indeed silly, if not downright destructive. But before joining the chorus of those tsk-tsking today’s privileged youth for their hypersensitivity, we should ask whether such extreme cases are the norm or the exception. Conservative critics of academia have long pointed to the most scandalous-sounding or jargon-filled workshop titles as evidence that higher ed is in shambles, ignoring the Shakespeare courses and other signs that students are learning more or less what they always had been. While Shulevitz deserves credit for pointing to several specific examples of campus absurdities, we don’t really get a sense of the scope. Nor is it clear whether these are concerns at all colleges, or just at elite colleges. Shulevitz’s anecdotes come from Brown, Columbia, Smith, and others of that ilk. Does this happen at public universities? Community colleges?

The atmosphere I’ve read about, in Shulevitz’ piece and the many articles about trigger warnings, in no way resembles anything I observed teaching undergraduates over the past several years at New York University. It could be that French-language classes don’t lend themselves to offense, but plenty of French movies do, and I can well remember showing The Mad Adventures of Rabbi Jacob without leading with a trigger warning about the cultural appropriation and slapstick violence that was to come.

College shouldn’t be about making students comfortable, but it also shouldn’t be about making them uncomfortable for discomfort’s sake. The Allan Bloom or Dead Poets Society model of professor-as-provocateur tends to be more about allowing a professor’s ego to express itself than about successfully imparting course-related knowledge.

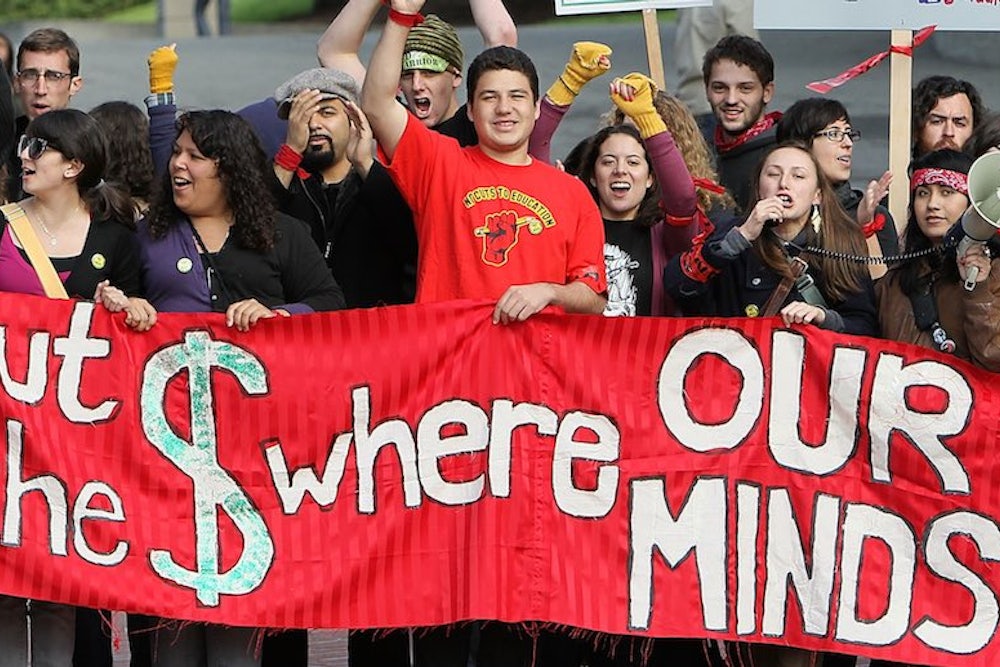

I also wouldn’t be so quick to assume students today are, in fact, hypersensitive. Whether any specific instance of outrage is performative or sincere is something one can only ever speculate (and sometimes, as in the case of Columbia student Emma Sulkowicz’ mattress project, it could be both). Comparing today’s youth with that of her day, Shulevitz writes, “I’m old enough to remember a time when college students objected to providing a platform to certain speakers because they were deemed politically unacceptable. Now students worry whether acts of speech or pieces of writing may put them in emotional peril.” Shulevitz wouldn’t need to be especially old to remember this—students have been protesting commencement speakers for the past several years.

Finally, we should emphasize the role colleges themselves play in promising safe spaces, and not attribute this shift, if it’s indeed a real one, to some sort of ambient entitlement among today’s oh-so-fragile youth. Shulevitz blames the students themselves, and only briefly alludes to colleges’ own contribution, framing it as a capitulation to student demand: “Now students’ needs are anticipated by a small army of service professionals—mental health counselors, student-life deans and the like."

But the notion of the campus itself as a safe space is hardly one that students invented. From even before they matriculate, students learn that college is a special place. Holistic admissions gives students the impression that every member of the campus community has been hand-selected for his or her character, so whenever one student offends (or assaults) another, it comes as that much more of a shock. Campus security forces reinforce the notion that university students are this important class of person deserving of extra safety. Growing up, I was struck that New York children like me would take public transportation alone to school, while NYU’s nominally adult students were provided shuttles. Such factors combine to give students who may have been plenty resilient in high school the impression that they’re now having their every concern looked after. Needing to distinguish themselves from one another, and—as Michael B. Dougherty points out—to justify the expense, elite colleges keep ramping up amenities. What they're selling, then, is the campus as a world apart.

The centrality of college costs to these debates cannot be overstated. Slate’s Amanda Hess addressed this in her analysis last year of the commencement-speaker controversies:

These recent flare-ups reveal less about the speakers than the students’ own entitlement—students who believe they have paid for the right to a commencement experience that perfectly reflects both the stature and the political values of their elite higher educations. They want their commencements to be both high in profile and rich in personal meaning. That’s not just political correctness gone awry; that’s a bunch of 22-year-olds thinking they are owed exactly the experience they want. On the other hand: A uniquely tailored experience is just what elite schools are promising their students in exchange for their astronomical costs.

This strikes me as almost right, but I’d switch the order. It’s not that students demand that colleges provide a gated-community experience tailored to their every preference. Instead, the elite schools are selling that experience—and given the competitiveness of that marketplace, it’s hardly surprising that campus life sometimes crosses over into the ridiculous. Shulevitz blames the students, and surely they deserve some of it. But they’re demanding exactly the college experience that the brochures have promised them.