Wikipedia is the anonymous source no journalist can quote. There are many reasons for that, but chief among them is the most obvious: You can never be sure who is doing the writing and editing. People work diligently to ensure the accuracy of the online encyclopedia, and that’s admirable—but still, Wikipedia remains the research equivalent of “For entertainment purposes only.”

Tracking edits made to Wikipedia pages has become a pastime for tens of thousands of Twitter users. Want to know if folks at the U.S. Capitol are padding their Wikipedia resumés? You’re not alone: More than 31,000 people follow @congressedits, an automated Twitter feed that publishes anonymous Wikipedia edits made from Internet Protocol (IP) addresses in Congress. Example: In July 2014, someone using a congressional IP address added a line to the entry on Kansas Representative Tim Huelskamp—not exactly a contender for speaker—deeming him a “national conservative leader.” That bit of re-envisioning went straight online.

Earlier this year, journalist Kelly Weill wondered if anyone at the New York City Police Department (NYPD) was making similar alterations. Weill searched an array of public IP address databases and located approximately 15,000 belonging to the NYPD. Weill and a partner created a computer script that allowed her to pinpoint Wikipedia edits made from computers on the NYPD network. Her investigation, which was published on the website Capital New York on March 13, revealed that significant changes to Wikipedia entries on acts of brutality by the NYPD stemmed from these addresses.

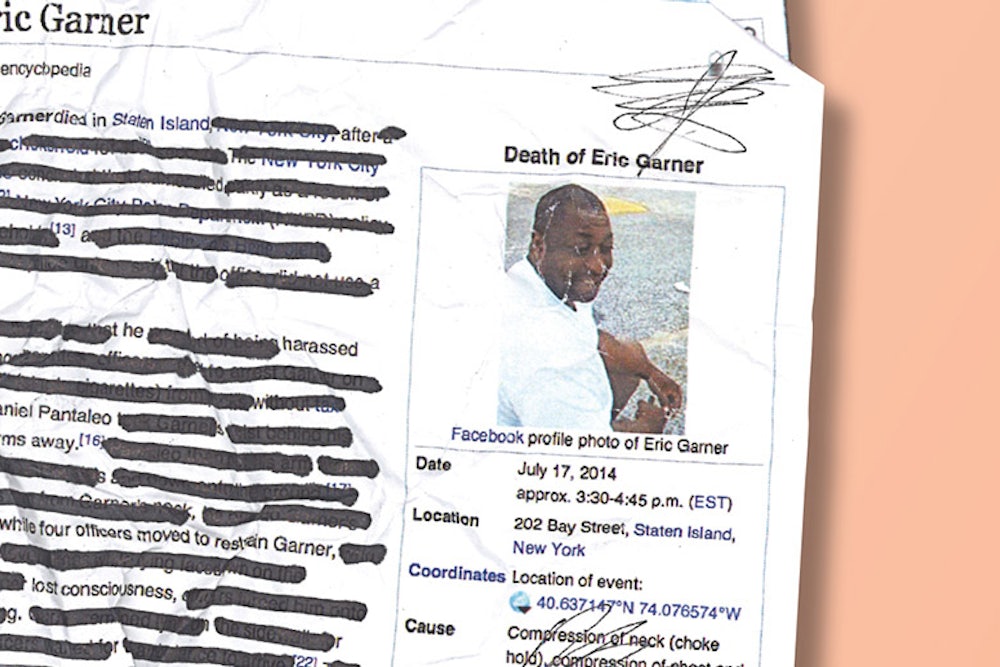

The Wikipedia page on the July choking death of Eric Garner by police officers in Staten Island, which led to widespread protests around the city, was among those altered. The word “chokehold,” for example, was edited twice, augmented once with the modifying phrase “chokehold or headlock,” and on the other occasion deleted and replaced with “respiratory distress.”

The editor also inserted information pointing out that chokeholds were currently legal under New York law. This was correct, and as recently as January, Mayor Bill de Blasio said that he would oppose any effort to outlaw them. What the edit failed to mention was that Use of Force rules outlined in the NYPD Patrol Guide have banned the asphyxiating restraint technique since 1993.

Other revisions shifted blame for Garner’s death from the police to Garner himself. The phrase, “Garner raised both his arms in the air”—a posture of submission—was changed to the potentially hostile, “Garner flailed his arms about as he spoke.” Another sentence observed that “Garner, who was considerably larger than any of the officers, continued to struggle with [police].”

Changes were also made to the page chronicling the death of Amadou Diallo. Diallo, a 22-year-old student and street peddler from Guinea, was killed in 1999 by police officers in the Bronx, shot 19 times as he stood in the doorway of his apartment building. The four officers involved in the killing, who were later acquitted at trial, fired a total of 41 bullets at Diallo, who was unarmed. In one particularly egregious instance, edits made from an NYPD IP address revised the sentence, “Officer Kenneth Boss had been previously involved in an incident where an unarmed man was shot,” to read, “Officer Kenneth Boss had been previously involved in an incident where an armed man was shot.” (Emphasis added.)

Another editor at the NYPD attempted to not just delete words, but an entire entry. One user argued on Wikipedia’s internal “Articles for deletion” site for the removal of the “Sean Bell shooting incident” page. Bell, a 23-year-old living in Queens, was shot and killed by police officers on the night of his bachelor party in 2006. Plainclothes NYPD officers fired on Bell’s car because, they later claimed, another passenger was suspected to have a gun. No weapons were recovered, and three of the five officers on the scene were brought up on charges including manslaughter and reckless endangerment. “[Bell] was in the news for about two months, and now no one except Al Sharpton cares anymore,” the editor wrote. “The police shoot people every day, and [some]times with a lot more than 50 bullets. This incident is more news than notable.” Wikipedia decided not to excise the page.

Editors also revised pages related to the city’s “stop-and-frisk” policy. A citation from Terry v. Ohio, the 1968 Supreme Court case that legitimized the controversial practice under the Fourth Amendment, was added; and this part of the sentence, “... if the circumstances of the stop warrant it, [the officer] conducts a frisk of the person stopped,” was changed to, “... if the officer reasonably suspects he or she is in danger of physical injury, frisks the person stopped for weapons”—implying that “stop-and-frisk” incidents posed a greater threat to police officers than to suspects.

The NYPD has confirmed that at least two officers were involved in the editing—they declined to identify them—but no consequences for the actions are expected. At a March 16 news conference, NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton said that he plans to review the department’s social media policy, which at the time of the edits didn’t include rules for behavior while on Wikipedia. “I don’t anticipate any punishment, to be quite frank with you,” he said.

African Americans have always contended with the erasure of their history, whether in the lessons offered in our schools or in narratives portrayed in the media. The strands connecting African Americans to their origins were severed upon their arrival in this country, and people have inserted agendas into the printed history since slaves were exposed to the Bible.

What Weill detailed in her reporting is a very modern, digital version of that phenomenon. Search for virtually anything these days, and the Wikipedia page will be among the first results, if not the first. Wikipedia’s massive reach means that faulty edits, however minor or seemingly innocuous, alter lived experiences in a meaningful way. Wikipedia may be entertainment, but the actions of the NYPD are entirely serious.

Blair L.M. Kelley, a history professor at North Carolina State University, said that there is always a story that the state wants to tell about itself and its people. Competing with that story is a “hidden transcript”—a concept borrowed from James Scott’s Domination and the Arts of Resistance—that citizens collectively share with each other, but not necessarily with the state.

“When you look at the world, you’ll see a transcript that those in power want you to believe,” said. “But there’s another story. As much as you’re trying to control it, you can’t. There is always another story to tell.”

She suggested that in a bygone era, the NYPD might have simply leaked a positive narrative about a controversial event to a sympathetic journalist. They knew where to go to control the message. Today, though, the picture is more complex, and the state has to work harder to police that hidden transcript. “Power is really a performance,” she said. “It isn’t just something you do; it’s something you perform to look powerful. It appears that the NYPD is trying to perform this narrative of power: What happened was this, this, and this.”

No one knows why officers of the NYPD would take it upon themselves to make alterations to a Wikipedia site—and the police aren’t saying. Perhaps they felt that the articles on the killings of Garner, Diallo, and Bell were inaccurate and needed correction. Or because those live performances of power weren’t enough to steer the story. The truth was ugly and wouldn’t benefit them, and so the folks at One Police Plaza performed their power. It remains to be seen how effective this particular use of force is: The Twitter account @NYPDedits, which uses the same IP address information gathered by Weill, now tracks all Wikipedia changes originating from the NYPD and automatically transmits them online. As of this writing, two additional revisions have been made.

One @NYPDedits tweet, published March 17, corrected punctuation in the entry for John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice. The other, made the same day, involved the page for actor Tyler James Williams, adding a sentence about how the actor’s character on the popular AMC series The Walking Dead was violently killed. Strangely enough, the edit was accurate.

This story was updated to reflect the version that appeared in the May 2015 issue of our magazine.