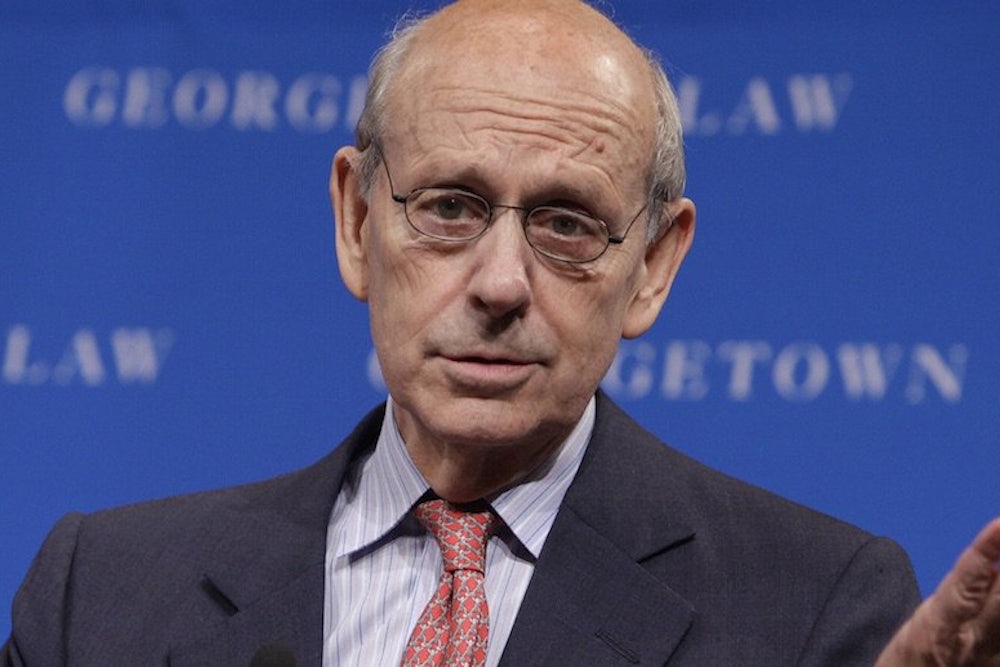

In a wide-ranging chat with Harvard law professor Noah Feldman at 92Y in Manhattan on Thursday, Justice Stephen Breyer got a chance to nerd out about some of his favorite subjects, including government institutions, constitutional structures, and the administrative state. Not exactly the stuff of headlines, but that’s who Breyer is—he’s as much an academic as he is a jurist, a “raging pragmatist,” and a believer in democracy and a progressive view of the Constitution.

But for all his lawyerly, reasoned answers, Breyer stumbled when Feldman asked him about “defining social movements” of this generation—specifically the national discussion surrounding Ferguson and the death of Eric Garner in New York. Do justices care about any of this? His response was a masterful dodge.

“Judges read newspapers, just like everybody else,” Breyer said, and made an oblique reference to his time as a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg in 1964—a time the court was still dealing with remedying segregation in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. He then launched into a procedural lesson on how cases before the Supreme Court are briefed, argued, and decided, making yet another oblique reference—this time to the Rodney King case in the early '90s, when Breyer was an appellate judge in Boston. There, Breyer said, he and his colleagues engaged in the “judicial attitude” of not judging outcomes you are not fully appraised of, no matter the social salience. “That’s a good thing,” he said.

Feldman pushed back and tried to get Breyer to comment on the broader social implications of cases like Ferguson—such as the use of force by police. Still Breyer wouldn’t have it and insisted he could only opine if it came before him “in a particular case.” Yet again, he went on a tangent about history and the New Deal era and how the Supreme Court decided cases then. He finally threw the ball back at Feldman, a Bloomberg View columnist, saying, “That’s your job, to write about how the great social movements influence the judges. Maybe they do.”

And that was that. Breyer, the great progressivist, has no comment about Ferguson. He’s had something to say or do in a number of key generational moments—Watergate, the drug war, Bush v. Gore, the post-9/11 years—and has worked for all three branches advancing democratic solutions. And yet the subject of Ferguson, which is not a pending matter before the Supreme Court, cannot get a passing mention.

Breyer’s punt must have been a letdown for Feldman, who as a law professor surely has had students who are grappling with the questions Ferguson raises. But it’s also a loss for everyone else, who will now be deprived of hearing an important legal mind speak to these issues. Breyer is an intellectual on the court—he’s known for his lengthy hypotheticals at oral arguments, his painstakingly reasoned opinions, his fanciful dissents annexed with appendices filled with charts and social-science research. The man has views. So what does he think of grand juries generally? About the court’s own precedents on the use of force? About stop-and-frisk, which the court invented? About judge-created rules to protect police officers from liability? About the myriad exceptions and good-faith passes the Supreme Court has given to police with respect to the Fourth Amendment? There’s no way to know.

Had Breyer indulged the Ferguson question, perhaps Feldman might have followed up with an inquiry on other civil-rights barriers erected by the court, as in voting rights and affirmative action. On this latter subject, in particular, Breyer breaks with his liberal colleagues and believes states can eliminate it by way of the democratic process. Some thoughts on how minorities will ever prevail under that test, or if they’re meant to prevail at all, would have been instructive.

Or perhaps the conversation might have veered into Breyer’s biggest criminal justice legacy: His role as an architect of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, promulgated nearly 30 years ago to bring order and consistency to federal sentencing. Breyer might have shared about some of his regrets with the guidelines, and how over the years they led to a sentencing regime that tied the hands of judges and punished blacks and Latinos more harshly than anyone else in the federal system. That could’ve dovetailed into a discussion about United States v. Booker, which 10 years ago rendered the sentencing guidelines advisory—and ostensibly freed judges to use discretion—but whose effects have been questionable with respect to unduly punitive sentences.

These are weighty subjects, and perhaps 92Y wasn’t the right forum for them. But will there ever be a right forum? Without the benefit of a case or controversy before the Supreme Court, it’s clear Breyer will never get to talk about Ferguson or the many things it stands for. Let others write about the great social movements. That’s none of his business.