Fashion writing is a funny business. Nestled next to lavish ads, it can’t easily say what it really thinks. “Ugly” becomes “conceptual”; “looks like grandma’s nightie” becomes “a return to old-fashioned femininity.” The fashion writer and scholar Anne Hollander—who pinpointed some of these empty niceties in a 1997 column for Slate—was not among the panderers. In her pieces for The New Republic and in her groundbreaking book Seeing Through Clothes, she presented clothing as it really is: art, armor, frippery, fantasy. Here, she playfully chronicles the 1960s and 1970s revolution that brought turtlenecks, bell-bottoms, and wide ties into men’s wardrobes. “There is no tradition of clothes criticism that includes serious analysis,” she once complained. But she wrote exactly that.

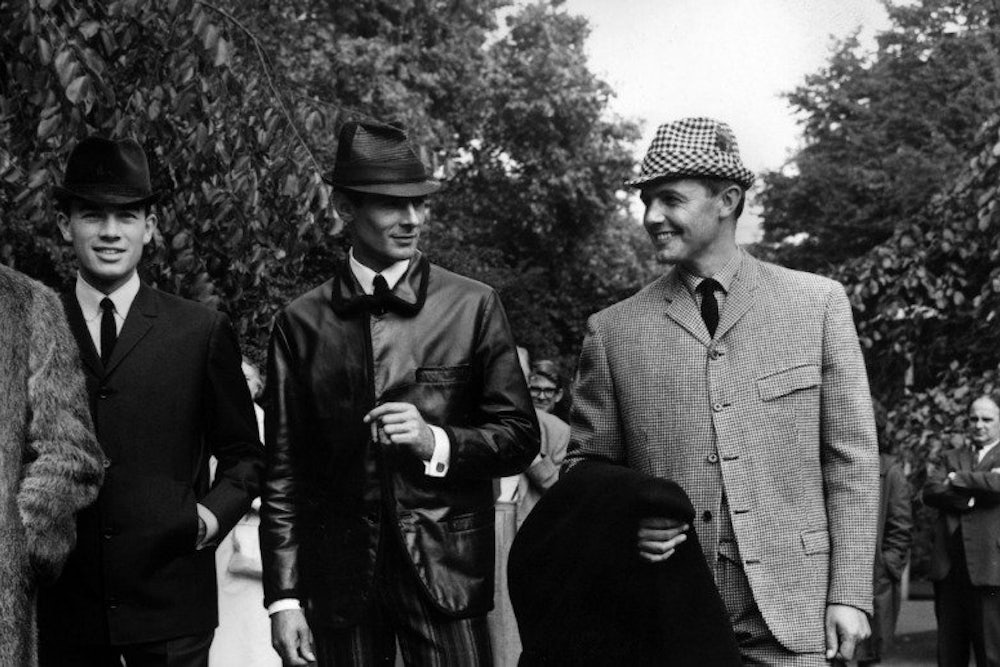

The last decade has made a large number of men more uneasy about what to wear than they might ever have believed possible. The idea that one might agonize over whether to grow sideburns (sideburns!) or wear trousers of a radically different shape had never occurred to a whole generation. Before the mid-sixties whether to wear a tie was about the most dramatic sartorial problem: Everything else was a subtle matter of surface variation. Women have been so accustomed to dealing with extreme fashion for so long that they automatically brace themselves for whatever is coming next, including their own willingness to resist or conform and all the probable masculine responses. Men in modern times have only lately felt any pressure to pay that kind of attention. All the delicate shades of significance expressed by the small range of possible alternatives used to be absorbing enough: Double- or single-breasted cut? Sports jacket and slacks or a suit? Shoes with plain or wing tip? The choices men had had to make never looked very momentous to a feminine eye accustomed to a huge range of personally acceptable possibilities, but they always had an absolute and enormous meaning in the world of men, an identifying stamp usually incomprehensible to female judgment. A hat with a tiny bit of nearly invisible feather was separated as by an ocean from a hat with none, and white-on-white shirts, almost imperceptibly complex in weave, were totally shunned by those men who favored white oxford-cloth shirts. Women might remain mystified by the ferocity with which men felt and supported these tiny differences, and perhaps they might pity such narrow sartorial vision attaching so much importance to half an inch of padding in the shoulders or an inch of trouser cuff.

But men knew how lucky they were. It was never very hard to dress the part of oneself. Even imaginative wives and mothers could eventually be trained to reject all seductive but incorrect choices with respect to tie fabric and collar shape that might connote the wrong flavor of spiritual outlook, the wrong level of education or the wrong sort of male bonding. It was a well ordered world, the double standard flourished without hindrance, and no man who stuck to the rules ever needed to suspect that he might look ridiculous.

Into this stable system the width-of-tie question erupted in the early sixties. Suddenly, and for the first time in centuries, the rate of change in masculine fashion accelerated with disconcerting violence, throwing a new light on all the steady old arrangements. Women looked on with secret satisfaction, as it became obvious that during the next few years men might think they could resist the changes, but they would find it impossible to ignore them. In fact to the discomfiture of many, the very look of having ignored the changes suddenly became a distinct and highly conspicuous way of dressing, and everyone ran for cover. Paying no attention whatever to nipped-in waistlines, vivid turtlenecks, long hair with sideburns and bell-bottom trousers could not guarantee any comfy anonymity, but rather stamped one as a convinced follower of the old order—thus adding three or four dangerous new meanings to all the formerly reliable signals. A look in the mirror suddenly revealed man to himself wearing his obvious chains and shackles, hopelessly unliberated.

Now that fashion is loose upon the whole male sex, many men are having to discard an old look for a new, if only to maintain the desired distance from the avant-garde, as women have always known how to do. Just after the first few spurts of creative masculine dress in the mid-sixties, like the Beatle haircut and the wide ties, daring young women began to appear in the miniskirt, and men were temporarily safe from scrutiny as those thousands of thighs came into view. The other truly momentous fashion phenomenon to arise at the same moment, the counterculture costume, established itself absolutely but almost unnoticeably among both sexes while all eyes were glued to those rising hems. In fact miniskirts were the last spectacular and successful sexist thunderbolt to be hurled by modem women, before the liberation movement began to conspire with the nature movement to prevent semi-nudity from being erotic (hot pants, rightly short lived, were too much like science fiction). Men who might have longed in adolescence for the sight of unconfined breasts were perhaps slightly disconcerted when breasts at last appeared, bouncing and swaying on the public streets in the late sixties, since they were often quite repellently presented to the accompaniment of costumes and facial expressions somehow calculated to quell the merest stirring of a lustful thought. But that was only at the beginning, of course. Since then the visible nipple has become delightfully effective under proper management.

Following bare legs, free breasts and the perverse affectation of poverty, dress suddenly became a hilarious parlor game, and men were playing too. Chains, zippers, nailheads and shiny leather were available in any sort of combination. Extremely limp, tired and stained old clothes could also be tastefully festooned on anybody who preferred those. Universal ethnic and gypsy effects, featuring extraordinary fringes and jewelry worn in unusual places, vied with general romantic and menace effects, featuring dark glasses, sinister hats and occasional black capes. In addition all the parts were interchangeable. Both sexes participated, but then finally many people got tired and felt foolish and gave it up. Men, however, had had a taste of what it could be like, and all the extreme possibilities still echoed long after the extreme practices had subsided, even in the consciousness of those who had observed and never tried to join.

During the whole trend men floundered, and still do, longing for the familiar feel of solid ground. Hoping to appease the unleashed tide with one decisive gesture, many men bought a turtleneck dress shirt and wore it uncomfortably but hopefully with a medallion on a chain, only to discover within three months that it would not do. Many a conservative minded but imaginative fellow, eager to avoid new possibilities for feeling foolish and to look at least attuned to the modem world, had expensive tailoring done in a bold and becoming new shape, hoping to stay exactly like that for the rest of his life, or at least for a few more years. He then discovered himself still handsome but hopelessly dated in a season or two. Mustaches sprouted and hastily vanished again, sidebums were cultivated and sometimes proved to grow in upsettingly silver gray. Hair, once carefully prevented from exhibiting wayward traits, was given its head. Men balding on top could daringly relish luxuriant growth around the sides, and the Allen Ginsberg phenomenon frequently occurred: a man once cleanshaven and well furred on top would compensate for a thinning poll by growing a lengthy fringe around its edges and often adding an enormous beard. The result was a sort of curious air of premature wisdom, evoking mental images of the young Walt Whitman spiced with swami. Other, more demanding solutions to the problem of thinning hair among those wishing to join the thick thatch with sideburns group required an elaborate styling of the remaining sparse growth, complete with teasing and spray and a consequent new dependence, quite equal to anything women submit to, upon the hairdressing skill of the professional, the family or the self.

Early in the game, of course, long hair for men had been just another badge. Most men had felt quite safe from any temptation to resemble those youthful and troublesome citizens who were always getting into the newspapers and the jails. Some young people, eager to maintain a low profile, had also found the hairy and ragged look an excellent disguise for masking a serious interest in studying the violin or any similar sort of heterodox concem. During all this time no one ever bothered girls about the length of their hair, or found any opportunity to throw them out of school for wearing crew cuts for instance. Even if half-inch fuzz had been the revolutionary mode for girls, they would have undoubtedly been exempt from official hassling, except possibly by their mothers. But, as it happened, the gradually evolved migrant worker, bowery bum costume worn by the armies of the young required long hair for both sexes. The very similarity of coiffure helped, paradoxically, to emphasize the difference of sex. After a while the potent influence of this important sub fashion that was at first so easy to ridicule came steadily to bear on the general public's clothes-consciousness. The hairy heads and worn blue denim legs all got easier to take, and indeed they looked rather attractive on many of them. People became quite accustomed to having their children look as if they belonged to a foreign tribe, possibly hostile; after all under the hair it was still Tom and Kathy.

In general, men of all ages turn out not to want to give up the habit of fixing on a suitable self-image and then carefully tending it, instead of taking up all the new options. It seems too much of a strain to dress for all that complex multiple role-playing, like women. The creative use of male plumage for sexual display, after all, has had a very thin time for centuries: the whole habit became the special prerogative of certain clearly defined groups, ever since the overriding purpose of male dress had been established as that of precise identification. No stepping over the boundaries was thinkable—ruffled evening shirts were for them, not me; and the fear of the wrong associations was the strongest male emotion about clothes, not the smallest part being fear of association with the wrong sex.

The difference between men's and women's clothes used to be an easy matter from every point of view, all the more so when the same tailors made both. When long ago all elegant people wore brightly colored satin, lace and curls, nobody had any trouble sorting out the sexes or worrying whether certain small elements were sexually appropriate. So universal was the skirted female shape and the bifurcated male one that a woman in men's clothes was completely disguised (see the history of English drama), and long hair or gaudy trimmings were never the issue. It was the nineteenth century, which produced the look of the different sexes coming from different planets, that lasted such a very long time. It also gave men official exemption from fashion risk, and official sanction to laugh at women for perpetually incurring it.

Women apparently love the risk of course, and ignore the laughter. Men secretly hate it and dread the very possibility of a smile. Most of them find it impossible to leap backward across the traditional centuries into a comfortable renaissance zest for these dangers, since life is hard enough now an)rway. Moreover along with fashion came the pitiless exposure of masculine narcissism and vanity, so long submerged and undiscussed. Men had lost the habit of having their concern with personal appearance show as blatantly as women's —the great dandies provided no continuing tradition, except perhaps among urban blacks. Men formerly free from doubt wore their new finery with colossal self-consciousness, staring covertly at everyone else to find out what the score really was about all this stuff. Soon enough the identifying compartments regrouped fhemselves to include the new material. High heels and platform soles, once worn by the Sun King and other cultivated gentlemen of the past, have been appropriated only by those willing to change not only their heights but their way of walking. They have been ruled out, along with the waist-length shirt opening that exposes trinkets nestling against the chest hair, by men who nevertheless find themselves willing to wear long hair and fur coats and carry handbags. Skirts, I need not add, never caught on.

What of women during the rest of this revolutionary decade? The furor over the miniskirt now seems quaint, like all furors about fashion, and the usual modifications have occurred in everybody's eyesight to make them seem quite ordinary. Trousers have a longer and more interesting history. Women only very recently leamed that pants are sexy when fitted tightly over the female pelvis. When trousers were first worn by women, they were supposed to be another disturbingly attractive masculine affectation, perfectly exemplified by Marlene Dietrich doing her white tie and tails number in Morocco. They were also supposed to be suitable for very slim, rangy outdoor types low on sex appeal. Jokes used to fly about huge female behinds looking dreadful in pants, and those who habitually wore them had to speak loudly about their comfort and practicality. Gradually, however, it became obvious that pants look sensational, not in the least masculine, and the tighter the better. Long trousers, along with lots of hair, breasts and bareness, became sexy in their own right. Everybody promptly forgot all about how comfortable and practical they were supposed to be, since who cared when they obviously simply looked marvelous. They are in fact a great bore on slushy pavements and very hot in summer but nobody minds. Nevertheless the extremely ancient prejudice against women in trousers lingered for a very long time. Many schools forbade pants for girls even though they might wear their hair as they liked, and the same restaurants that required the male necktie prohibited the female trouser. Even in quite recent times pants still seemed to connote either excessively crude informality or slightly perverted, raunchy sex. The last decade has seen the end of all this, since those sleek housewives in TV ads who used to wear shirtdresses all wear pants now, and dignified elderly ladies at all economic levels wear them too, with crystal earrings and nice, neat handbags. After all these anxious and newsworthy borrowings, all the classes and the sexes remain as distinguishable as ever.