On Thursday, a slew of American Catholic publications, including America Magazine, National Catholic Register, National Catholic Reporter, Our Sunday Visitor, and Patheos Catholic announced their joint commitment to abolishing the death penalty in the United States. Prompted by an upcoming Supreme Court hearing on the use of certain drug combinations in lethal injections, the statement represents a rare and welcome moment of unity among Catholics of varied political commitments. No such unity can be found among the 78.2 million American Catholics themselves, and that's because one group opposes these publications' position on the death penalty: white Catholics.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church holds that if non-lethal methods are sufficient for preventing a criminal from doing further harm, then those methods should be preferred over lethal punishment. It isn’t difficult to imagine why: The Catholic Church values a consistent respect for human life, the kind of approach Chicago Cardinal Joseph Bernadin called “a seamless garment”—that a person’s guilt or innocence is irrelevant to the inherent value of their life. That's why the Church has long opposed capital punishment. Pope John Paul II was an especially eloquent and dedicated advocate for life. Pope Francis, too, has called for the abolition of the death penalty, saying, “It is impossible to imagine that states today cannot make use of another means than capital punishment to defend peoples' lives from an unjust aggressor.”

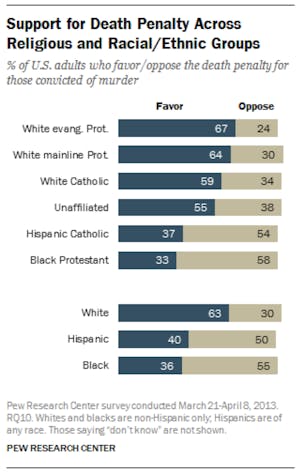

With overwhelming papal consensus and such sound theological reasoning on the Church’s side, one might presume American Catholics are generally united in opposing the use of capital punishment. But that isn’t the case, and a 2014 Pew report found that a significant racial gap divides American Catholics on the subject of capital punishment.

While 59 percent of white Catholics favored the death penalty, only 37 percent of Hispanic Catholics felt the same. Race appears to be a better predictor of one's beliefs about capital punishment than religion is. Why?

The death penalty in America is notoriously racially biased. According to Washington, D.C.’s Death Penalty Information Center, African Americans and Latinos made up 54.4 percent of death row inmates in 2014, though these groups combined make up no more than around 30 percent of the American population as a whole. As David A. Love observed in The Guardian, “given the over-representation of black and Hispanic prisoners on death row, it is hardly surprising that of the 139 capital convicts found innocent since 1973, 61% have been of color.” This alone would be enough to explain why white Catholics seem less troubled than their Hispanic counterparts by the persistence of the death penalty: Capital punishment disproportionately affects communities of color. But it seems facile to presume nothing more than self-interest motivates Hispanic Catholics to adhere to Church teaching when it comes to capital punishment.

Rather, the decision to follow Church teaching on capital punishment despite the American public’s general support for it (Pew notes that 55 percent of the population at large still favors the policy) might be a result of what community exposure to the death penalty reveals about the gap between American political values and Catholic values. Capital punishment opens up a variety of questions, not limited to matters of forgiveness and blame; discrimination and prejudice; the efficacy and accuracy of the justice system; and the authority of the state. In a 2003 paper published in The Journal of Politics, researchers from American University found that “support for capital punishment runs significantly stronger among white people who view individual responsibility as a normative ideal for 'true' Americans,” and that “strong support for the death penalty is much more likely among white people who place a high value on the need for order and deference.” Moreover, the authors noted that “among white Americans, distrust of other people enhances support for capital punishment.”

White Americans, Catholics included, have the privilege of being viewed as "true Americans," an appellation that is evidently accompanied by a variety of other ideological tendencies, including commitment to individual responsibility, a certain lack of cynicism about the functioning of the justice system, and a mistrust of those who don’t fit the supposed American ideal. Yet the facts of the death penalty and its racial bias reveal how flimsy these notions really are. Factors beyond one’s control, like race, often influence the imperfect mechanisms of justice far more than actions do, and the best safeguard against this kind of injustice is to trust one another enough to look past race and ideology and choose instead to value human life. American cultural pathologies can distort the degree to which we all rely on community support to make it through life, but the inequality of capital punishment makes the necessity of community trust and mercy deathly clear.

That aligns with the Church's view, and it's why all American Catholics, white and otherwise, should care about the preservation of human life over the perpetuation of a particular American ideal.