Domesticity, widely understood to have been murdered by Betty Friedan and/or Betty Crocker, has been back on the upswing for a while now. Knitting, backyard chicken-keeping, and the canning of homemade organic rosemary-plum jam are old hat in the country’s more progressive quarters. A slew of books like The Hip Girl’s Guide to Homemaking, How to Sew a Button: And Other Nifty Things Your Grandmother Knew and Making It: Radical Home Ec for a Post-Consumer World preach the gospel of domestic self-sufficiency and the value of lost womanly arts.

These domestic manuals tend to rely on a handful of claims. First: Due to technology we’ve lost touch with our innate human need for tactile experiences. Second: Rampant consumerism has driven us to buy what we once made, to our detriment. Third: We can improve our lives, our finances, and the planet by practicing domestic DIY. Though these claims certainly have some merit, they’re often oversold in a grandmotherly, pearl-clutching kind of way. Are Millennials genuinely stymied by their lack of basic sewing skills? Is takeout food really the scourge of the twenty-first century?

Traveling alongside this new domesticity movement is so-called “maker culture,” whose capital is Silicon Valley. Maker culture is about the convergence of technology and DIY artisanry—geeky-cool mad scientists with dreadlocks and DNA tattoos building robot spiders and 3-D printing model trains. It emphasizes informal sharing networks like peer-led online workshops and communal “hackerspaces” complete with welding torches and laser cutters. It’s about taking back the act of production from technology corporations and learning it yourself, soup to nuts.

Maker culture shares many of the concerns of the new domesticity movement. Both see themselves as a reaction to our alienation from the physical world. Both share an anti-corporate spirit. Both are concerned with issues of sustainability. Both share a sometimes over-the-top utopianism. There’s a bit of domesticity in maker culture, and a bit of maker culture in domesticity. Maker Faire, maker culture’s biggest event (think Burning Man minus the designer drugs and nudity), has a section dedicated to domestic-themed projects. And the domestic goddesses of the twenty-first century are usually whizzes at social media, digital photo editing, and online sharing technologies. (If a cupcake goes unblogged, does it taste as sweet?)

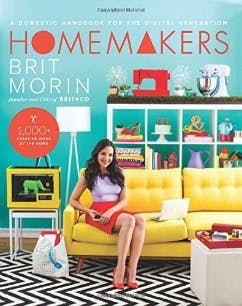

But despite their shared philosophies, the new domesticity movement tends to be largely female-led, while maker culture (like the rest of Silicon Valley) is heavily male. This has been troubled over by participants in both arenas, and slow progress has been made. More men are knitting and canning; maker events are working hard to highlight female makers. Now, a new book, Homemakers: A Domestic Handbook for the Digital Generation, by Brit Morin claims to bridge the two cultures. Being a homemaker is out, Morin says. Being a “home maker” is in. “[T]oday’s generation thrives in the virtual world, but as humans we remain inspired to work and create in the physical world,” Morin writes. “Why can’t these two worlds come together?”

Morin, 29, has fashioned herself as something of a Silicon Valley Martha Stewart. Her company, Brit + Co, is a lifestyle website with a geek-chic bent. In addition to standard women’s magazine fodder like tips on updos and date night makeup, it features DIY craft lessons and articles on female-oriented technologies like fashion apps and wearable tech jewelry. Morin has been featured as a tech and lifestyle consultant on shows like Katie Couric’s “Katie” and the “Today Show.” Just two years after launching Brit + Co in 2011, she scored $6.3 million in funding. Unlike other modern domesticity guides, Morin’s doesn’t fetishize the “natural” and “vintage” and “unplugged.” There’s no renunciation here. Forget sewing your own toilet paper out of old t-shirts or slowing down and smelling the roses. Homemakers is for the woman who really wants it all: a kickass job at Google, a fresh plate of cake pops, and a 3-D printer to make earrings to wear to TechCrunch Disrupt.

The book’s content is an odd hybrid of how-to and futurism. Much of it reads like a guide for recent Stanford grads or aliens who have never been to earth: instructions on boiling eggs and cutting onions, illustrated lists of what one needs to furnish a living room (couch, coffee table, chair, side table, lamp, rug, art and “accessories”), an explanation of the word “baking.” The other half is a trend-spotting guide to our Jane Jetson future. Each chapter ends with a look at possible coming technologies for each room in the house: digital wallpaper, dining tables that serve you your cereal, 3-D printers for clothes, kitchen knives that read the nutritional information of the food they’re cutting. Needless to say, this half is more engaging.

The whole thing has a shellacking of tech lingo and aesthetic. Commonplace domestic tips like boiling coffee grounds to deodorize a kitchen or using clear nail polish to fix a run in your tights are described as “hacks.” Every chapter has a “Tech to Know” section of useful apps. For the “Bathroom” chapter, suggestions include Nailsnaps, an app that lets you create stickable nail art, and Plum Perfect, an app that recommends beauty products to go with your individual skin tone. (Disclosure: I have downloaded this just now. It’s kind of genius.) Other DIY tutorials nod faintly to tech geekdom: using colored contact paper to create a pixel pattern on your coffee table, for example.

Morin’s shtick has not made her beloved in Silicon Valley, where the prickly nerdboys who run things seem to view her as the dreaded “fake geek girl”—the Homecoming Queen who dons the vestments of geek culture because they’re now cool. Morin has been repeatedly pilloried by the Silicon Valley gossip blog Valleywag, which mocks her as “Silicon Valley’s favorite camp counselor” and “Senior Vice President for Doily Engineering.” Valleywag has also accused her of plagiarizing ideas from other lifestyle sites. The nicknames are nasty (not to mention sexist), and the plagiarism charges seem rather beside the point. Using a cereal bowl to amplify the music on your phone is a neat, lightweight trick, not a patent technology.

This criticism is excessive, but it does point to Morin’s major failing. While claiming to speak to the digital generation, her book doesn’t demonstrate much confidence in women’s technology aptitude. How many adult women need definitions for words like “smartphone” (“they can connect to the internet”) or “GPS”? Morin herself has worked at Apple and Google, knows how to code and operate a 3-D printer, and says she thinks nothing of throwing together an app in her spare time. A book that combined domesticity and Morin’s genuine tech know-how would have been most welcome. Looking through other websites, there are a plethora of DIY domestic tech projects weightier and more interesting than making neon macramé plant-holders. Across the Internet, makers are using the $35 Raspberry Pi microcomputer to automate their home’s lights, make automatic dog treat dispensers, and create voice-activated coffee makers. You can make speakers out of Mason jars, and USB chargers from an Altoids can. You can knit your own touch-screen gloves or 3-D print your own cookie cutters. DIY technology and DIY domesticity are marrying in all kinds of fascinating ways.

A recent study from Intel suggested that maker culture is an ideal way of introducing girls and young women to STEM fields, where they are seriously underrepresented. “Girls who make, design, and create things with electronic tools develop stronger interest and skills in computer science and engineering,” the study reported. Many in the tech world are already on it. Several all-female maker spaces have opened in recent years. And the Oakland-based nonprofit Techbridge recently launched a summer maker program for girls. The girls sew circuits, brainstorm how to “hack” every day household items, and use social media to describe their experiences. Maybe one day one of them will grow up to write a book.