On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in King v. Burwell, which will decide whether health insurance subsidies should be available nationwide or only in those 16 states that established exchanges. Several questions have recently emerged over the legitimacy of the plaintiffs’ case, including issues of jurisdiction and congressional intent, but there’s an even deeper flaw: The plaintiffs’ interpretation would render the statute unconstitutional.

Several of my colleagues and I made this case in an amicus brief to the Court. If the plaintiffs’ interpretation carries the day, then Obamacare has threatened states that failed to establish exchanges with virtually assured destruction of their individual insurance markets. And the Supreme Court held in the first Obamacare case that the federal government may not make that kind of extreme threat. Congress can't hold a gun to states’ heads in order to force them to implement federal policies.

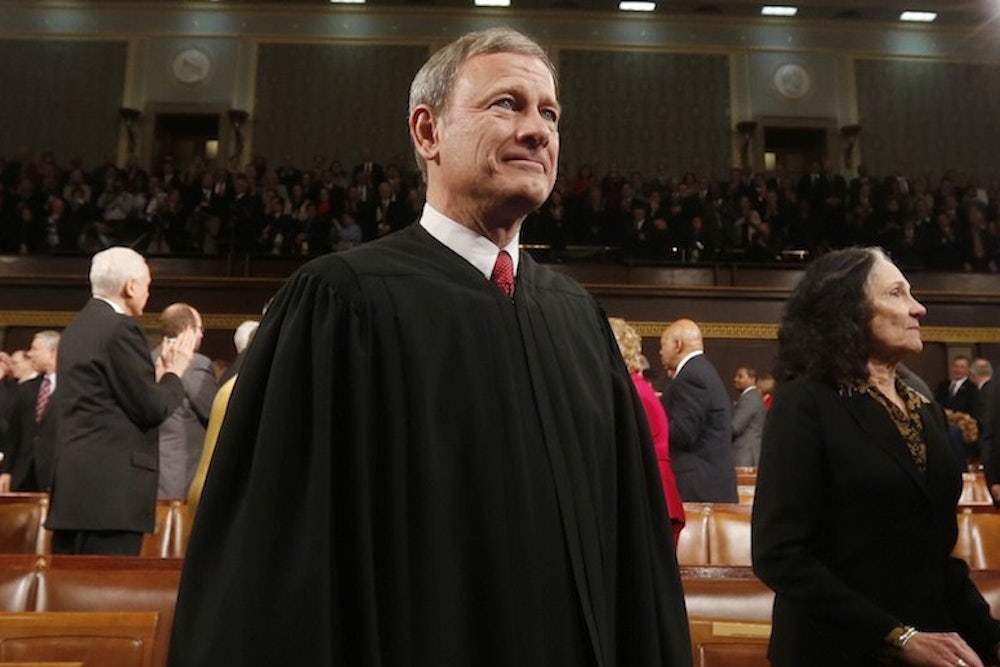

This constitutional problem matters—maybe more than any other flaw in the plaintiffs’ case—because it puts the conservative justices in a bind. In general, conservative justices try to avoid second-guessing a statute’s text, even if the text leads to seemingly crazy results, and the plaintiffs have a case that the text of the Affordable Care Act compels their victory. But some conservatives on the bench, notably Chief Justice John Roberts, are also dedicated to a different and sometimes-contradictory principle: that they should not assume that Congress wrote an unconstitutional statute.

In King, the outcome depends entirely on which side persuades the conservative justices of the Court; the four liberal appointees are likely to vote for the government. That’s why the plaintiffs and government alike have focused so much on the statute’s text, arguing that it supports their interpretation. The textual argument centers on a provision in the law that says the subsidy amount should be calibrated to the cost of insurance purchased through an exchange “established by the state.” Petitioners argue that Congress included the words “by the state” in order to limit the availability of subsidies to citizens in states the chose to establish their own exchanges rather than relying on the federally created exchange. The government counters that the words “by the state” are a term of art, meaning an exchange established in a given state—whether established by the state or by the federal government. But if the government’s interpretation is correct, those three words serve no purpose.

To the liberal justices, rendering a few words superfluous in an arcane, out-of-the-way provision of a 900-page public law will seem like no big deal. The government’s reading is much more consistent with the statute’s purpose of nearly universal, affordable healthcare; it’s a fairer reading of the provision in context; and it avoids a lot of perverse policy consequences (like the total destruction of some states’ health insurance markets). Most importantly, given the statute’s full text and structure and given its birth history, the government’s interpretation is clearly what Congress intended. Those three words seem to have been included by mistake.

But the conservative justices are loath to conclude that Congress messed up. It's not that those justices think Congress is perfect, but they do believe they should limit themselves to reading Congress’s words, not its mind. A statutory provision that looks crazy to the justices might not appear crazy at all to a senator, who must answer to a constituency, a president, a political party, and hundreds of colleagues. So the justices, according to this conservative impulse, should simply enforce the words—and all of the words—of a statutory text, even if those words lead to seemingly strange or even perverse results.

Applying that philosophy to King, the conservative justices are likely to ignore the bad policy consequences and the violation of statutory purpose that arise from the plaintiffs’ interpretation—not because they are politically conservative but because they are judiciallyconservative. But the constitutional problem with the plaintiffs’ interpretation—unlike the policy problems—triggers a different, contradictory, and often strongerconservative impulse.

The same basic judicial philosophy that compels justices to ignore policy consequences also compels them to take constitutional consequences very seriously. At least some of the conservatives on the Court believe that they should, at all costs, avoid rendering statutes unconstitutional through judicial interpretation. That’s why Roberts voted for the government in the first Obamacare case. He was willing to interpret the individual mandate as a tax in order to avoid striking it down, even though Congress and President Barack Obama had said during the law’s passage that the mandate was not a tax. Roberts was willing to stretch the statute a bit to avoid invalidating Congress’s work.

Remember, the justification for ignoring bad policy consequences of a weird statutory text is that justices should not second-guess Congress’s choices. They should enforce text even if it looks weird. But if a statute’s text is (or even might be) unconstitutional, then the justices will have to second-guess Congress’s choices. It’s the Court’s job to invalidate laws that overstep constitutional bounds. So, in King, the same basic philosophy that would motivate the conservative justices to give effect to the words “by the state”—even if those words seem to be there by mistake—should motivate Roberts to ignore those words if they would cause a constitutional problem. And those three words would.

Here’s the optimistic clincher: Between these two warring conservative impulses—between the impulse to ignore bad policy effects and the impulse to avoid unconstitutional outcomes—it’s extremely likely that the avoidance of constitutional difficulties will win. It’s a lot more disrespectful of Congress for the justices to conclude that the legislature wrote an unconstitutional statute than it is to conclude that Congress made a typo.