It has always been a secret fantasy of mine to appear in one of those massive art-world roundups of bright young things. There was only one factor preventing me from living my dream: a complete and utter lack of artistic talent.

So you can imagine how pleased I was when, a few months back, I received an e-mail from an artist named Martine Syms, a 26-year-old Angeleno looking for materials to inform her television-themed project for the New Museum of Contemporary Art’s 2015 Triennial. I had just published a book on the history of American sitcoms, and after disappointing Syms with my near-total lack of “Roseanne” lunchboxes or annotated copies of Dick Van Dyke’s memoir, I gladly handed over some photographs and spiral notebooks. (If anyone needs to consult my musings on all 98 episodes of “Gilligan’s Island,” text me.)

A few months later, Syms wrote me to say that after some halting experiments with photographing and scanning my notes, nothing seemed quite right. She had decided, instead, to simply place my notebooks behind glass, subject to the same care and consideration as, say, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

It wasn’t just my scrawled notes that were making a belated appearance in the rarefied world of the New York City museum show; it was television itself. Syms’s art springs from a background likely familiar to most millennials: “I grew up watching tons and tons of television,” she told me. “It was all I would do, especially during summer vacations.” A few years ago, she began thinking about the perpetually critically beleaguered sitcom, whose evolution, she notes, offered a historical primer in television history. Her piece for the triennial, “S1:E1,” combines original video work with materials from past New Museum exhibitions that touched on television—transforming pop culture into art, and making over the museum into a space open to the blandishments of television.

The moving image has been part of high art for decades, of course. In the 1960s, Andy Warhol famously stripped film of its relentless urge to entertain, and insisted on its capacity to simultaneously bore and transcend its own boredom; he pointed his camera at a sleeping figure, or the Empire State Building, and walked away. Other artists plumbed film for symbolically freighted images. Found-footage pioneer Bruce Conner’s landmark A Movie pooled together stag films, galloping horsemen, demolition-derby racers, tightrope walkers, and war footage into a collage in which nuclear holocaust is the inevitable outcome of a degraded, atomized civilization. Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle deployed dreamlike depictions of Greek gods enveloped by flocks of birds, topless bathing beauties in Art Deco headgear, and blimps on leashes, to empty film of narrative and allow it to take flight. Christian Marclay’s 24-hour film installation, The Clock, further confounded our movie-bred expectations for resolution with a bravura act of film scholarship: The work assembled a pastiche of clock-watching scenes from older films so that the time onscreen always lines up with real time. (“It was a greater challenge for me to resist the will to integration than to combine the various scenes into coherent and compelling fiction,” muses Ben Lerner’s protagonist in his new novel 10:04 as he watches The Clock.)

Throughout the decades that film has appeared in the museum, however, television has remained mostly beneath contempt. Those artists who turned to television were mostly dedicated to critiquing its shallowness. Nam June Paik’s influential 1965 work Magnet TV was a demonstration of the hazy images that would appear onscreen as a result of placing a giant magnet atop a television set—a distortion of a distortion. Otto Piene and Aldo Tambellini’s 1968 video Black Gate Cologne, which drew on images from American television broadcasts, featured fuzzy, hazy, scratched-up versions of news coverage of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, combining avant-garde practice with a critique of television’s banal platitudes.

But a new collection of artists is interested in television as the new film: a fount of cultural memory and a direct line to the national subconscious. In 1990, a show called “From Receiver to Remote Control: The TV Set” at the New Museum (which Syms draws on for “S1:E1”) featured, significantly, a kind of confessional booth in which visitors could speak openly about their most cherished TV-watching memories. But the celebration of television’s trashiest corners probably began in earnest with the work of Ryan Trecartin. His 2011 exhibit at MoMA PS1, “Any Ever,” was crammed full of cacophonous, deliberately garish video installations with wildly exaggerated, helium-voiced characters who sang, danced, sniped, and tormented each other—hysterical grotesques overinvested in interpersonal clashes. In short, Trecartin was reorienting reality television, stripping it of its content, and leaving only the sensation of free-floating melo-dramatic excess.

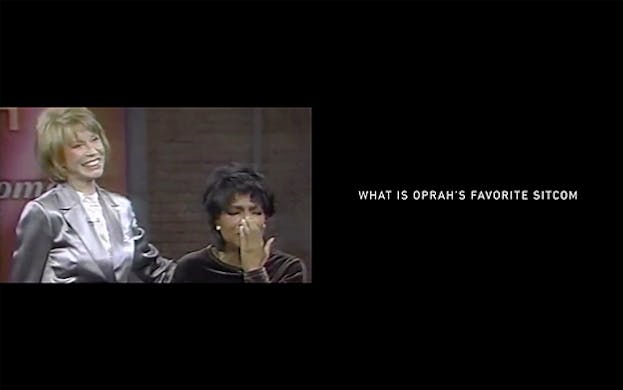

Like Trecartin—who is the co-curator of this year’s triennial—Syms is not just interested in television, but in a particular subset of degraded contemporary television: the sitcom. The centerpiece of Syms’s New Museum installation is a 25-minute hopscotch through the history of representations of African Americans in sitcoms titled A Pilot For A Show About Nowhere. The clips culminate in an imagined sitcom of her own called “She Mad,” which betrays a sense of dissatisfaction with the limitations of the form, even as she takes pleasure in its triumphs. “The Cosby Show,” for instance, was superlative, but Pilot argues that it also turned a blind eye toward the crises of crack cocaine, AIDS, and tough-on-crime policing that ravaged the black community during the very years the show sat atop the Nielsen ratings.

Also included in this year’s triennial is Casey Jane Ellison’s Web series “Touching the Art,” which lavishly mocks the art world’s pretensions at the same time that it pays a kind of tribute to the talking-head yakfest. The mock-roundtable show includes real art-world luminaries including photographer Catherine Opie and multimedia artist A.L. Steiner, with Ellison playing the Stephen Colbert–esque buffoon whose genial idiocy allows some serious ideas to be batted around. Like Colbert, she is mocking the jargon and vernacular of the art world even as she playfully creates a space for genuine dialogue.

Television—it seems—is the new lingua franca, its comforting familiarity allowing for conversation between high and low, past and present, sound and image.

Ellison’s and Syms’s work serves as a blunt metaphor for what TV lovers have been talking about for a number of years: TV is now high art. It is now on regular display in our living rooms and the subject of our fascination and debate. (On a European trip to see a friend, Syms was struck by a dinner companion’s comment that when Americans got together, all they liked to talk about was television.) We no longer shuffle into confessional booths to profess our love of television: We shout it proudly from the Twitter rooftops. We are all curators at the Museum of TV now.

Television—and even notebooks about television!—is now in museums, honored, respected, and treated with dignity. This is undoubtedly a good thing, overriding the art world’s longstanding hostility and suspicion toward what it saw as a junk-food medium. That dismissal has mostly faded, but the triennial’s reorienting of television for the museum may create a useful discontinuity, causing the still skeptical to reconsider the now arbitrary separation of American culture into non-overlapping high and low categories.

And yet this elevation—in our homes, in our museums—may also stifle the unprecedented burst of creativity that caused television to triumph in the first place. I wonder if our burgeoning understanding of television as high art—its literal and metaphorical enthronement in the museum of American culture—might also spell the end of the remarkable hot streak we have all been witness to. Can TV continue to impress us when it grows self-conscious of its own value? I am worried that perhaps we are all burning out TV by loving it too much. Will the next “Sopranos” or “Breaking Bad” flourish while we pant in front of our TV screens, expecting to be amazed?

The burst of creativity that took place in the 1990s and 2000s transformed the “boob tube” into the richest node of contemporary American culture. But the ground was fertile, at least in part, because there was not yet a television pantheon—no set bundle of modern classics to imitate. Since then, television has gotten so great that it has become ever so slightly afraid to settle for just being good. Quality TV has gone from being an expression of praise to a defined genre, with recent misfires like “The Newsroom” and AMC’s early-years-of-personal-computing drama “Halt and Catch Fire” feeling like focus-group-tested applicants to the TV Hall of Fame.

The misfires are still far outweighed by the successes, and our DVRs groan with endless TV bounty. But golden eras have a funny habit of ending just as we begin to get used to them. Television needs room to grow and change and adapt and surprise, not be hemmed in by the well-meaning but suffocating love of a nation of freelance curators assembling their collections on their DVRs and Netflix queues, demanding a new “Mad Men” every month, but getting only pallid imitations.

By every critical measure, 2014 was a great year for television, but it was an especially great year for comedy on TV. Some of those shows, like “black-ish” and the late, lamented “Enlisted,” felt like updates of familiar sitcom styles, but others, like “Review” and “Broad City,” created entirely new models that felt like nothing that had ever been on television. And then there were series like “Transparent” on Amazon and the wonderful new “Togetherness” on HBO, which eschewed a uniform mood or style, and thus refused to let their audiences settle into a cookie-cutter, quality-TV rut. They were sometimes serious and often funny, simultaneously cutting and moving, a deliberate grab bag of fart jokes and social commentary. They were, in short, middlebrow heaven: a place where the human comedy could momentarily exhale.

Perhaps there is actually not much to fear about this particular chapter in the enshrinement of TV as art, at least as it’s playing out in the museum. The triennial has made room for television, not just as prestige works of aesthetic refinement, but also by embracing the middlebrow pleasures of comedy and satire. Before television makes itself over as an entirely self-serious art, let us hope it can take a page out of Syms’s and Ellison’s work and maintain a wing of its museum in which the middlebrows can go on romping forever.