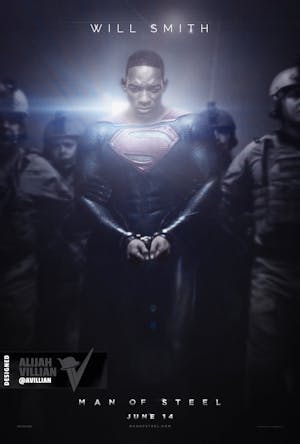

In January, Alijah Villian's digital art project "Black Superheroes Reimagined" returned, in classic superhero fashion, for a second installment. The concept is straightforward: Villian photoshops black actors into posters for superhero films starring white actors. Will Smith is the Man of Steel. Idris Elba replaces Daniel Craig as 007. And Sanaa Latham, not Scarlett Johansson, is Captain America's Black Widow.

"There is a lack of diversity in film and television all the way around," Villian wrote in a post explaining his project. "One could argue that television is showing improvement at a faster speed than film. Especially, when we start talking about Superheroes. Not sidekicks, thugs, or villains, or any supporting characters. It seems we have a lot of work to do."

It's valuable to imagine an American cinema in which the iconic heroes are black instead of white. And as Villian's project makes clear, it's not that hard to imagine it; there are plenty of talented black actors who deserve such role. But simply replacing white actors with black actors, while important to the diversification of Hollywood, would nonetheless be a rather superficial move. After all, a black superhero could have different priorities than a white one.

Superheroes are usually avatars of law and order; they fight crime. But our country's massive criminal justice system, from "broken windows" policing to sentencing disparities, discriminates against African Americans. A black superhero, then, could be so much more than an African American actor in a white superhero's costume. Black superheroes could challenge the entire genre itself.

For the most part, they haven't done so. X-Men: Days of Future Past borrows from the history of racial genocide, but its actual black characters, Storm (Halle Berry) and Bishop (Omar Sy) are no different than any of the oppressed white folks, except with smaller parts. When DC Comics debuted Black Lightning in the late '70s, the titular character fought crime in Metropolis' Suicide Slum. The notion that Superman's Metropolis even had a slum was, perhaps, an acknowledgement of racial and class disparities. But as Osvaldo Oyola points out, "whatever promise was present in its setting and exploration of racial politics of superhero genre remains untapped." Lightning just bashes supervillains, like any white superhero. Christopher Priest's run on Black Panther tries to shake off the usual genre default by making its main character the ruler of a super-advanced African nation, but the initial arc of the series has him wandering around New York, hitting criminals. As James Lamb wrote in a post acidly titled "Superman Is a White Boy":

Race and gender minority superheroes present pale knockoffs of the White male power fantasies that transcended comic panels decades ago. What was Manhunter but a low budget Nightwing who replaced the tonfa with a glowing metal rod? Under Reginald Hudlin’s pen, Black Panther explicitly devolved into an African Captain America, known more for marrying [Storm,] the most famous African superhero in American comics than his own exploits…. In our world, the most famous, most powerful, most influential superhero ever devised is a straight White man. Here, meaningful diversity in superhero comics is not possible. The superhero concept is a racial construct, used primarily to derive profit from printing White male power fantasies ad nauseam for a core audience of ostracized children.

If Superman is a white boy, and superheroes are a white power fantasy, are distinctively black superheroes even possible? In science fiction, writers like Marge Piercy and Samuel Delany have used non-white characters, and non-white history, to challenge the genre and upend some of its colonial preconceptions. The superhero genre has never really attempted a similar project, at least not in the mainstream. But if you look further afield, there are some interesting possibilities.

Octavia Butler's 1980s science-fiction trilogy Xenogenesis is set in the far future, after a nuclear war has destroyed the earth. Tentacled aliens, the Oankali, have rescued the few remaining survivors. The Oankali are genetic manipulators; they save the humans in order to breed with them. The central character of the first book, Dawn, is a black woman named Lilith, who takes Oankali mates. The final book Imago, is the story of one of her children, Jodahs, who is the first human-born ooloi.

Ooloi are a four-armed third gender. Jodahs is not just an ooloi, though. Jodahs is a black superhero.

Like Superman, Jodahs is an alien invader with spectacular powers. It has remarkable healing abilities; its mastery of genetics and its own body allows it to repair even repeated bullet wounds almost instantly. It can also heal others, repairing wounds and even rewriting and correcting genetic illnesses. It can shape-shift. And it can seduce; it has a kind of super-pheromone, which makes men and women alike love it, trust it, and (ultimately) want to mate with it.

Obviously, this is a very different superhero story than what you generally get in your summer blockbusters. In the first place, there aren't any supervillains—or rather, Jodahs is both supervillain and superhero.

If there is an enemy, it's not some monster with superstrength, but rather the human nature that sees the other as a terrifying monster. "Humans were genetically inclined to be intolerant of difference," Jodahs muses. That's why humans blew each other up in a nuclear war, and it's why many of them have trouble accepting the Oankali's offer of miscegenation, even if such mixing results in superpowered children. The humans have no hope of defeating the Oankali; the only question is whether humans will go on futilely killing themselves (on earth or in a colony the Oankli offer on Mars), or whether they'll accept the Oankali offer of peace and union (and tentacle sex).

The theme of merging or union is typical of superhero narratives. The story of Superman, to pick the most iconic example, is in many ways a story of assimilation to whiteness. Jewish creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster imagined an alien arriving in the U.S. and becoming the ultimate icon of white male Americanism. Butler's superhero, though, doesn't assimilate to whiteness. Rather, it transforms whiteness so utterly that categories like white and black, gay and straight, male and female, and even humanity itself blur and lose their meaning. Jodahs is not a model minority like X Men's Professor Xavier, who polices others on the margin for the greater good of the mainstream. Instead, the black superhero's powers let it rewrite the rules of mainstream respectability. Love replaces violence; strangeness becomes desirable; the feared, hated thing becomes family. Jodahs' power is, literally, to end racial animus, not by adopting a pose of whiteness, but by iconically embodying and proselytizing difference of race, gender, sexuality, and even species. Difference for the Oankali isn't eliminated; it is embraced and used. Each Oankali is essentially a different species, genetically, from every other; each is a unique mix of genetic material from multiple races. To be Oankali is not to be any particular genetic type, but is instead to accept a community in which family members are all of different genetic types. Jodahs' superheroic power is to create love out of difference.

Butler's take on superheroes highlights the way in which the genre has always, to some degree, contradicted Lamb's view of it as a white power fantasy. The hate and fear faced by the insectoid Spider-Man, or the deformity of The Thing, can be seen, in light of their creators ethnicity, as markers of immigrant, Jewish, or racial difference—an echo of Jodahs'S powerful, admirable, frightening alienness. But Butler also highlights the pallid timidity of the superhero genre. It took four decades for the comics to openly acknowledge The Thing's Jewishness; even though the genre was originally pioneered by ethnic minorities, discussions of race were tip-toed around and smuggled into the narrative via metaphor.

In superhero comics, blackness—or race itself—is very rarely used to challenge the genre's default support of law and order, or of assimilation. The fact that, in Butler's Xenogenesis, it took an apocalypse and the utter destruction of earth for a black superhero to emerge and challenge whiteness is perhaps telling. Jodahs shows both what a black superhero could be, and what sort of revolution would have to occur for such a character to ever make it onto a movie poster.

This article has been updated.