I never look forward to Black History Month. There has always been an uncomfortably apologetic air to it, as if these are the 28 days designated for empty racial recompense. As a black kid, it’s the time when you might see images of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks stapled to your classroom corkboard along with with red, green, and black paper and shiny letters spelling out “We Shall Overcome.” You could even find yourself singing that song with your classmates, twitching every so slightly as others glance at you as if for your blessing.

Recognition of our forebears does matter, and it's welcome when they are not used as a commercial for American racial progress. But Black History Month has become a platitudinous moment, representative of so much said and much less done.

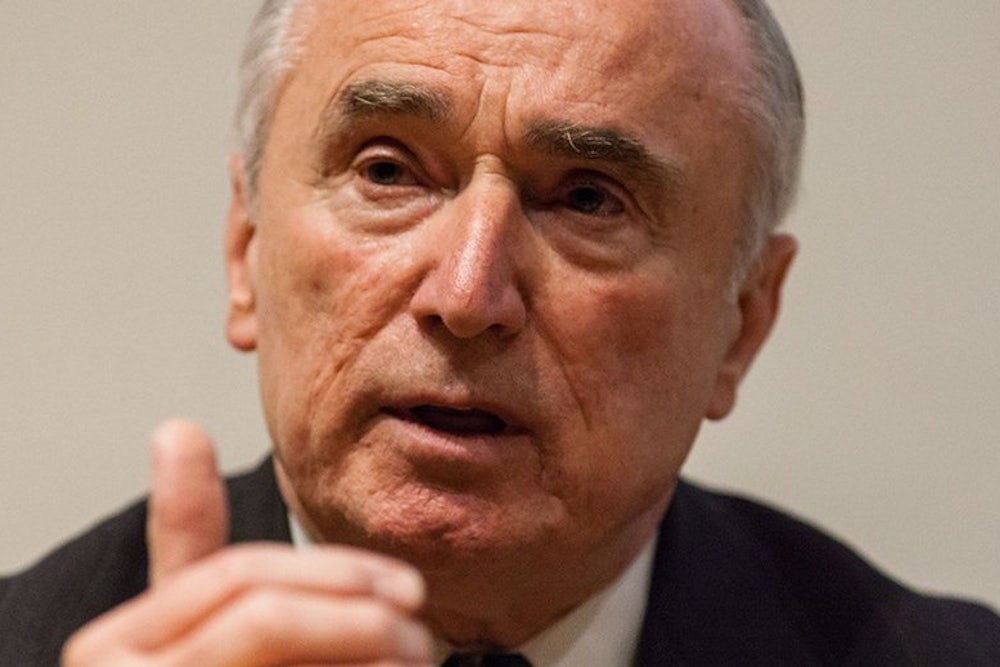

I was reminded of that today, when New York Police Department Commissioner William Bratton addressed an African Methodist Episcopal church in Jamaica, Queens. Bratton, whose already beleaguered reputation in communities of color took a major blow when one of his officers choked Eric Garner to death last July, made remarks that would be startling coming from any police commissioner. Business Insider reported that after Black History Month boilerplate name-drops of King and Parks, the commissioner uttered these words to the predominantly black audience:

"The best parts of American history would have been impossible without the police. Many of the worst parts of black history would have been impossible without police, too."

Bratton followed that up with a history lesson about Peter Stuyvesant, one of New York’s earliest settlers and the founder of the city’s police force, who used slaves. He noted “deepening racial divide in this country—a divide we thought we had healed,” and that “the NYPD needs to face the hard truth: that in our most vulnerable neighborhoods, we have an issue with police satisfaction.”

It isn’t the first time Bratton, in the midst of the city’s heated racial climate, has addressed these concerns; the day after the funeral of murdered officer Rafael Ramos, he told Meet the Press host Chuck Todd that he recognized the “reality” of African American concerns and fears about police. A recent New York Times report indicated that Mayor Bill de Blasio and a police union head are getting along again—some might argue too well—after a winter that saw citywide protests against cops and demonstrations by police at the funerals of two slain officers. Given that, it seems only decent and politically smart for the city’s top cop to offer an olive branch to a constituency that has been brutalized physically and emotionally by a number of the officers he leads.

Still, Bratton was addressing the wrong audience. The commissioner’s remarks are not unlike those given nearly two weeks ago by FBI director James Comey to a collegiate crowd at Georgetown University in Washington. Both men spoke to people who may have been personally assuaged by the words, but who are virtually powerless to help those words become the action or reform that law enforcement agencies need. Both speeches amounted to little more than rhetorical reparations, mere recognition that wrong has been done in the absence of a plan to prevent future Eric Garners and Akai Gurleys. Both should have addressed the people who can actually change the culture of policing: the officers and agents under their command.

It is also a fairly easy placation, particularly during the time of year our country sets aside for such confession, to state the obvious: Law enforcement has authored some of the most brutal and murderous chapters of African American history. That speech is more difficult to swallow when considering the 4,500 words Bratton spat forth in December fervently defending the ineffective “broken windows” tactic he champions, even as New York’s communities of color are disproportionately targeted. Even Bratton can contain multitudes, but which words are meant to signify his true intentions? Inherently, it seems impossible that he can denounce past police evils and while he praises a policy that increases the likelihood of future discrimination by police. For real progress, some of the NYPD's (and FBI’s, for that matter) actual enforcement practices will have to be reformed and, in the case of “broken windows,” scrapped.

Bratton may have intended no malice on Tuesday, but he only fed us a line—just in time for the end of Black History Month. Yes, at least it’s more than what we’re hearing out of Chicago, some may say, where The Guardian’s Spencer Ackerman today reported that police have secret rendition sites, the kind of thing we hear about our government doing in overseas war zones. It’s certainly more than what we’ve heard out of my native Cleveland, where a police union head told columnist Connie Schultz that 12-year-old Tamir Rice, with only a pellet gun in his waistband, was “in the wrong” and “menacing” for those two or so seconds before he was gunned down by a rookie cop. But if Bratton's words are exceptional only amid modern-day police horrors and other officials' silence, I’m unsure how many black-allyship cookies Bratton really deserves.

“We celebrate how far we've come, and we recognize how far we have to go,” Bratton said. That’s true. But black New Yorkers already get that. Do his officers? I don’t need Bratton’s repeated assurance that he understands the past trauma of black interactions with police. I’ll be more encouraged by practical, transparent steps taken to ensure his officers don’t interrupt black futures in this city.