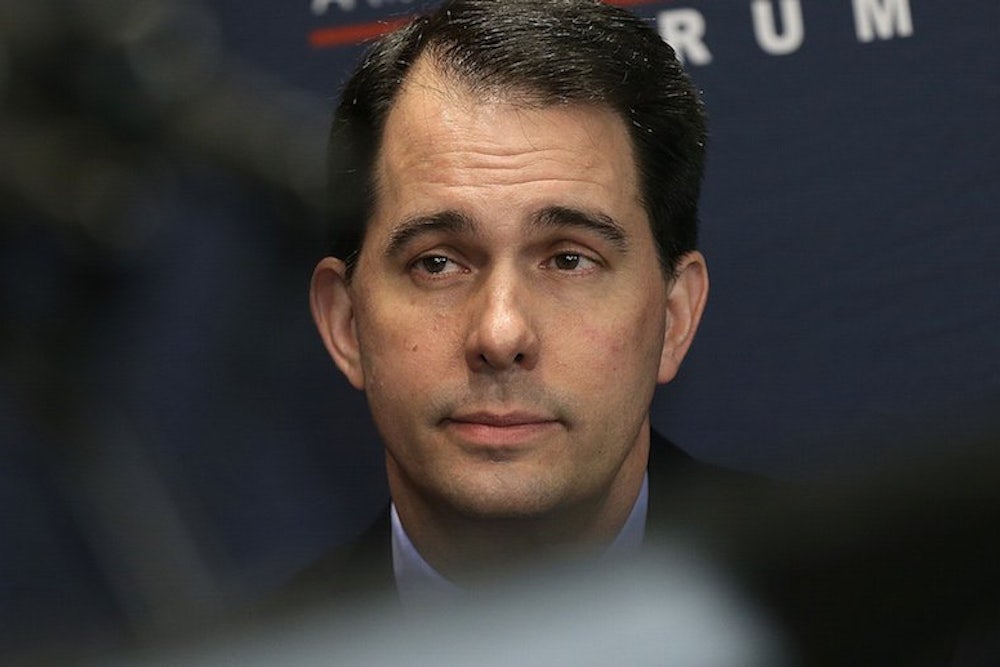

The Republican non-response is having a moment, this time in the context of President Barack Obama’s religious convictions, which are up for review once again. First, after former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani bizarrely accused Obama of not loving his country, Republican governors Scott Walker and Bobby Jindal refused to disagree. When asked in an interview Saturday whether or not Obama is a Christian, Governor Walker again demurred, saying “I don’t know.” Though Walker was evidently reminded during the interview of Obama’s public remarks about his Christian faith, Walker still insisted it is impossible for him to know whether or not the president is a Christian. He also registered frustration with the entire line of questioning.

On one hand, Walker’s refusal to commit to an answer is in line with other Republicans' non-committal statements about Obama’s interior life. In that light, it is possible to read Walker as signaling a certain contingent of the conservative electorate that vehemently denies Obama’s Christianity. On the other hand, there’s also a sense in which, all dog whistling aside, Walker is exactly right.

Attempts to prove or disprove Obama’s religious commitments encounter a special set of problems. Foremost among them is the fact that, despite the American public’s general familiarity with Christianity, we have no public consensus as to what constitutes a Christian. One can see the different methods of discerning what makes a Christian play out in the different endeavors to prove or disprove Obama’s faith. Right-wing news outlets like Breitbart were quick to blast Obama for misquoting a Bible verse last December, using the mistake to bolster a conservative narrative in which the president’s faith is an opportunistic façade. But if thinking on politics through the lens of faith is un-Christian, then Pope Francis is not a Christian either; and if lacking a photographic memory of the entire Bible verbatim excludes membership, then most priests, pastors, and theologians are also out of the Christian club, along with children, babies, and the world’s illiterate.

Earlier this month, Erick Erickson, editor-in-chief of RedState, announced that Obama cannot “in any meaningful way” be a Christian because the president made the following remarks at this year’s much-discussed National Prayer Breakfast:

“I believe that the starting point of faith is some doubt —not being so full of yourself and so confident that you are right and that God speaks only to us, and doesn’t speak to others, that God only cares about us and doesn’t care about others, that somehow we alone are in possession of the truth.”

For Erickson, Obama’s suggestion that others might be in possession of truth is evidence that the president does not adhere to the idea that Christ is Himself the truth, as stated in the Gospel of John. This amounts, in Erickson’s thinking, to proof of Obama’s moral relativism, despite the fact that the next sentence in his speech was: “Our job is not to ask that God respond to our notion of truth.” Nonetheless, Erickson’s method of disproval displays his understanding of Christianity as rooted in a certain attitude towards the Biblical text and its literal primacy.

Meanwhile, Breitbart has implied Obama’s alleged faithlessness by questioning the first family’s lack of regular church attendance, and hinting at supposed discrepancies between the different explanations for the same. For some, then, Christianity is a matter of ritual and participation rather than Biblical literalism or textual recall. Yet even if someone attended church regularly, could recite the Bible by heart, and professed the entirety of it to be literally true, the problem of belief would remain. Conversely, if someone believed in God and Christ the savior, a whole wealth of doctrine would remain unsettled as grounds upon which to assail their faith. Such has been the history of Christianity, after all.

And so Walker is probably right: Without knowing Obama personally and having enough of a relationship with him to both probe his convictions and develop an intuition of his beliefs, it is impossible to begin to forward an educated opinion about whether or not he is Christian. More to the point, it is not even possible to advance a litmus test for proving his Christianity that the general public can widely agree upon, and even if it were, there is no reason to presume one’s Christian-ness can or should be decided democratically. In short, we lack the public agreement necessary to begin to decide how we would even know whether or not Obama is truly a Christian.

Back in 2008, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, then writing for The Atlantic, proposed that most presidents are probably heretics of one sort or another, and that a better question is what kind of heretics they are. Heresy and orthodoxy are certainly categories with better defined parameters than the broad label of Christian, but the development of heresy and orthodoxy as classifications have been, to some degree, matters of historical and political convenience, as Harvard Divinity professor Karen King points out in her book What is Gnosticism? Discovering whether or not a person’s professed beliefs align with particular heresies can tell us whether or not they are heretics, in other words, but it cannot answer definitively whether or not they have a relationship with God that can be described as Christian.

Given the infinite list of problems in externally proving a person’s faith, the decision to describe someone as Christian or not is usually a matter of prudence in achieving some sort of goal, religious or political. What is really at stake in the question of whether Obama is a Christian or not is what Christianity has been made to mean in this country, which is often little more than shorthand for political conservatism. The conservatives who refuse to acknowledge his Christianity seem bent on preserving this conflation of the right wing and Christianity for electoral reasons; the Obama advocates who oppose them would probably like to reveal them as judgmental hypocrites for the same purposes. But what the ongoing muddle in the debate about Obama’s Christian qualifications (along with a similar effort to establish the Islamic States' Islamic-ness) really reveals is that trying to assign religious labels, however politically expedient, is usually a foolhardy endeavor.