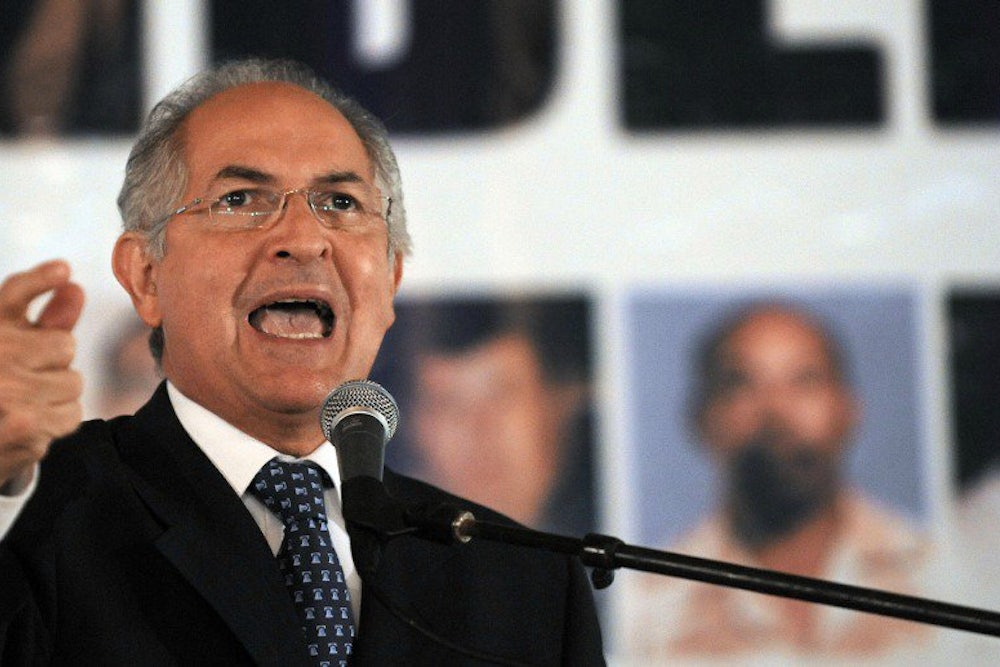

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro thinks the mayor of Caracas is involved in a United States plot to overthrow the country's government. That mayor, opposition leader Antonio Ledezma, was arrested on Thursday, adding tension to Venezuela’s already polarized society.

Rights and advocacy groups have already denounced Ledezma’s detention, and the Venezuelan opposition has staged protests throughout the South American country. David Wilkinson of Human Rights Watch’s Americas Division wrote on Twitter that the government must “show evidence linking Mayor Ledezma to an actual crime or grant him immediate unconditional release.” Ledezma was formally charged with “conspiracy to commit violent acts against the state.”

He now joins Leopoldo Lopez—a younger, more prominent opposition leader—who has been jailed since last year’s anti-government protests that shook Venezuela. That unrest left at least 41 people dead, including opposition protesters, government supporters, and security forces, according to HRW. Government officials say that some 41 people who participated in last year’s unrest are still in prison, though that number could be higher.

While most observers are highly skeptical of the evidence against Ledezma—which appears to be a national “transition” document he signed last week—he has been linked to fringe elements of the right-wing opposition which called for “La Salida” (“The Exit”) of Maduro in last year’s protests. According to Reuters, “student radical Lorent Saleh surfaced in a government-broadcast video praising Ledezma as ‘an old fox ... the politician who has most supported the resistance.’”

The decision to arrest Ledezma—which Maduro addressed in his three-hour televised speech—comes at a difficult time for the Maduro administration, and thus is widely seen as an act of diversion. It will likely serve to deepen the political crisis that is already gripping the country since the 2013 death of former President Hugo Chavez, the 2014 opposition protests, and the economic woes worsened by the fall in oil prices and manifested in food shortages and high inflation. Maduro’s approval ratings—currently at 22 percent—are at the lowest since taking office.

Given the various crises and Maduro’s low popularity, arresting an opposition figure is perplexing. George Ciccariello-Maher, a Political Science professor at Drexel University and author of We Created Chavez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution, told The New Republic in an email that “it could seem like a miscalculation for the government to arrest him.” But, he argues, the same could be said about Lopez, whose detention has earned Maduro deserved criticism from various international organizations. It has played out differently in the domestic sphere. “[T]he Maduro government puts the opposition in a tight corner: either denounce the violent radicalism of their own fringe or embrace it,” he wrote. Domestically, the opposition denunciations against Lopez’s detention haven’t gained as much political traction as abroad. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton called for Lopez’s release on Twitter on Thursday:

Leopoldo López and the political prisoners in Venezuela should be released without delay.

— Bill Clinton (@billclinton) February 20, 2015David Smilde, a Senior Fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), recently wrote that the result of the last 16 years, which saw institutions of justice dominated by Chavistas, is “a government in which the administration of justice is not only politicized, but also extremely inefficient.” Not that Venezuela’s justice system was anything to be emulated before Chavez. Smilde cites a 1998 survey which showed that “less than 1 percent of the population trusted Venezuela’s judiciary.” Clearly, as the reaction to this arrest shows, serious problems persist.

The U.S. State Department, for its part, has called the allegations of a coup plot “baseless and false,” adding that the U.S. “does not support political transitions by non-constitutional means.” No evidence has surfaced to support Maduro’s allegations. But to the State Department’s latter point, it is slightly disingenuous to suggest the U.S. is entirely anti-coup. It was aware of the 2002 coup against Chavez in advance, according to the New York Times, though they blamed Chavez for those events. The U.S. government initially endorsed the coup, but eventually had to backtrack when Chavez was brought back to power.