In July 2014, the Federal Reserve released a report that outlined the growing retirement crisis in America. Nearly a third of Americans over the age of 18 have no retirement savings. Twenty-three percent of those between the ages of 45 and 59 have no savings or pension. But the Fed report overlooked an key part of this problem: Minorities are in far worse financial shape than white Americans.

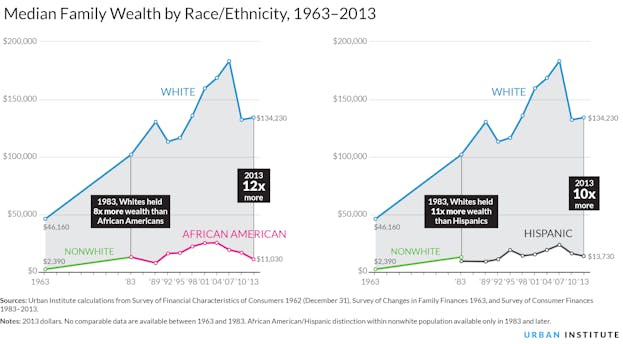

That’s the finding of a new analysis from the Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C. A team of five researchers put the data narrative together, which consists of nine graphs that outline why the retirement crisis is so much worse for African-Americans and Hispanics. The largest reason for this gap is that Hispanics and African-Americans build up less wealth than white families over their lifetime. The gap is only getting worse. In 1983, the median white family had more than $100,000 in wealth, compared to less than $13,000 for African-American families—an eight-fold difference. By 2013, the median white family had 12 times the wealth of the median African-American family. The same is true of Hispanic families.

By age 61, the median white person has earned $2 million over their lifetime. The median African-American and Hispanic have earned $1.5 million and $1 million, respectively. The higher lifetime earnings allows white to save more, and those savings earn more interest—wealth begets more wealth.

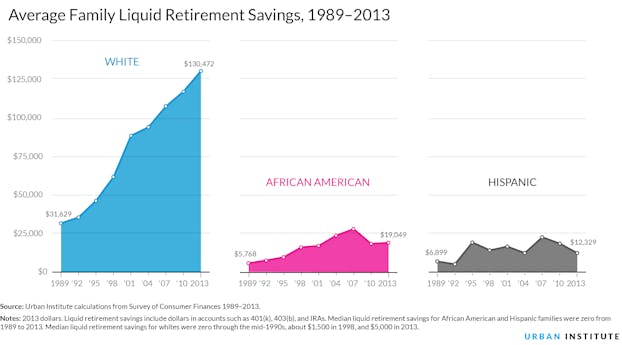

This gap is also apparent in average liquid retirement savings, which the researchers define as including “dollars in accounts as 401(k), 403(b) and IRAs.” These are common vehicles for retirement. The Fed study found that 43 percent of Americans are using a 401(k), 403(b) or other defined contribution pension plan through an employer. Another 23 percent of Americans have an IRA (some have both). It’s important for families that they have some liquid retirement savings. It’s always great to build up wealth in a house. But you don’t want to have to sell the house to afford basic needs during retirement.

The Urban Institute report reveals just how little African-American and Hispanic families have in liquid retirement savings, particularly compared to white families. In 2013, the average white family had more than $130,000 in liquid retirement savings, compared to $19,000 for the average African-American family and $12,000 for the average Hispanic family.

In some ways, this understates the retirement crisis for everyone—African-American and Hispanic families, as well as whites. The Urban Institute also looked at liquid retirement savings for the median family, not the average. That’s important because a few very rich people at the top of the income distribution can distort the statistics: Say 20 people are in a bar, each of whom make $50,000 a year. Then Bill Gates walks into the bar. Suddenly, the average income of each person in the bar skyrockets. But that’s just a result of Gates’s exorbitant income, not everyone in the bar getting richer. Using the median overcomes this problem.

“Median wealth shows how the typical person is doing,” said Signe-Mary McKernan, one of the researchers behind the study. “If you line everybody up in order, you’re just grabbing out that middle person and seeing how they are doing.”

And that’s where the liquid retirement savings data is most alarming. The median white family has just $5,000 in liquid retirement savings, up from $1,500 in 1998. For African-American and Hispanic families, the median is zero.

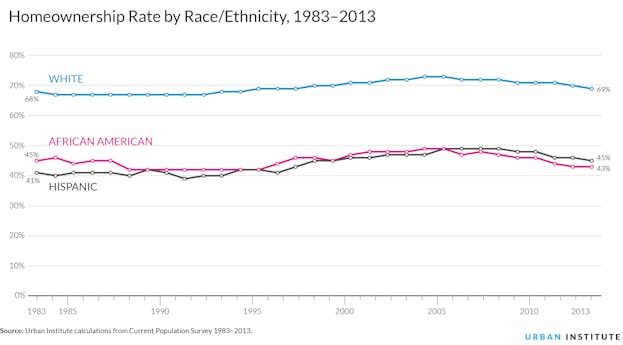

Minority families have trouble saving for retirement for two other reasons outlined in the Urban Institute study. First, they have lower homeownership rates, which, while not a liquid savings vehicle, is one of the most common ways that Americans save. More than 20 percent of Americans over the age of 60 have savings in real estate or land. But the homeownership rate for whites is more than 50 percent larger than the rate for African-American and Hispanic families—and the gap has stayed constant for the past 30 years.

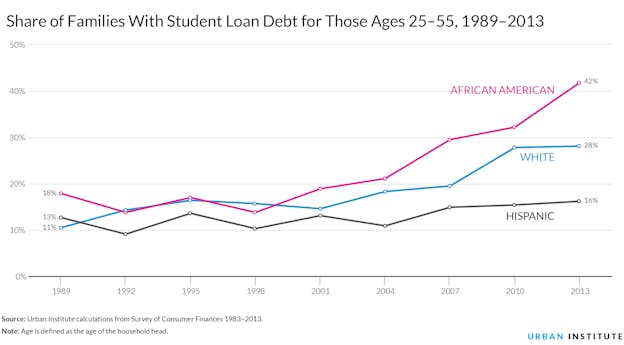

Second, African-Americans families have more student debt than whites. In 2013, 42 percent of African-American families had student debt, compared to just 28 percent of whites and 16 percent of Hispanics. And, as the Urban Institute authors note, African-Americans have lower graduation rates than whites and “people of color disproportionately attend for-profit schools, which have low graduation rates.” That means that African-Americans aren’t just taking on more in debt. They also aren’t always getting a degree for that debt.

The gap in retirement savings can't only be blamed on access to, or participation in, retirement savings vehicles. “In 2013, 47 percent of whites participated in employer retirement plans,” McKernan said, "and 40 percent of blacks and 28 percent of Hispanics [did]. Part of those difference in participation rates is access. But what surprised us is that while only 28 percent of Hispanics are participating in a plan, their average liquid retirement savings weren’t as different as African-Americans as we thought they’d be.

“It suggested to us that employers offering a retirement account isn’t necessarily going to fix it,” she added. “There needs to be ways to make those savings automatic.”

McKernan and her co-authors recommend six ways to increase retirement savings for African-Americans and Hispanics. They propose automatic IRA plans so that employers who don’t offer pensions automatically deduct a portion of their employee’s paycheck and deposit it in an IRA. The Obama administration has already approached such a proposal. A year ago, the president announced the creation of myRA accounts that would allow employers to offer retirement accounts to their workers (but not auto-enroll them in them). The program is just getting underway, but could provide an important way to get all Americans to save more.

The Urban Institute authors also want to limit the mortgage interest deduction, whose benefits accrue mostly to the top 40 percent of earners, and use the money for a tax credit for first-time homebuyers. I’m a huge fan of limiting the mortgage interest deduction, which encourages buyers to take on more debt and buy bigger houses. But I’m hesitant to use that money to offer a first-time homebuyers credit, which can also promote excessive homeownership and larger homes. That money could certainly be put to good use in other ways to ensure Americans have secure retirements.

Another smart idea is to offer a universal chidren’s savings accounts. The specifics of such a program can vary. In 2012, Phillip Longman, writing in The Washington Monthly, argued for accounts that the government automatically creates for the child at birth. Grandparents, parents and children can contribute to those accounts, with contributions capped at $2,000 per year. The funds would build up over time, accruing interest over the course of the person’s life. They wouldn’t be a solution to the retirement crisis—particularly for living Americans today without such accounts—but they could provide another level of protection in the future.

Most of McKernan and her co-author’s recommendations are focused on helping retirement savings for all Americans, not just minorities. That’s not a bad thing, but there are other things that the federal government could do that would help African-Americans and Hispanics in particular, like getting the economy back to full employment or ending the drug war. Millions of African-Americans are disproportionately locked up each year for non-violent drug offenses. Those criminal records make it much harder to find a job—and that makes it far harder to build savings and wealth over time. If Congress is looking for a way to close this racial gap in retirement savings, that would be a good place to start.