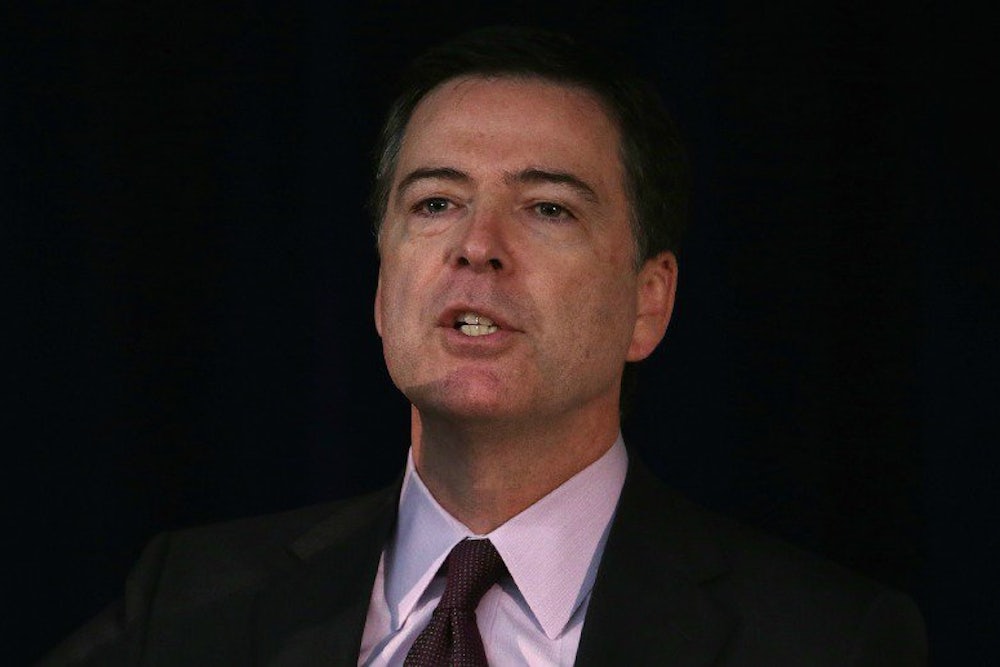

The FBI is sending Hallmark cards to black community leaders. That’s the sense I got today as I watched the bureau’s director, James Comey, speaking about race and law enforcement. The speech was nice. The crowd was pleasant, privileged, and polite. Georgetown University was an appropriately prestigious and academic site to deliver this half-measure talk on law enforcement’s systemic murder and brutalization of an entire segment of the population.

This was the first time an FBI director has taken the time to speak about race this directly. It didn't happen during civil rights bombings, nor through the Jim Crow era of lynchings, nor in apologizing for COINTELPRO’s systemic assassination of African American civil rights leaders, nor in reconsidering the bogus claims against Assata Shakur that laughably make her one of “America’s Most Wanted,” nor through the war on drugs that militarized local cops and destabilized black communities in the 1980s, nor through the plantation system of corporate prisons, nor through the rapid expansion of hate crimes against immigrants and Muslim Americans since 9/11, nor during the horrendously disproportionate amount of death threats and assassination claims against President Obama over the past six years. It's late, but it's a start.

The Guardian ran a solid timeline of his speech, "Hard Truths: Law Enforcement and Race," and the questions afterward. If you're looking to the transcript or the video for an earth-moving statement on race, you'll be disappointed. What you will see are a host of encomiums to law enforcement partway to acknowledging that cops' jobs—chasing criminals, being lied to all day, making flash decisions—can dim their view of humanity. (He also referenced the "Avenue Q" song "Everyone's a Little Bit Racist.") In this, at least, Comey's starting a serious conversation, even if it boils down to don't hate the players, hate the game.

"All of us in law enforcement must be honest enough to acknowledge that much of our history is not pretty," he said. And: "If we can’t help our latent biases, we can help our behavior in response to those instinctive reactions."

Even if the most profound aspect of the speech was Comey's choice to deliver it, he should be commended. He put words to paper recognizing the Kafkaesque tragedy black America has endured in urban areas since the great migration to the North in the early 20th century. While the South carried out its lynchings with ropes and white sheets, the urban North used badges and pistols.

Furthermore, Comey had to be the one to make this statement. We should take a moment to salute the recent fallen victims of "race discussions" who have tried to hold this sort of public forum. Attorney General Eric Holder received death threats from police for doing his job, when he opened an investigation into the Ferguson, Missouri police department. President Obama has tiptoed into this minefield a few times, reaping right-wing claims of race-baiting and left-wing deference to cops.

Remember when Prof. Henry Louis Gates was arrested for appearing to break into his own house? Obama made a simple remark about an internationally respected African American scholar's ability to enter his home without being arrested and paraded into a patrol car. Obama was excoriated; Gates was derided as an uppity intellectual for exercising his constitutional rights. Both esteemed men—one a Harvard scholar, one the leader of the free world—had to backtrack, stage a group photo-op with the white cop while sipping beers and smiling. It told America: "I’m not angry—look. I was just kidding about my rights."

Later we felt the public outrage of Trayvon Martin’s murder and the Sanford, Florida, police reluctance to so much as arrest the confessed and confirmed killer, George Zimmerman. President Obama remarked that Trayvon could be his son, as a sympathetic appeal to parents who do not want to see their children shot to death. Once again, the backlash silenced the most powerful man in the world. A vocal segment of America, it turns out, interprets anti-murder comments as anti-white.

We need white allies to step forward. We need them because a large population of destructively prejudiced citizens reject anything a woman says about rape and reproductive rights, or what a black person says about race, or what a Muslim says about peace. The words don’t penetrate.

Comey seeks to be that ally, to build a bridge Holder and Obama, because of their race, cannot. In gingerly stepping forward, he affirms that minority communities—not so far from Georgetown, in fact, but a world away—face unequal and deadly use of force.

Comey assumed the same submissive position that moderate leaders find themselves in during storms of right-wing insanity: Say something obvious about inequality. Make it clear that you love cops. Offer an anecdote about blacks and whites not being treated equally. Reaffirm your love for cops. Quickly utter the name “Obama” in a sentence with the word "admire." Last, be sure to mention for the back rows that, point of fact, you do love cops.

I’m processing this speech and wondering: What, now, are you going to do? We don't want to hear about collecting data on inequality. The data is in the dead bodies. The data is in the decades of black voices crying out under billy clubs and bullets. The data is in the riots after another cop walks away from a murder, after another not-guilty verdict.

The real work is in rewriting policies of enforcement and training. Comey's platform and prominence demand that he make a real commitment to policy change. For the next photo-op at a comfy American university, have the police chiefs of America's 20 largest cities stand behind the FBI director as he explains what they will enact over the next three years.

The speech Comey just gave needed to be made, ideally, 30 years ago. It was a start. Let's reserve placing laurels on Comey's brow until he commits to real change: Understanding only goes so far; data collection and convening committees only does so much. Abstract sympathy has yet to stop a bullet.