Will fairy tales ever go out of fashion? This was the question E.L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey raised when it became an overnight success in 2012, and the question it will continue to inspire as diehard fans and potential converts flock to its big-screen adaptation, which opens on Valentine’s Day. Of course, those feeling flummoxed by the book’s popularity—as well as the runaway sales of its two sequels—have had a difficult time getting past the aspects of the story that make it seem like an entirely different breed of bestseller. Yet the astonishing success the franchise has enjoyed seems, more than anything else, to be proof not of audiences’ and readers’ craving for salty new trends, but their hunger for the most familiar narrative of all—and their desire not for sexual experimentation, but for traditional family values.

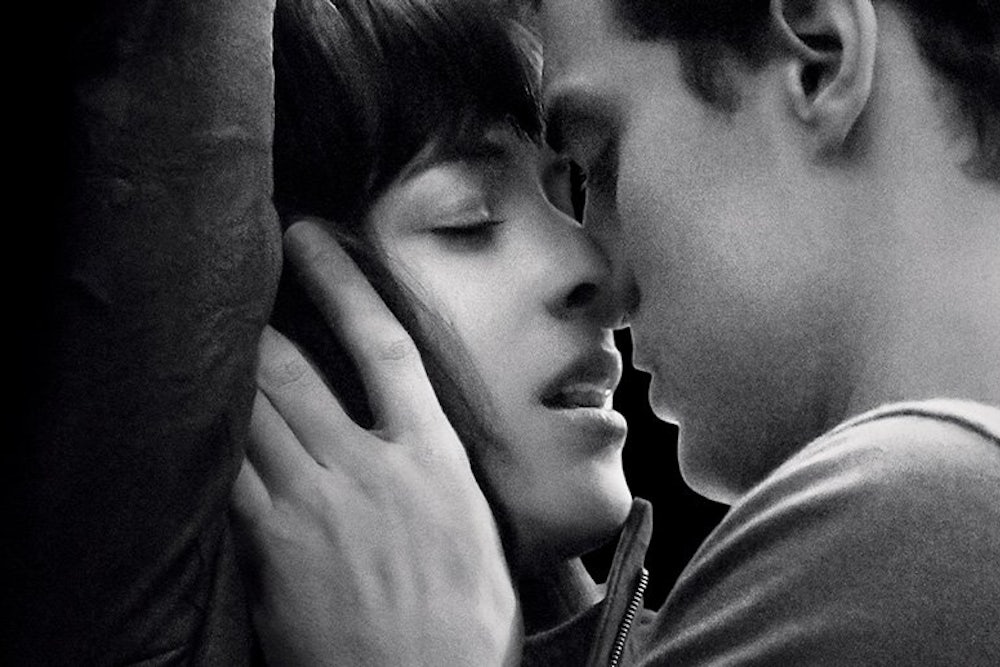

Both Fifty Shades of Grey and its hotly anticipated film adaptation tell the story of a master/slave relationship between charismatic business tycoon Christian Grey and unassuming college student Anastasia Steele, and both are heavily frosted with bondage and fetish-related plot points. Since the book’s first commercial publication, cover stories and editorials have sprung up as predictably as welts in the wake of a cat-o’-nine-tails, wondering how on earth such a nasty book could sell so well, or simply heralding a new era of “Mommy Porn” in the literary marketplace and bondage and sadomasochism in middle-class bedrooms—or at least on bedside tables. A fan of the series told Today show audiences that Fifty Shades of Grey was the first book she had read in nine years, while the New York Post gleefully reported a New Jersey housewife’s claim that “Kids have never seen their mothers reading so much,” and that Fifty Shades was known, simply, as “The Book.”

Fifty Shades of Grey began its brief and storied existence as a piece of Twilight fanfiction titled Master of the Universe, and published online in 2009 by a middle-aged Englishwoman named Erika Mitchell, whose nom de plume, Snowqueens Icedragon, seemed a better fit for a show dog or an heirloom tulip than a novelist. In 2010, Mitchell rechristened her fan versions of Edward Cullen and Bella Swann, hosted the result as a standalone novel on her own website, and renamed herself E.L. James. The book’s popularity grew through e-book sales and word-of-mouth, until finally emerging in the conventional literary marketplace in 2012. Within two years, the first book alone had sold 100 million copies, and become the fastest-selling paperback ever published in Britain, outstripping not just the Harry Potter series but the Twilight Saga—in other words, the very books that had inspired it.

It seemed to many E.L. James, America’s new softcore sweetheart, was working some kind of magic on jaded American consumers, and had stumbled on the one choice of subject matter that could get people reading again. Yet the roots of its popularity stretched much deeper than its author’s source material, and what a Newsweek cover storydubbed “The Fantasy Life of Working Women.” At its most basic, Fifty Shades of Grey—like Twilight, and like so many bestsellers that have come before—appealed not just to suburban housewives, but to the little girls they had once been. The story is less a booster for bondage (such as Pauline Réage’s legendary erotica, Story of O) than a retelling of Beauty and the Beast. At the end of her saga, when all the whips have been sheathed and the harnesses have been unstrung, Anastasia Steele has tamed and wedded her beast, given birth to one of his children, and conceived another. In its final lines, the narrative appears less a celebration of sexual transgression than of the nuclear family.

This moral is doubtless unwelcome news to anyone who has been waiting for mainstream Americans to embrace bondage, submission, and any other practices from the vast sexual rainbow that have been labeled “deviant.” Yet at least a few of the critics who welcomed Fifty Shades of Grey as a taboo-shattering blockbuster must have remembered making similar claims nearly 30 years ago, after the controversial release of Adrian Lyne’s Nine ½ Weeks. The movie, which met with critical drubbing and commercial disregard upon its theatrical debut in 1986, found a devoted following in the burgeoning home video market in much the same way that Fifty Shades of Grey found its readers via anonymous e-book purchases. Nine ½ Weeks told the story of a doomed romance between a John (Mickey Rourke), a handsome, charismatic, and emotionally unavailable businessman, and Elizabeth (Kim Basinger), a woman he enlisted as sexual and emotional submissive. (Sound familiar yet?) The movie, though scandalous in reputation, was light on paraphernalia: John’s props famously included ice cubes, Jell-O, and milk—the handcuffs were just for decoration.

In the end, however, Nine ½ Weeks was not a narrative of sexual experimentation and pleasure, and the pain it revealed to audiences was not physical, but emotional. John, the audience learned, played games of sexual and psychological dominance not because he was liberated, but because he was broken. The movie’s popularity was enough to inspire a generation of ever-more-daring erotic thrillers, but its most beloved revision came in the form of 1990s Pretty Woman, which, underneath its equally outrageous veneer, provided a happy ending to the fairy tale Nine ½ Weeks introduced. In this version, the handsome, charismatic, and emotionally unavailable businessman enlisted a woman as his sexual and emotional employee, and her love was strong enough to break the spell that had turned his heart to stone. In the final reel, the sex fell neatly by the wayside, yielding in favor of a narrative that held far more power over viewers’ minds.

In the past few decades, American media have both celebrated and mourned mainstream consumers' apparent acceptance of bondage and sadomasochism, in the form of commercial outings as diverse as Madonna’s Sex book (and her 1993 starring vehicle Body of Evidence), Garry Marshall’s Exit to Eden, and Steven Shainberg’s Secretary. In its most mainstream versions, however, BDSM has most often turned up as a means of making audience members feel amused, or revolted, or afraid. At its very best, as in Secretary, it has been pressed into service as a tool for showing viewers just how damaged two characters are, and how they experience sex not as pleasurable and fulfilling in its own right, but as a tool for healing. If the sex is truly doing its job, these movies tell us, then it is really just a crack through which the pure light of fairy tale romance can emerge—and so Secretary featured a handsome, charismatic, and emotionally unavailable businessman who … well, you know the rest.

Had more of the critics who tried to understand Fifty Shades of Grey’s success actually read the book before they began conducting ethnographies of Long Island housewives, they might have seen the series for what it was: a presentation of sexual boundary-crossing not as something to enjoy, but something to pathologize.

As Christian Grey pulls Anastasia Steele deeper into his “world” of sexual and emotional domination and control, Anastasia, the reader’s lens and placeholder, finds no great pleasure in the “punishment” Grey metes out to her, instead falling in love with the man himself, and focusing her efforts on the help she believes she can provide him. “This is a man in need,” she reflects in the first novel. “His fear is naked and obvious, but he’s lost … somewhere in his darkness. His eyes wide and bleak and tortured. I can soothe him. Join him briefly in the darkness and bring him into the light.”

Much of the first book centers on Anastasia’s confusion over whether she should agree to a contract Grey has drawn up, stipulating her duties as a submissive—“The Submissive shall not look directly into the eyes of the Dominant except when specifically instructed to do so. … The Submissive will not touch the Dominant without his express permission to do so”—but, like the decorative handcuffs and riding crop in Nine ½ Weeks, the contract itself never really comes into play. Grey and Anastasia engage in only the lightest forms of bondage, and each of these scenes is thickly larded with the least tremors of Anastasia’s growing love for the man she sees as her “courtly knight.” Anastasia offers readers their only vantage point, and, throughout, she sees not just bondage but all sexual intimacy primarily as a means to greater closeness with the man she loves—and eventually as a way to help heal his tortured psyche. “I do it for you, Christian,” she selflessly informs both her master and her reader, “because you need it. I don’t.”

Of course, by the end of the Fifty Shades saga, Anastasia’s selfless quest pays off in full: The beast, vanquished, has transformed into a prince, and she has become his princess. Movies that have explored bondage or—for that matter, any truly transgressive sexuality—as more than a means to an end have always been much harder to find than their fairy-tale-inflected offspring. Those promoting the film adaptation of Fifty Shades of Grey have made sure to promise that their movie will bust taboos. And maybe, just maybe, it will—I have not seen it yet. But viewers who find themselves in search of a more complicated view of sex and love this Valentine’s Day might still be better off staying home, and seeking out the stories of sexual exploitation that never achieved blockbuster status: movies, for example, like Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion or Lynne Stopkewich’s Kissed, or any of a hundred others that have fallen by the wayside because they have not adhered closely another to fantasy. Much as viewers who shell out for Fifty Shades may imagine themselves to be taking a gamble or slaking an indecent thirst, they may not be seeing anything more shocking than what they might find on any other screen in their neighborhood multiplex.