We can finally say it with certainty: The economic recovery is happening—and it keeps getting stronger. The economy added 257,000 jobs in January, the Labor Department reported Friday morning. The unemployment rate ticked up a notch, from 5.6 percent to 5.7 percent. But that’s actually good news because it resulted from more people entering the labor market. The labor force participation rate increased from 62.7 percent to 62.9 percent.

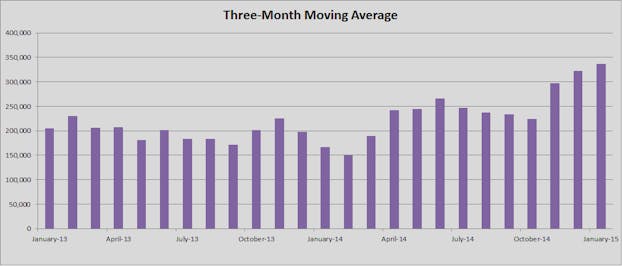

Even better, the November and December jobs numbers were revised up 147,000, a huge change. Job growth over the past three months has now averaged 336,000. Here’s the three-month moving average that shows just how a massive a surge that is:

But if you have been following job reports over the past year, you know that the headline jobs number is not the most meaningful data point. What we really have been looking for is wage growth—and that finally happened in January as well. The Labor Department reported that wages rose 0.5 percent in January. Over the past year, they’ve now increased by 2.2 percent. Those aren’t earth-shattering numbers by any means. But they are a sign that the wage story is finally turning around. Employees are finally gaining more leverage in the labor market to demand higher wages, and employers are having no choice but to give them to them.

There’s little not to like about this report. In fact, there’s little not to love about this report. As always, it’s important to take these numbers with a grain of salt. The Labor Department will revise them when it releases the February jobs report. Sometimes those revisions are significant. But it’s also clear that the economy is growing at a strong pace right now. And for the first time, we have hints that the recovery will do more than boost the pockets of big corporations. It looks like it might just help Main Street as well.

Whether that actually happens will depend significantly on the Federal Reserve. The Fed has kept short-term interest rates near zero since 2009 to encourage businesses to invest and consumers to buy houses and cars. But as the economy recovers, it will end that zero-interest-rate policy so as not to risk rising inflation. Most financial analysts expect that to happen later this year. That will be a pivotal moment for Fed chair Janet Yellen. Raise interest rates too soon and the Fed will stifle the recovery and prevent wage growth from reaching millions of Americans. Raise rates too late and moderate inflation could occur.

If you read those sentences and think that those risks are not the same, you’re right. “[T]the risks still seem hugely asymmetric,” New York Times’ columnist Paul Krugman wrote this week. “Raise rates ‘too late’, and inflation briefly overshoots the target. How bad is that? ... Raise rates too soon, on the other hand, and you risk falling into a deflationary trap that could take years, even decades, to exit.” A deflationary trap is when the economy gets stuck in a cycle of falling prices—deflation. Consumers don’t spend their money, expecting it to become more valuable in the future. Businesses don’t invest for the same reason. And debtors have more trouble paying off their debts. It’s a nasty cycle that leads to terrible economic conditions. Japan has been in a deflationary trap for nearly two decades now. Europe is right on the edge of entering one.

The United States isn’t likely to enter such a deflationary cycle. But it is a risk. Thanks to falling oil prices, headline inflation has fallen to 0.7 percent, as measured by Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). Core PCE, which excludes food and energy prices to reduce volatility, is 1.3 percent over the past year. Both of those are far below the Fed’s target of 2 percent.

Given that the recovery is just taking hold and there’s no inflationary pressure on the economy, it would make sense for the Fed to delay raising rates until we know that wages are actually, definitely growing, or until inflation moves much closer to the 2 percent target. Even if inflation rose above that 2 percent target for a while, that wouldn’t be the worst case scenario. After all, it’s a target, not a ceiling.

Meanwhile, there are other good reasons for the Fed to be cautious in raising rates. The Eurozone is teetering on the brink of another crisis after Greeks elected Syriza, the far-left party, to power with a mandate to renegotiate the strict conditions that the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund—known as the Troika—have set on its bailout. Earlier this week, the ECB fired a warning shot at both Greece and Germany, which has an outsized influence on the Troika, by cutting off Greek banks from a non-essential source of liquidity. If the Greeks and Germans cannot come to an agreement, Greek could end up leaving the European Union, potentially setting off renewed panic that would certainly have spillover effects in the United States.

At the same time, the ECB recently announced that it was implementing its own bond-buying program to try to help the Eurozone economies. That will weaken the euro and boost the dollar—hurting U.S. exports. Unrest in both Ukraine and the Middle East are also major causes for concern.

All in all, the January jobs report was very encouraging. The economic recovery is finally here. But there are many downside risks in the world that should concern the Fed and make them cautious in raising rates. As Charles Evans, the president of the Chicago Fed, said in September, patience is key.