Last week the World Health Organization reported that Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone—the three countries struck hardest by the Ebola outbreak— had hit fewer than 100 new cases a week, the lowest rate of new cases since June 2014. And in Liberia, trials of antiviral drugs have been halted due to a lack of patients. By many accounts, it seems as if the epidemic that has killed nearly 9,000 people has finally begun to decline.

“If we care about this, we need to think about how to rebuild, how to prevent it again from happening in future,” said Karen Grépin, an assistant professor of global health policy at New York University. “We’re going to have to start transitioning.”

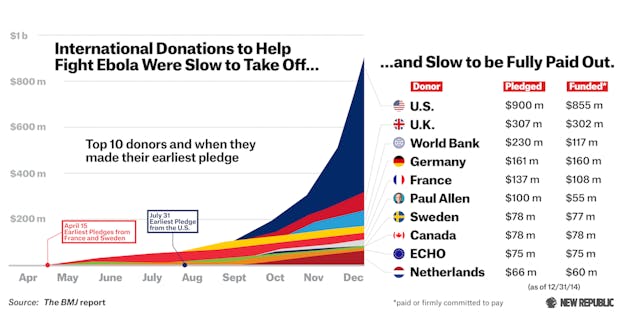

In a paper published online Tuesday in the British Medical Journal, Grépin reveals that of the $2.89 billion pledged by international governments, companies, foundations, and private donors towards the Ebola crisis, only about $1.09 billion—or around 40 percent of pledged donations—have been fully paid. The U.N. estimated last November that a total of at least $1.5 billion is needed to fully respond to the Ebola crisis.

The paper looked at international donations tracked by the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ financial tracking system. Through the tracking system, Grépin was able to identify the total amount pledged by donors, the amount committed (usually meaning pledged and under contract), and the amount paid in full. The study did not take into account some forms of aid, such as foreign medical teams, domestic resources, or loans from the World Bank.

Grépin notes in the study that a main reason for the Ebola crisis was the sluggish emergency response, not a lack of generosity from international donors. Grépin said that if the response to Ebola had been quicker, and therefore disbursement of funds had come sooner to countries in need, perhaps the spread of Ebola could have been less extensive.

WHO was first alerted to an outbreak of Ebola in Guinea in late March, but it wasn’t until August that the Ebola crisis was declared a health emergency of international concern. “When things are spreading exponentially, these delays could have big consequences for health,” Grépin said.

Donations to the Ebola crisis, such as the ones tracked by the study, go to an array of resources, such as personal protective equipment used in clinical care, food supplies, and hiring medical personnel, Grépin said.

The estimated $1.5 billion needed to contain the Ebola outbreak also doesn’t take into account long-term costs, such as ensuring that local health systems are sustainable once foreign aid organizations leave, Grépin said. The study found that only 11.5 percent of resources went directly to governments in affected countries to fight the epidemic. The majority of resources were donated to UN agencies (42 percent) and NGOs (18.9 percent).

In the wake of the Ebola crisis, Grépin recommends the creation of an emergency resources fund, which could be deployed rapidly to future global health threats. The week before Grépin’s paper was published, the board of the WHO announced it would create such a fund.

But Grépin said donors shouldn't assume that everything is fine now in West Africa. “As long as there’s one case still out there, the epidemic is still going.”