In March of 1903, a single woman in her late thirties walked into the U.S. Patent Office to secure her claim to a board game she had been diligently designing in the hours she stole from her day job as a stenographer. Lizzie Magie was an exception to the female norms of the time, not just because she had remained unmarried well beyond the conventional marry-by date, but also because she was an avid supporter of the teachings of progressive politician and economist Henry George, an outspoken and influential tax reformer who advocated policies that would keep more money in the hands of the poor and working class.

The invention Magie wanted to patent, was, in fact, a kind of tribute to George: The Landlord’s Game was “a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences,” Magie explained in The Single Tax Review in 1902. She included two sets of rules: one in which the aim was to crush opponents through monopolies, and one in which the creation of wealth rewarded all. The moral was not exactly hidden. The Landlord’s Game, Magie believed, would help make the world a better place.

By January 1904, when less than 1 percent of all U.S. patents went to women, Magie had received approval for her game. Just a few years later, it was being manufactured for sale around the country, finding pockets of fans along the Eastern Seaboard. People weren’t passing along the game so much as the idea—creating boards of their own, and tweaking the names of streets and the rules of the game. The game was successful enough that in 1935 Parker Brothers paid Magie $500 for a revised patent. But just a year later, even though many people around the country were playing a variation of the original game, its name, its “anti-monopolist” rules, and Magie herself, had been largely forgotten.

The funny thing is, you’d probably find The Landlord’s Game eerily familiar. It includes money, deeds, railroads, properties, and the words “Go to Jail.” Landing on certain squares means paying fees, a full trip around the board lets you collect fake cash, and the player with the greatest riches in the end wins. You probably call this game Monopoly, and you probably never gave a thought to its origin story—you certainly didn’t suspect it was born of an impulse to alleviate poverty. It’s a nostalgic pursuit, a way to get the family together away from the demands of their smartphones—though of course, now there’s an app, not to mention an electronic banking edition introduced in 2006 that features debit cards instead of cash, and tokens including a Segway and a flat-screen TV.

In an increasingly digital culture, traditional board games can feel like antiques, what with their printed, two-dimensional boards and pieces you move with your flesh-bound fingertips. What could these static things possibly reveal to us that we don’t already know? Mary Pilon’s new book, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, is an argument for the board game as not only a subject of investigation, but also as a powerful cultural mirror in its own right.

Particularly in a time before the Internet, a game was a key currency of communication, a teaching tool, a grassroots piece of entertainment, a method by which people could relate to one another, and a living artifact upon which players left their imprints. Through the evolution of Monopoly, Pilon explores not only forgotten stories like Magie’s, but the economic and political shifts brought about by the stock market crash, World War II, and Watergate—revealing how these changes were eventually reflected in the game itself. The classic floppy-boot game piece, for instance, was a product of the Great Depression, when such down-and-out footwear was a common sight.

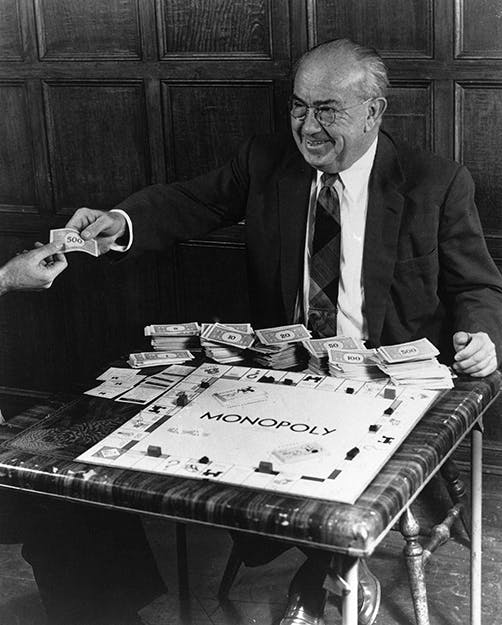

The man who ultimately received the credit for creating Monopoly is a Pennsylvanian named Charles Darrow, not an inventor, but an opportunist. An unemployed family man with an ailing child who was trying to survive in the midst of the Depression, Darrow was given a copy of the game by a friend, sneakily enlisted another pal to illustrate it (for free), and sold the reinvented product to a sinking Parker Brothers as his own (for $7,000 plus residuals), subsequently amassing a fortune. By 1936, the game had earned millions, saving not only Darrow, but also the company, from financial ruin. Darrow was given a place in history; his descendants continued to profit from the game for years after his death.

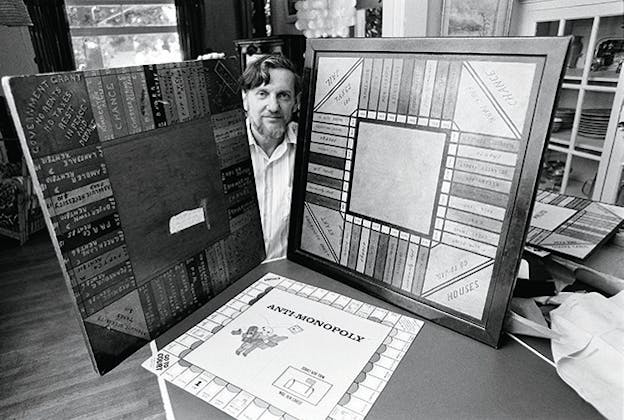

Later in the book, there is another compelling arc involving Ralph Anspach, the David to big-game’s Goliath, who takes on Parker Brothers so he can keep selling his game, Anti-Monopoly (a version that feels spiritually similar to Magie’s), in the Watergate-era 1970s. In trying to win his case, and keep the title of his game, Anspach, a San Francisco–based economics professor, tracked down Monopoly’s original players to prove that the game existed in the public domain long before Parker Brothers claimed Monopoly as their own.

It’s an immense task to explain the world we inhabit through the parameters of a board game and, at times, the sheer wealth of information seems to outpace Pilon’s narrative structure. Much of this material is genuinely entertaining, cocktail-banter nuggets of historical trivia: In World War II, Monopoly boards, by that point a symbol of capitalism and America, were used to conceal maps sent by the Allies to prisoners of war; “Marvin Gardens” was a misspelling of the Atlantic City housing development “Marven Gardens”—because that error was on the board Darrow sold to Parker Brothers, it became “one of the most repeated spelling errors in history,” writes Pilon. In the 1970s, an aggressive Parker Brothers barred two Cornell students from the world championship Monopoly tournament as punishment for writing their own rules to the game and publishing a book of strategy. There are broader lessons, too, on trademark law, on the his- tory of game development, on feminism in the 1900s, on the way corporations create brands and then try, sometimes brutally, to protect them. After Parker Brothers won an injunction against Anspach, the company buried 40,000 of his Anti-Monopoly games in a Minnesota landfill to make it “abundantly clear that it thought Ralph had no chance.”

But at times, the facts and characters in The Monopolists feel disparate, their only connection a tangential attachment to the board game. An entire book could, and should, be devoted to the amazing life of Lizzie Magie, for instance, but The Monopolists doesn’t try to do that. This limitation may be the inherent challenge of writing a book in which the lens is not a woman’s contribution to the world, but her contribution to a piece of cardboard. There is also no clear place for Pilon’s narrative to end, since the game is reinvented with each generation.

As a child growing up and playing Monopoly in the 1980s, I saw the game as an adult lesson in savvy dealings with money and entrepreneurship; it also hinted at a euphoria I suspected had something to do with becoming rich and powerful—or, in pretending that you were, if only for a moment. And yet, all along, there were stories in that board that I never suspected: the history of the trail-blazing woman who really invented the game; the tale of the man who got credit for it; and the copyright battle of the econ professor that went all the way to the Supreme Court. In the end, this is less a book about the impact of any single person than an analysis of the way an everyday object can adopt and reflect the values of various times.

One of the great ironies of Monopoly, of course, is that it was originally intended to be exactly the opposite of what it has become. And then there is another irony, as well: Monopoly came to be controlled by a company that fought tooth and nail to maintain its own monopoly over it. But part of the Monopoly story is surprisingly straightforward: Its path from progressive teaching tool to capitalist icon—with a mythology to spur it along as a money-making brand—makes it something of an American archetype of its own.