In June 1975, a Yale economist named William Nordhaus published a paper for the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, an Austrian think tank. In the paper, he put forward a theory about a potentially globe-altering climate-change Red Line—a threshold that, if crossed, could result in a fusillade of environmental dangers. Research suggested that a rise in carbon-dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels might melt the Arctic Sea ice, prompting a “dramatic” increase in rain and surface temperatures. “The consequences of these changes for human affairs are clouded in uncertainty,” he wrote, but the prudent response was clear: Prevent emissions from pushing the mean global temperature more than 2° Celsius above pre-Industrial-Age levels.

In 1990, a United Nations climate change advisory group transformed Nordhaus’s little-noticed notion into a global line in the sand. The two-degree shift “can be viewed as an upper limit beyond which the risks of grave damage to ecosystems are expected to increase rapidly,” the group wrote in a report. “Important scientific uncertainties remain,” it added, but they “must not be used as an excuse to avoid adopting policies” that would avoid breaking through the two-degree barrier. Since then, scientific research, reporting, and economic analyses have centered on this particular number.

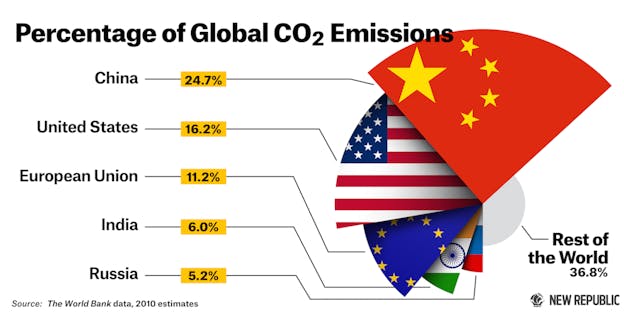

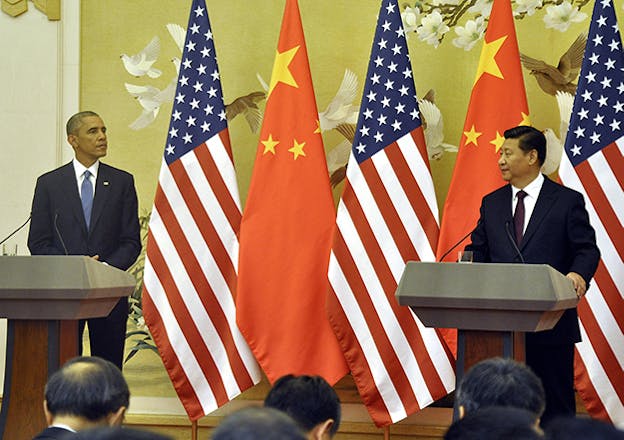

In November 2014, during a meeting in Beijing of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, President Barack Obama joined with Chinese President Xi Jinping to pledge their countries, the world’s two top carbon-dioxide emitters, to clear emission-reduction targets. Xi vowed that China’s rapidly expanding emissions would peak by approximately 2030; Obama committed the United States to cut its emissions at least 26 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. These cuts, Obama said, would help achieve the “deep emissions reductions by advanced economies” that the global scientific community has deemed necessary to prevent “the most catastrophic effects of climate change.”

Admirable goals, but they’re unlikely to have the intended effect. Even with these changes, scientists expect global temperatures to breach the two-degree barrier within the next 20 to 30 years. Last year, a report by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said that temperatures are “more likely than not” to exceed 4° Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100.

Keeping temperatures within the two-degree window remains possible, but it won’t be easy. It would require slashing man-made greenhouse gas emissions as much as 70 percent below 2010 levels by 2050, according to the IPCC—and then essentially eliminating them altogether by 2100. That is a radically different path than the one the world has chosen. Emissions today, despite impassioned calls by environmentalists, celebrities, and the right-minded, are headed in the same direction as when Nordhaus introduced the two-degree barrier 40 years ago: upward.

Climate change is the hardest of all environmental problems. Its chief cause, carbon dioxide, is invisible, and its deleterious effects play out over decades, thus minimizing the public sense of crisis. It is largely produced by burning fossil fuel—which is to say by doing almost anything. And a meaningful solution would require life-changing action by the largest economies on earth. Little wonder that political inertia has prevailed.

The fossil fuel industry has lobbied hard against climate legislation, correctly seeing it as a threat to profits from coal, oil, and natural gas. Leading Republican legislators continue to dispute that a problem even exists. On January 21, 49 senators, all Republican, voted against a relatively anodyne nonbinding resolution that stated that humans contribute to climate change. In 2012, Oklahoma Republican Senator James Inhofe, chair of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, published a climate change book titled, The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future.

Key Democratic politicians have professed support for a climate crackdown in theory, but they’ve sprinted headlong from it when confronted with the details of the cost to companies and voters in their districts. West Virginia Democratic Senator Jay Rockefeller is a good example. In 1972, when he ran for the state’s governorship, he campaigned against strip-mining for coal, a stance he described in a subsequent Time interview as having “adrenalized” him. In 2003, he voted for a bipartisan cap-and-trade bill limiting carbon emissions. (The bill was defeated.) In 2010, though, with Democrats in control of the Senate, the House approved a climate bill and Rockefeller declined to use his leadership position to pass it.

In China, meanwhile, government planners have been predicting for five years that the country’s emissions will peak around 2030. That’s partly due to China’s slowing growth and is also a by-product of its campaign to mitigate smog. It does cast Xi’s pledge in a decidedly less revolutionary light, however. So does the near certainty that his proposed cuts will not stop the planet from passing the two-degree threshold.

Something has to change. Partisan fighting on either side of the aisle won’t do it. Neither will international climate agreements, which have been easily gamed. A technological breakthrough—a clean-energy silver bullet that would allow the world to decouple economic growth from carbon dioxide—might. But betting on a grand laboratory innovation requires hope for the best; better to hedge against the worst. The means to meaningful change on global warming is within the world’s grasp. It requires smarter climate policy: more targeted and more economically efficient. It requires, in short, getting more realistic.

The Keystone XL pipeline has in recent years become America’s Big Green Bogeyman, a totem for the nation’s collective environmental fears. But it isn’t clear why. Environmental activists note, correctly, that heavy oil from Canadian sands is particularly carbon-intensive to produce. But many also pretend that if the giant tube didn’t run through the United States, the oil would stay in the ground. The reality is that Canada would almost certainly still produce the oil. It simply would sell it to someone else.

Keystone XL was proposed in 2008. Initially, opposition to it was limited mostly to people who lived along its planned route. In June 2011, however, it burst into mainstream attention with the publication of an open letter signed by 11 U.S. and Canadian scientists and environmentalists, including James Hansen, an influential former NASA scientist; Bill McKibben, the journalist turned climate campaigner; and Danny Glover, the actor. The letter advocated civil disobedience to stop the pipeline, calling Keystone XL “a fifteen-hundred-mile fuse to the biggest carbon bomb on the planet, a way to make it easier and faster to trigger the final overheating of our planet.”

Over the next several weeks, hundreds of people were arrested at the White House during anti-pipeline protests. On November 6, an estimated 12,000 environmentalists formed a circle around the White House in protest. National press flocked to the incidents and the issue. Days later, Obama announced that the proposed pipeline would undergo further analysis. In June 2013, as the State Department was conducting an environmental review of the project, which it was legally required to do, Obama announced that he would approve Keystone only if it “does not significantly exacerbate the climate problem.” Environmentalists were elated. By the president’s standard, McKibben wrote in a blog post that October, killing the project was “as close to a no-brainer as you can get.”

The State Department disagreed. In January 2014, its environmental assessment deemed Keystone XL “unlikely to significantly impact the rate of extraction in the oil sands”; it would likewise do little to reduce “the continued demand for heavy crude oil at refineries in the United States.” With or without the Keystone XL, the world would burn the oil and emit greenhouse gases. The pipeline, in that sense, was carbon-neutral.

Environmental activists have always known that Keystone XL’s significance is largely symbolic. “When we’re able to focus on distinct, concrete projects, we tend to win,” Michael Brune, the executive director of the Sierra Club, told The New York Times in January 2014. “And when we tend to focus on more obscure policies or places where we need action from Congress, we tend to stall, like every other thing tends to stall.” The government’s conclusion about the climate reality of the pipeline, in light of Brune’s analysis, raises the question of what constitutes an environmental “win.”

Keystone XL is a glaring example of the problem with the world’s continuing reliance on polluting fuels. But the resources arrayed against it make little sense. If global demand for the fuel exists, the fuel will be supplied. To keep oil in the ground, the best strategy—a real strategy—is to forgo political theater and empty victories. Instead, the government should create policy that makes dirty oil more expensive and cleaner energy cheaper.

Here’s a climate priority worth fighting for: renewable power, particularly energy from the wind and sun. Low-carbon energy projects have proliferated around the world in recent years, largely due to a surge in government subsidies. More public money has meant more research and more manufacturing, which has in turn driven the price of wind turbines and solar panels down. Subsidizing renewable energy makes good environmental and economic sense. What doesn’t make sense is how wastefully the United States does it.

In the 1990s, generous government subsidies in Japan and Germany created a solar-power industry. Panels began to appear on the rooftops of homes and offices in Tokyo and Berlin. In 2005, as oil prices surged, U.S. politicians decided the time had come to develop a solar industry in America, too. Congress introduced a juicy subsidy: a tax credit that allowed owners of new residential or commercial solar power systems to deduct 30 percent of the installation costs from their federal income taxes.

The problem is that Congress pegged the incentive to the expense of a solar project, not to how much clean electricity it produces. The credit provides a financial benefit to businesses. But it creates no incentives to develop better solar panels. The tax credit will phase out starting at the end of 2016 and expire altogether in 2018. The solar industry is lobbying to preserve it and to discredit its proposed replacement. In early 2014, the Obama administration suggested replacing the expiring investment credit with a permanent one for production—one likelier to be less generous to solar. Predictably, the Solar Energy Industries Association announced that the move would have “devastating consequences on the future development of solar energy in America.”

Ultimately, these credits, which primarily benefit companies and individuals with taxable incomes large enough for them to hold significant value, are an inefficient method to subsidize new forms of energy. The credit system has created an industry of financial middlemen who profit by selling tax liability in exchange for helping smaller renewables producers take advantage of the credits. The middlemen include Wall Street banks, as well as publicly traded companies that lease rooftops, install panels, and sell the resulting power back to the residents or businesses. One renewable-energy trade group has estimated that 30 percent of the money U.S. taxpayers spend on renewable-power tax credits goes to financiers rather than to renewable energy production. A smarter strategy would be to provide solar support through alternative incentive structures that are open to a broader group of players.

U.S. politicians have also stymied climate policy by yoking it to American-jobs boosterism. If the United States were serious about curbing carbon emissions, it would be willing to cede some clean-energy-factory jobs to countries that can make certain clean-energy products more cheaply—countries such as China.

Examples of how this kind of nationalism can go wrong abound. In 2009, as part of the recession-era stimulus plan, the government awarded solar-panel maker Solyndra a $535 million loan guarantee to build highly efficient solar panels. Solyndra took the money and went bankrupt two years later, sparking an immediate outcry, particularly from Republicans, who viewed it as proof that renewable energy was a charade. In fact, Solyndra was simply a bad investment. For one thing, its technology was innovative but not ready for large-scale production. In addition, as Solyndra was trying to ramp up production with taxpayer cash, a bevy of Chinese solar-panel companies, aided by subsidies from their government, quickly came to dominate the global market with less-innovative, but also less-expensive, panels. The Chinese companies forced down consumer prices, helping to drive Solyndra from the market.

At the same time that Solyndra received its loan guarantee, Fisker Automotive, maker of the Karma, a $100,000 luxury hybrid-electric car, was approved for its own $528 million in loans. A123, a Massachusetts company that made batteries for the Karma, also received $249 million from a separate federal fund. Both Fisker and A123 soon ran into trouble. In 2011, a problem with hose clamps attached to the Karma’s batteries forced Fisker to recall 239 cars. The following March, a Karma failed during a Consumer Reports test, prompting A123 to issue a larger battery recall. The federal government froze its payments to Fisker after having given the company less than $200,000.

In August 2012, a Chinese auto-parts maker, Wanxiang Group, offered to pay $465 million to buy approximately 80 percent of A123. But U.S. lawmakers objected to selling American technology to China, particularly technology that U.S. taxpayer money helped develop. A123 filed for bankruptcy, and in December 2012 its assets were auctioned. The winner: Wanxiang, which paid $257 million for the bankrupt version of an American company that, just four months earlier, it had offered to buy for nearly twice the price. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a federal panel, approved the sale. Fisker, too, declared bankruptcy, and in February 2014 its assets, too, were bought by Wanxiang, for $149 million.

A month after Solyndra filed for bankruptcy in late 2011, SolarWorld Industries America Inc., a U.S. subsidiary of a German solar-panel maker, filed a complaint with the Commerce Department. It alleged that the Chinese solar-panel industry was violating international trade rules by “dumping” its panels—selling them for less than the production cost. SolarWorld also charged that the Chinese government’s subsidization of China’s solar industry was significant enough to be considered a violation of international trade rules. The company called on the U.S. to retaliate with tariffs to protect domestic solar-panel makers.

The Commerce Department agreed, imposing tariffs on imported Chinese panels in 2012 and ratcheting them up over time. The combined impact of those tariffs, in some cases, represent a surcharge of more than 100 percent on the price of panels from Chinese solar firms. A costly irony is at play here. With one hand, Washington uses the investment tax credit as a subsidy to make solar power cheaper. With the other, it slaps tariffs on imported Chinese panels, making solar power more expensive.

The United States should support a domestic clean-energy industry, subsidizing deserving companies and protecting them when necessary. But it should be strategic about it and not get lost in “Made in the U.S.A.” mythology. It’s noteworthy that Solyndra and Fisker were both manufacturers. Obama’s loan program has suffered no losses in the far larger pool of loans it has made to projects that produce actual clean energy: solar farms, wind parks, and the like. Those projects often use equipment made by foreign companies.

The United States won’t win every leg of the clean-energy race. Maximizing employment in U.S. factories that make renewable-energy equipment—generating, as the politicians like to say, “green jobs”—makes sense as part of a climate strategy. But only when it can be done without throwing good money at bad companies. And only while minimizing tariffs that raise the price of low-carbon energy.

In December, diplomats from around the world will gather in Paris for the twenty-first annual United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change conference. These are massive, and typically ineffectual, affairs. Thousands of diplomats, environmental campaigners, business lobbyists, and reporters descend on a conference hall in some world city. Little happens until the last day or so, when the diplomats get serious and pull an all-nighter. Exhausted voices rise to debate which countries should have to pay how much for the climate cleanup. Around dawn, the dignitaries crank out a concluding text that falls far short of action relevant to the two-degree goal.

Paris is being billed as a crucial stop on the road to a comprehensive global effort to stanch climate change. The existing climate-change treaty, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, will effectively expire in 2020. When it was negotiated, it was hailed as ushering in an era of deep emission cuts. Al Gore, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for his campaign against climate change, was one of its chief supporters. But the Kyoto treaty hasn’t provided anything like what its architects predicted. From the start, it was fundamentally flawed.

The treaty obligated the world’s developed nations to cut emissions by a cumulative 5 percent below 1990 levels by 2012. Two key features eroded its environmental effect.

First, it didn’t compel reductions from countries whose emissions were rising the fastest: developing nations, particularly China and India. The industrialization of the developed nations had created the crisis, went the reasoning; those countries should initiate the global transition to a cleaner energy system. Even before the agreement was concluded, however, the U.S. Senate made clear it wouldn’t ratify the treaty. The Senate voted 95-0 in a nonbinding resolution that it disapproved of any treaty that didn’t force emission cuts from developing countries and that “would result in serious harm to the economy of the United States.”

The second problem with Kyoto stemmed from a structural feature that at the time seemed a stroke of geopolitical and economic genius: a system in which carbon emitters around the planet could produce, and then buy and sell, government-sanctioned permits to pollute, better known as “cap-and-trade.”

Suppose a company in China builds a solar-power farm. The farm indirectly cuts carbon because it displaces China’s need for coal-fired electricity. Under Kyoto, the company calculates the number of tons of carbon-dioxide emissions its project will offset; then it takes that calculation to U.N.-deputized carbon regulators, who review the request and issue a number of so-called carbon credits, each representing one ton of carbon dioxide not sent into the air. The company in Beijing can then sell those credits to a company in a Western country—say, Germany—that is obligated, under Kyoto, to reduce emissions. A market is made, the developing countries are induced to clean up their acts, and the climate cools.

That was the theory, but the reality has proved otherwise. The global carbon market—worth $63 billion last year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance—has been gamed in two ways. First, corporate lobbyists persuaded politicians in many countries to weaken national carbon-reduction mandates. Second, the officials deputized by the United Nations to determine the legitimacy of a project’s carbon reduction approved a host of projects that simply weren’t. Some were from projects that the companies were going to build anyway. Some were for projects that, even if they did curb carbon emissions, perpetuated or exacerbated other ecological ills. For example, carbon credits helped finance the creation of large tree plantations in some developing countries. Trees are good: They benefit the atmosphere because trees consume carbon dioxide as they grow. But to establish such plantations in those countries, growers destroyed habitats that previously contained diverse plant and animal life.

Another approach is needed. Instead of cap-and-trade, the United States should impose a carbon tax. The tax could be structured so that it is revenue-neutral—a phrase much-beloved by politicians—and returns the carbon proceeds to the American people by cutting other taxes, such as those on income, which fiscal conservatives contend are a bigger drag on the economy. For years economists have called for a carbon tax, and for years politicians have dismissed the idea as a nonstarter. But a pivotal moment is approaching in Washington, one in which overarching tax reform actually might take place. Such a moment could provide political cover for this tax, because it would be part of a larger political bargain. Democratic environmentalists would get a stick with which to cajole (or worse) emitters to cut carbon; Republican fiscal conservatives would get the carrot of rolling back income taxes and other levies that they believe stymie growth.

A world in which the mean global temperature stayed within the two-degree threshold would be different in almost every respect from the one that presently exists. It would require eating, traveling, trading, and manufacturing in palpably new (but hopefully not archaic) ways. Humanity has solved a multitude of localized environmental problems: dirty water, dirty air, dirty soil. It even has addressed some global ones, most notably the ozone hole. But it never has solved an environmental problem as complicated as climate change.

The measures proposed thus far by the United States, China, and other countries in the lead-up to the Paris climate conference will not prevent the planet from breaking through the two-degree threshold. They do suggest, however, that competing global players can fashion climate strategies if they see them as serving, rather than eroding, their own economic interests. The test now will be whether that shift toward geopolitical realism can usher in environmentally meaningful action.

It is exactly what the fight against global warming needs. In the United States, too many conservatives have ignored environmental reality, discounting the mounting science; and too many liberals have ignored economic reality, larding on inefficient support. Both approaches are irresponsible and must be discarded.

Unless an astounding number of scientists across a multitude of disciplines are stupendously wrong, man-made climate change is no hoax. But if it’s as serious as they say, it requires a serious response. Serious doesn’t mean loud and grandiose. It means robust for the environment and feasible for policymakers across the political spectrum. One without the other is just cheap ideology. Here’s the real inconvenient truth: Global warming won’t be solved by political hot air.