By his sophomore year at Brown University, Lex Rofes knew he wanted to pursue a career in Judaism. Whether as a rabbi or a teacher, he was committed to working in the service of American Jewry.

So when a recruiter from a rabbinical college came to speak in his junior year, Rofes made sure he was in attendance. “I was certainly thinking of it as a real option,” he said.

That is, until a friend raised her hand and inquired about the school’s policy on interfaith relationships.

“I sort of went pale,” recalled Rofes, who was dating someone outside of the religion.

Nearly all of the country’s rabbinical colleges have firm policies that prohibit the admission and ordination of students who are in committed relationships with non-Jewish partners. Even as interfaith couples are increasingly being welcomed into congregations of all denominations, they are effectively barred from pursuing the rabbinate.

By the end of this year, that could all change. The Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, which ordains rabbis for the denomination’s more than 100 congregations across the country, took the first step late last year toward ending the policy prohibiting applications from students in interfaith relationships. Faculty at the college, located just outside of Philadelphia, cast a preliminary vote in November to reconsider their admissions standards, though college officials are quick to note that the vote only signifies that they are taking the matter under serious consideration, not that the final decision is a fait accompli.

In the interim, leaders from the college are soliciting feedback from Reconstructionist Jews around the country—and they're getting it, sometimes loudly.

At congregational meetings and in online forums, opponents are taking aim at the proposal and at the RRC for even considering it. To some, the proposal is just a way for the college to pad its dwindling applicant pool. Others fear that it would lower expectations for their religious leaders. While the rhetoric almost always remains civil, it does occasionally lurch towards the hysterical, like one commenter who, during a previous debate on the subject, equated the inclusion of interfaith rabbis to the work of the Nazis.

“What Hitler couldn’t do to the Jewish people we are doing to ourselves through the dark side of acculturation—intermarriage,” the commenter wrote. “To even suggest that it is ok for rabbis to marry non-jews is to put the final nail in the coffin of removing such liberal groups from any semblance of connection to the religion of our ancestors.”

Reconstructionist Judaism grew out of the work of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan in the middle of the last century as an offshoot of the more traditionally religious Conservative denomination. Though level of observance can vary from congregation to congregation, the movement fundamentally rejects the belief that Jewish law is unimpeachable, and embraces the concept of Judaism as both a religion and a community of people bound by culture and ancestry.

In practice, this has led to some of the most progressive and controversial reforms in Judaism. Reconstructionists have shepherded the rest of the religion into the twenty-first century, ordaining female and gay rabbis, officiating same-sex weddings, and embracing interfaith congregants before any other denomination. Each of those decisions has been met with similar derision from Judaism’s more orthodox gatekeepers.

Supporters of the proposed policy change on interfaith relationships argue that it's in keeping with the progressive values that the movement is built upon. But for opponents of the measure, the issue isn’t so much a matter of upholding progressive ideals as it is ensuring one of Judaism’s central tenets isn’t completely erased from practice: the notion of a Jewish “peoplehood,” communities that are bound by common ancestry and cultural upbringings, in addition to religious belief.

“We have always welcomed change when we felt it strengthened our religious peoplehood or when we understood there to be an ethical imperative to do so,” said Rabbi Lester Bronstein of Bet Am Shalom in New York, the congregation where—full disclosure—I grew up and celebrated my Bar Mitzvah. “Likewise, we have avoided change when we believed it to be detrimental to that fundamental cause: the creation and furthering of ethical religious peoplehood.”

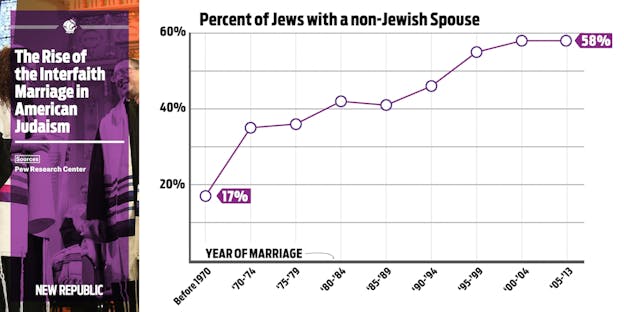

There is plenty of data to support opponents’ concerns. The rate of interfaith marriage in Judaism has grown rapidly in the last half-century, from just 17 percent in 1970 to nearly 60 percent today, according to a recent study from the Pew Research Center. And among Jews with non-Jewish spouses, only 20 percent say they are raising their children to be Jewish, compared to 96 percent of families with two Jewish parents. To ordain interfaith rabbis, some argue, is to tacitly endorse interfaith relationships, which have contributed to a dwindling population that identifies as religiously Jewish.

The Reconstructionist Rabbinical College was set to make a final decision on the policy next month, in time to affect the next admissions cycle in the fall. But the debate over the policy prompted the RCC to delay the vote until September. In a written statement to The New Republic, Josh Peskin, RRC's vice president of strategic advancement, explained why they're contemplating a change.

“While statistics show that many inter-partnered Jews are not strongly affiliated with Jewish communities, it is also now clear that intermarriage is not necessarily a barrier to robust participation in and leadership of Jewish communities. Within our more than 100 Reconstructionist congregations, we have clearly witnessed first-hand that inter-partnered Jews can be committed, inspiring and effective Jewish leaders.”

Other large rabbinical schools have openly discussed ending their non-Jewish partner policies over the years, but few have actually followed through. Hebrew Union College, which is affiliated with the Reform movement, decided to keep their policy after much deliberation in 2013.

Last month, students on the board of the United Synagogue Youth, the youth group affiliated with the Conservative movement, voted to lift the group’s ban on interfaith dating. That's a fairly radical step for a denomination that still prohibits rabbis from officiating interfaith marriages.

Interfaith marriage is not strictly a Jewish quandary. From 2000 to 2010, nearly half of all marriages in the United States were between couples of different faiths, a figure that has more than doubled since the 1960s. But Jews are the most likely to marry outside their religion.

Supporters of the policy change say that’s exactly why it’s time to welcome interfaith rabbis. With some congregations reporting more than half of their members as being in interfaith partnerships, having a rabbi who is also in an interfaith relationship could provide a powerful role model for couples who are unsure of how to square their own relationships with a desire to raise a Jewish family.

Rabbi Mychal Copeland, the director of InterfaithFamily in the Bay Area, graduated from RRC in 2000, but only after her partner—whom Copeland met while she was studying for her PhD in Early Christianity at Princeton—agreed to convert.

“This is for me the single most important reason for supporting a change,” she said. “Especially in the work that I’m doing now, working with young couples. I’m actually able to be a model for people who don’t have models."

While the RRC does not admit or graduate students who are partnered with a non-Jew, there is no policy banning students from interfaith relationships while enrolled. Still, Copeland said there were times when her relationship felt burdensome. “Sometimes we were a little closeted, which was ironic because we had just come out as lesbians.”

Rofes, like many others, is hesitant to equate the push for interfaith acceptance to similar campaigns to accept Jewish women and gays. After all, interfaith marriage is a choice. But the absence of any nuance in the policy—it offers no wiggle room to applicants who display otherwise exemplary credentials but are dating outside of Judaism—is problematic for many people.

“The fact that it is a veto is, to me, really frustrating,” said Rofes, who has been in an interfaith relationship for the last three years. “It’s a statement about the nature of a person, that no matter what they do, no matter the depth of their knowledge, no matter the content of their character, that they are not qualified. And that to me is a form of prejudice.”

Update (10/1/2015):

On September 30, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College announced that it has formally lifted its ban on students who are in committed interfaith relationships.

“Today’s announcement is a decision by our faculty about what should or should not hold someone back from becoming a rabbi," said RRC President Rabbi Deborah Waxman in a statement. "Our deliberations, heavily influenced through consultation with alumni, congregations and students, have simultaneously led us to reaffirm that all rabbinical candidates must model commitment to Judaism in their communal, personal, and family lives. We witness Jews with non-Jewish partners demonstrating these commitments every day in many Jewish communities."

The announcement also marks a first for American Judaism. No other rabbinical college currently admits or graduates any student who is in a committed relationship with a non-Jewish partner, even as similar bans have fallen for female and LGBT students.