On Thursday, the government filed its brief to the Supreme Court in the case that will determine whether Obamacare subsidies disappear in three dozen states. Its argument is comprehensive, but one part of it speaks directly to the political history of the law, and the fact that everybody, including Republicans in Congress who now claim out of convenience that the law plainly limits subsidies to states that set up their own exchanges, always understood it to authorize subsidies everywhere.

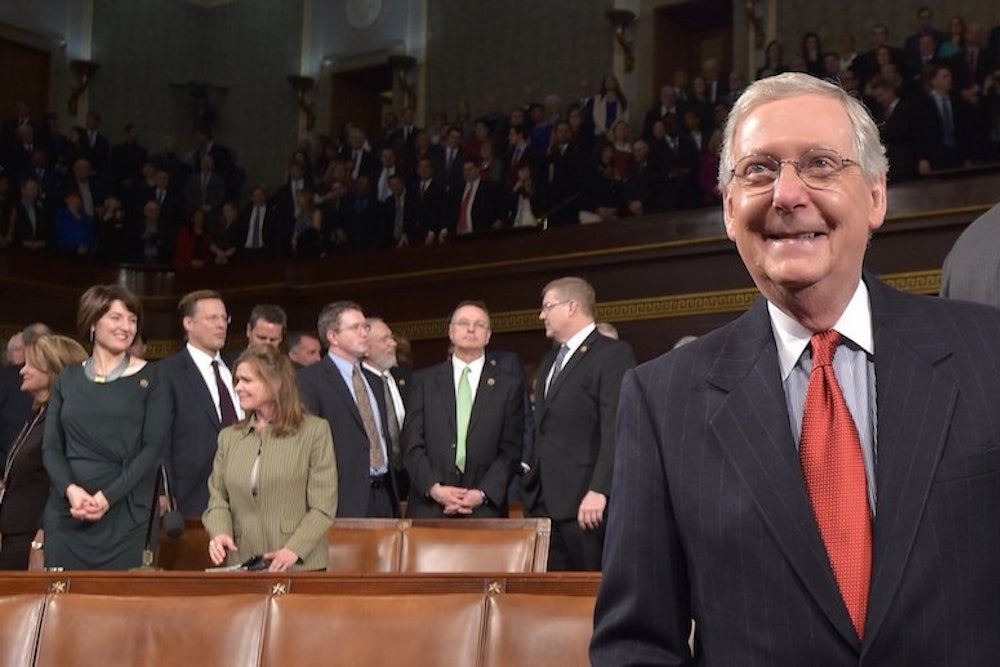

The government confines this part of its argument to the legislative debate in the run up to the law’s passage in early 2010, but it could make the point more succinctly (and perhaps convincingly) by fast forwarding to early 2011. These days, Republicans up to and including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell confidently pronounce that “the language of the law says … subsidies are only available for states that set up state exchanges.” But that’s not what they believed four years ago.

When Republicans took over the House in 2011, the political environment in Congress changed dramatically. Obamacare couldn’t be repealed, but it became fair game for damaging modifications, and the GOP took aim at it and other domestic spending programs whenever opportunities to offset the cost of new legislation arose. One of the first things Congress did back then was eliminate an Affordable Care Act provision that would have significantly expanded the number of expenses businesses are required to report to the IRS. Even before the law passed, business associations were livid about the “1099” requirement, and created such an uproar over it that the question quickly became how, not if, it would be repealed. Even Democrats wanted it gone.

The only problem was that the reporting requirement was expected to raise over $20 billion. Under GOP rule, it could only be offset with spending cuts elsewhere in the budget. As it happens, they found those spending cuts elsewhere in the ACA itself. Specifically, Republicans paid for repealing the 1099 provision by subjecting ACA beneficiaries to stricter rules regarding when they have to reimburse the government for subsidy overpayments. Make more money than you anticipated, and the government will claw back your premium assistance come tax season.

The congressional budget office scored the plan as essentially deficit neutral, and Republicans voted for it overwhelmingly. But you see the problem here. If the ACA plainly prohibits subsidies in states that didn’t set up their own exchanges, then there would be no subsidies in those states to claw back. And by April 2011, when the clawback passed, we already knew that multiple states were planning to protest ACA implementation and let the federal government set up their exchanges, including giant states like Florida, which now has a million beneficiaries. They would have needed a different, or additional, pay-for.

Obamacare’s legal challengers might chime in here to insist that their case is impervious to revelations like these. CBO’s analyses were premised on the idea that every state would set up its own exchange, and Republicans (and many Democrats) based their votes on what CBO told them. Other Democrats who actually understood the scheme may have simply pretended not to notice the problem. Nevertheless, they’d say, the law was designed to withhold subsidies from people whose states didn’t establish exchanges, and to ruin the individual and small-group insurance markets in those states, without providing any notice to either. In a perverse way, the absurdity of the challengers’ argument is it’s greatest strength. Because the scheme they insist Congress intentionally created was so far from Congress’ mind, it’s hard to find contemporaneous evidence that Congress absolutely didn’t mean to condition these subsidies. In much the same way, we can’t be sure that Congress didn’t mean to denominate those subsidies in Canadian dollars. A $ isn’t necessarily a $ after all.

But this familiar line of defense crumbles here. It is facially plausible—though incorrect—to posit that at the time the law passed, CBO believed subsidies would be available everywhere because it simply assumed every state would set up an exchange. But that assumption didn't hold in April 2011. Something else must explain CBO's 1099-repeal score, and the Republican votes that followed it. What we have in the form of this bill is clear evidence that everyone who voted for it (including every single Republican, save the two GOP congressmen and one GOP senator who weren’t present) understood the Affordable Care Act to provide subsidies everywhere.

Congress repealed the 1099 provision at an important moment—after multiple states announced that they would step back and let the federal government establish their exchanges, but before the IRS issued its proposed rule stipulating that subsidies would be available on both exchanges. The only thing Congress had to go on when it stiffened the clawback mechanism was its own reading of the Affordable Care Act, and Congress behaved exactly as you would expect. It operated with the understanding that subsidies were universal.

Today, many Republicans will tell you that the law plainly forecloses subsidies through the federal exchange. Six senators—John Cornyn, Ted Cruz, Orrin Hatch, Mike Lee, Rob Portman, and Marco Rubio—and nine congressmen—Marsha Blackburn, Dave Camp, Randy Hultgren, Darrell Issa, Pete Olson, Joe Pitts, Pete Roskam, Paul Ryan and Fred Upton—have even filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court, which begins, “The plain text of the ACA reflects a specific choice by Congress to make health insurance premium subsidies available only to those who purchase insurance from 'an Exchange established by the State….' The IRS flouted this unambiguous statutory limitation, promulgating regulations that make subsidies available for insurance purchased not only through exchanges established by the States but also through exchanges established by the federal government.”

All of them, save Cruz, who was elected in 2012, voted for 1099 repeal.

In its brief, the government argues that “it was well understood that the Act gave ‘States the choice to participate in the exchanges themselves or, if they do not choose to do so, to allow the Federal Government to set up the exchanges.’ And it was abundantly clear that some States would not establish their own Exchanges.“ It was more than well understood. Congress actually endorsed that very proposition.