It took one day for the party of climate change denial to rediscover science—a few of them, anyway. Mitt Romney, who is considering his third presidential run, told a Utah audience, “I’m one of those Republicans who thinks we are getting warmer and that we contribute to that,” arguing for “real leadership” to tackle rising carbon pollution. Then, 15 Republican senators voted in favor of a conservative climate amendment that said "human activity contributes to climate change." One of those senators was Rand Paul.

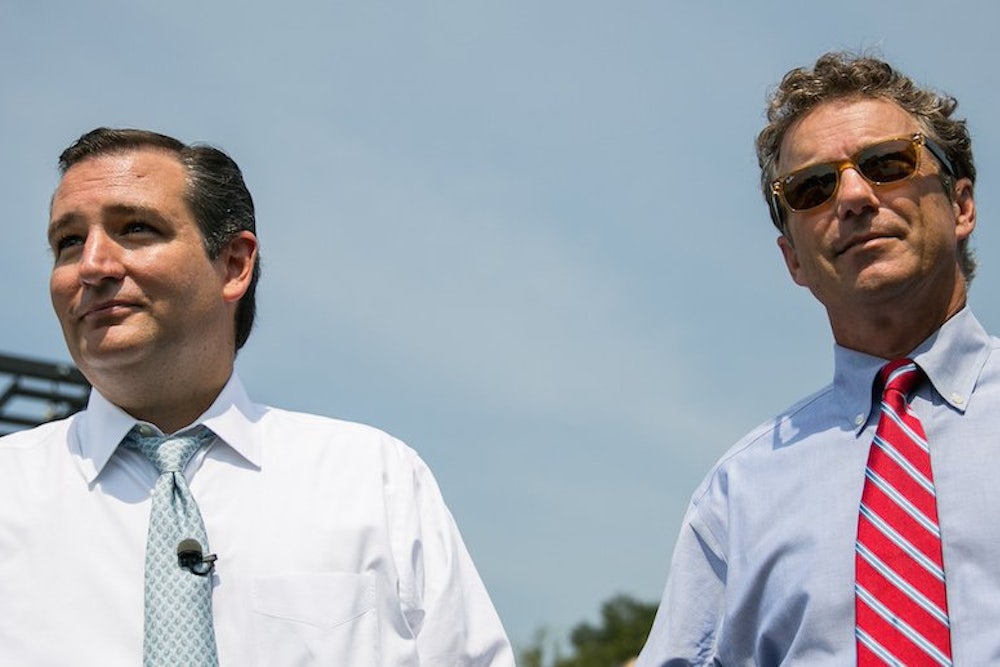

Granted, that means 39 Republican senators voted against the amendment, including two other potential 2016 candidates, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. But if nothing else, Wednesday's events show that the GOP's position on climate change is in flux. Rather than simply pretending the issue doesn't exist, as most of the 2012 candidates did, Republicans will actually debate climate change in the 2016 primary.

They still have a long way to go, including the Republicans who believe humans are responsible for global warming. What’s more important than affirming the science is whether they have a reasonable plan to address it. Paul and Romney's present and past comments, for instance, suggest they're in no hurry to take action against climate change.

Romney has adopted a number of positions on human-caused climate change in his past White House campaigns. In 2010, he said human activity was a “contributing factor” to melting ice caps. In 2011, he said he believed “humans contribute” to warming, and that we ought to reduce the pollution causing it, though he also cast doubt on “how much our contribution is.” In the 2012 primary, he swung right, arguing, “We don't know what's causing climate change on this planet." Paul, meanwhile, argued last year that the debate has been “dumbed down beyond belief” then said something scientists would find, well, dumb: “I’m not sure anybody exactly knows why” the planet is warming.

The candidates in the 2012 GOP primary not only ignored climate change, but even steered clear of traditionally conservative ideas like cap-and-trade. Jon Huntsman, the lone contender who trusted science, said his pro-climate stand "didn't help at all" when he was clobbered in the primaries. The 2016 primary is likely to be different, and not just because of Romney and Paul's moves of late. Next year's global summit in Paris could result in an international deal to cut emissions, and President Barack Obama, by using his executive authority to tighten environmental regulations, is doing everything to make climate change an unavoidable issue for the next crop of presidential contenders.

That a few prominent Republicans are staking out slightly more moderate positions proves that Obama's approach is working. The 2016 GOP primary won't feature the climate-change debate that the country needs, but it step in the right direction—away from ignorance, toward reason.