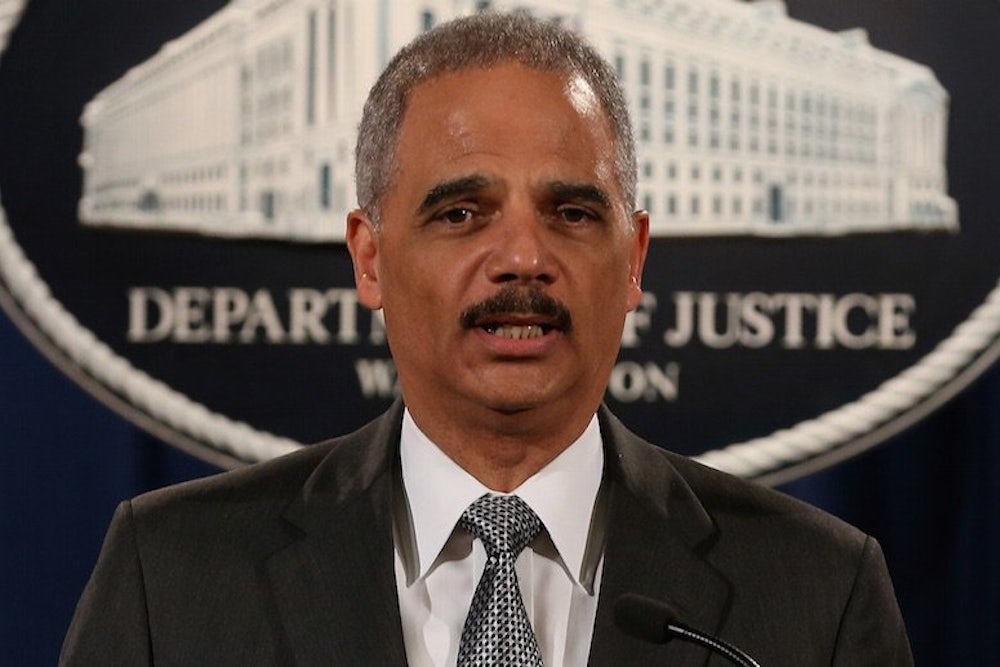

On Friday, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder announced the end to most federal “adoption” of assets taken by state and local authorities by civil forfeiture. The federal Equitable Sharing program, which delivered up to 80 percent of any seized asset’s worth directly back to the local department for supplemental revenue, provided incentive for police to aggressively seek cash and assets without having to pursue criminal charges. For thousands of police departments, Equitable Sharing worked as an end-run around state laws that restricted direct profits from asset forfeiture.

The announcement by the Department of Justice is a welcomed one. Criminal justice reformers have long called for an end to Equitable Sharing, which has been lambasted by the press and members of both parties, including members of House and Senate Judiciary Committees. But Friday's move will not put an end to the practice of civil asset forfeiture.

The federal government started the practice at the height of the drug war, in the 1980s, as a tool to combat drug trafficking. It led to a widespread abuse of power. Police seized cash and valuables from motorists, often without an arrest and without criminal charge. The assets seized under state law could then be "adopted" by the federal government, which would give the police department up to 80 percent of the assets' value back to spend on equipment, new hires, or overtime pay.

Many states followed the federal government's lead and passed legislation allowing civil forfeiture. States that already allow police keep up to 100 percent of forfeiture proceeds will be largely unaffected by the changes announced Friday. Even those police agencies that do not get direct forfeiture funds maintain the authority under many state laws to seize property without charging someone with a crime.

Current laws force the owner to prove the legitimacy of the assets seized, usually at their own cost, rather than forcing the government to prove the assets were illicit. This power turns due process on its head and should never have been allowed in the first place, regardless of its utility for fighting the drug war. As former federal officials who presided over asset forfeiture at the DOJ wrote in an op-ed for the Washington Post, “[C]ivil forfeiture is fundamentally at odds with our judicial system and notions of fairness. It is unreformable.”

In addition to the money that has been collected through Equitable Sharing, many states fail to keep track or report how much money they seize under their laws. Untold billions of dollars are taken from motorists, property owners, and small businesses to the benefit of police agencies and state budgets. So while curbing Equitable Sharing and reining in civil forfeiture has bipartisan support in Washington, state reforms will face stiff opposition from those who benefit from forfeiture the most: police organizations and budget planners.

Although departments were prohibited from using federal forfeiture funds in future budget projections, some, like the District of Columbia, have done so anyway. The coming shortfalls as a result of the new rule will put pressure on budgets of the governments who formally or informally rely on the supplemental influx of cash provided by Equitable Sharing. These shortfalls could have several unintended consequences.

As we’ve seen in New York City Police Department’s enforcement slowdown after the New Year, police provide a lot of revenue through tickets, fines, and “quality of life” summonses for petty offences. Cities and departments feeling the pinch from lost forfeiture revenue may ramp-up such enforcement, thus putting the bottom line above the common good. And since this type of enforcement often falls hardest on the poor and minorities, it can exacerbate already strained relationships between those communities and the police.

Alternatively, the exceptions to the DOJ order include assets seized by joint federal-state task forces, many of which focus on drug enforcement. This could result in more militarized raids against low-level, non-violent offenders that put lives at risk unnecessarily. Again, this enforcement is particularly felt in poor, minority neighborhoods.

Beyond the task force exception, departments could be more aggressive with criminal asset forfeiture, the seizure of property after a criminal conviction has been secured. Criminal forfeiture does not present the due process problems that civil forfeiture does, but police and prosecutors could expand its use to make up for some of the lost revenue.

It should be noted that federal civil forfeiture remains untouched. For most people, fighting federal forfeiture is prohibitively expensive and often involves seizing the very assets—cash, bank accounts, and homes—that could be used to pay the lawyers and court fees to get them back. Even if this administration curbs its use, without legislation from Congress, civil forfeiture will continue to be a potent weapon U.S. attorneys can unleash against a small businessman or farmer who runs afoul of some law or regulation. Hopefully, this one area of bipartisan agreement can produce a bill that repeals civil forfeiture for this and future administrations.

The Department of Justice did the right thing by closing the Equitable Sharing cookie jar for the more than 8,000 police agencies that have used the program. But in their zeal to fight the drug war, the federal government created regimes of state-sanctioned theft by police officers. Getting the states to end civil asset forfeiture will be a lot harder than it was getting them to adopt it.